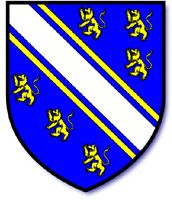

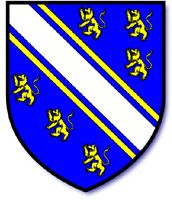

John de Lacy1

John de Lacy1

M, #2071, b. circa 1192, d. 22 July 1240

| Father* | Roger de Lacy of Pontefract2 b. c 1171, d. 1212 | |

| Mother* | Maud de Clare2 b. c 1175, d. Jan 1225 | |

John de Lacy|b. c 1192\nd. 22 Jul 1240|p70.htm#i2071|Roger de Lacy of Pontefract|b. c 1171\nd. 1212|p93.htm#i2770|Maud de Clare|b. c 1175\nd. Jan 1225|p134.htm#i4005|John d. Laci|b. 1150\nd. 11 Oct 1190|p134.htm#i4006|Alice FitzRoger|b. c 1150|p134.htm#i4007|Sir Richard de Clare|b. c 1153\nd. bt 30 Oct 1217 - 28 Nov 1217|p69.htm#i2067|Amice of Gloucester|b. c 1160\nd. 1 Jan 1224/25|p69.htm#i2068| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1192 | 1,2,3 |

| Marriage* | before 21 June 1221 | 1st=Margaret de Quincy1,2,3,4 |

| Death* | 22 July 1240 | Stanlaw, Cheshire, England, after a long illness1,3,2,5 |

| Burial* | Stanlaw Abbey, Cheshire, England, but later removed to Whalley2,5 | |

| Title | Earl of Lincoln6 | |

| Event-Misc* | July 1213 | He received his inheritance and was described as constable of Chester5 |

| Event-Misc | 1213/14 | He campaigned with King John in Poitou5 |

| (Barons) Magna Carta | 12 June 1215 | Runningmede, Surrey, England, King=John Lackland7,8,9,10,11,12 |

| Event-Misc | 1216 | King John destroyed his castle of Donington5 |

| Event-Misc | 1217 | He was pardoned by King Henry III for his opposition to King John5 |

| Event-Misc | November 1217 | He was commissioned to conduct the King of Scots to Henry III5 |

| Event-Misc | 1218 | The Battle of Damietta, Egypt, He accompanied the Earl of Chester on crusade and fought5 |

| Occupation* | 1226 | a judge5 |

| Event-Misc | 1227 | He went on a diplomatic mission to Antwerp5 |

| Event-Misc | 1229 | He conducted the King of Scots to York to meet King Henry III5 |

| Event-Misc* | 1232 | John de Lacy was the King's commissioner against Hubert de Burgh, who lost his post as Judiciar in July, Principal=Hubert de Burgh5 |

| Event-Misc | 22 November 1232 | At the insistance of his mother-in-law, King Henry III granted him the third penny of the county as Earl of Lincoln5 |

| Event-Misc | 1233 | He joined against Piers des Roches, Bishop of Winchester, but changed sides on a bribe of 1000 marks5 |

| Event-Misc | 9 December 1233 | He was given custody of the castle of Oswestry, but was subject to the King's wrath when he let Hubert de Burgh escape., Principal=Hubert de Burgh5 |

| Event-Misc | 1236 | Because of a dispute between the Earls of Chester and Warenne about who was to carry a sword, he carried it at the coronation of the Queen5 |

| Event-Misc | 1237 | "There was a great commotion among the barons when he abtained the marriage of his daughter Maud and Richard, Earl of Gloucester"13 |

| Occupation | from 1237 to 1240 | Sheriff of Chester13 |

| HTML* | Magna Charta Surety Page | |

| Title* | constable of Chester3 |

Family | Margaret de Quincy b. 1208, d. b 30 Mar 1266 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 8 Jun 2005 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 38.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 54-29.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 107-3.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 121.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 59.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Longespée 3.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Warenne 3.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 56-27.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 60-28.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 8.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 34.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 122.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 107-4.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Clare 11.

- [S285] Leo van de Pas, 30 Jun 2004.

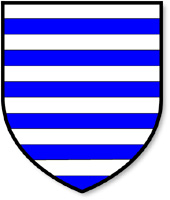

Margaret de Quincy1

F, #2072, b. 1208, d. before 30 March 1266

| Father* | Sir Robert de Quincey2,3,4,5,6 | |

| Mother* | Hawise of Chester (?)3,5 b. 1180, d. bt 6 Jun 1241 - 3 Mar 1243 | |

Margaret de Quincy|b. 1208\nd. b 30 Mar 1266|p70.htm#i2072|Sir Robert de Quincey||p70.htm#i2073|Hawise of Chester (?)|b. 1180\nd. bt 6 Jun 1241 - 3 Mar 1243|p228.htm#i6832|Saher I. de Quincy|b. c 1155\nd. 3 Nov 1219|p69.htm#i2046|Margaret de Beaumont|b. c 1155\nd. 12 Jan 1234/35|p69.htm#i2047|Hugh of Kevelioc|b. 1147\nd. 30 Jun 1181|p59.htm#i1758|Bertrade de Montfort|b. 1155\nd. 1227|p97.htm#i2903| | ||

| Birth* | 1208 | Lincolnshire, England3 |

| Marriage* | before 21 June 1221 | 2nd=John de Lacy2,3,1,5 |

| Marriage* | before 20 April 1242 | Groom=Sir Walter Marshal7 |

| Marriage* | before 7 June 1252 | Groom=Richard de Wiltshire7 |

| Death* | before 30 March 1266 | Clerkenwell, Middlesex, England2,3,5 |

| Burial* | Church of the Hospitallers, Clerkenwell, Middlesex, England7 | |

| Name Variation | Margaret de Quincey2 |

Family | John de Lacy b. c 1192, d. 22 Jul 1240 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 8 Jun 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 54-29.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 38.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 54-28.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 107-3.

- [S285] Leo van de Pas, 30 Jun 2004.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 121.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 107-4.

Sir Robert de Quincey1

Sir Robert de Quincey1

M, #2073

|

| Father* | Saher IV de Quincy2,3,4 b. c 1155, d. 3 Nov 1219 | |

| Mother* | Margaret de Beaumont2,3 b. c 1155, d. 12 Jan 1234/35 | |

Sir Robert de Quincey||p70.htm#i2073|Saher IV de Quincy|b. c 1155\nd. 3 Nov 1219|p69.htm#i2046|Margaret de Beaumont|b. c 1155\nd. 12 Jan 1234/35|p69.htm#i2047|Robert de Quincey|d. c 1198|p92.htm#i2746|Orabella of Leuchars|d. b 30 Jun 1203|p92.htm#i2747|Sir Robert de Beaumont|b. b 1135\nd. 31 Aug 1190|p365.htm#i10927|Petronilla de Grandmesnil|b. 1149\nd. 1 Apr 1212|p92.htm#i2749| | ||

| Marriage* | 2nd=Hawise of Chester (?)2,3,5,6 | |

| Marriage | between 6 June 1237 and 5 December 1237 | 2nd=Helen ferch Llywelyn ab Iorwerth2,7 |

| Burial* | Church of the Hospitallers, Clerkenwell, Middlesex, England8 | |

| Note* | Boyer says his mother is not known to be Margaret9 | |

| Name Variation | Sir Robert de Quincy2,7 | |

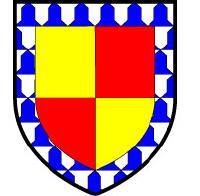

| Arms | De goules ung quintefueile de hermyne (Glover). Gu. a cinquefoil pierce arg.4 | |

| Occupation* | a crusader5 | |

| Event-Misc | 4 September 1264 | Inquest was held whether reversion to his heirs should occur re property he granted to Roger de Quency, Earl of Winchester, and his heirs male corp., Stiventon Manor, with reversion to himself and heirs.4 |

Family 1 | Hawise of Chester (?) b. 1180, d. bt 6 Jun 1241 - 3 Mar 1243 | |

| Child |

| |

Family 2 | Helen ferch Llywelyn ab Iorwerth d. 25 Nov 1253 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 3 Aug 2005 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 38.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 54-28.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 107.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 107-2.

- [S285] Leo van de Pas, 30 Jun 2004.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Wales 5.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 121.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 211.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 107-3.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Bohun 6.

Joan of Acre1

F, #2074, b. Spring 1272, d. 23 April 1307

| Father* | Edward I "Longshanks" Plantagenet King of England1,2,3,4,5 b. 17 or 18 Jun 1239, d. 7 Jul 1307 | |

| Mother* | Eleanor of Castile6,2,4,5 b. 1240, d. 28 Nov 1290 | |

Joan of Acre|b. Spring 1272\nd. 23 Apr 1307|p70.htm#i2074|Edward I "Longshanks" Plantagenet King of England|b. 17 or 18 Jun 1239\nd. 7 Jul 1307|p54.htm#i1614|Eleanor of Castile|b. 1240\nd. 28 Nov 1290|p54.htm#i1615|Henry I. Plantagenet King of England|b. 1 Oct 1207\nd. 16 Nov 1272|p54.htm#i1618|Eleanor of Provence|b. 1217\nd. 24 Jun 1291|p54.htm#i1619|Fernando I. of Castile "the Saint"|b. bt 5 Aug 1201 - 19 Aug 1201\nd. 30 May 1252|p95.htm#i2832|Joan de Dammartin|b. c 1218\nd. 16 Mar 1279|p95.htm#i2833| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | Spring 1272 | Acre, Palestine1,2,7 |

| Marriage* | circa 30 April 1290 | Westminster Abbey, Westminster, Middlesex, England, 2nd=Sir Gilbert de Clare "the Red"1,8,2,3,9,10 |

| Marriage* | January 1297 | clandestinely, Groom=Sir Ralph de Monthermer2,11,9,10 |

| Death* | 23 April 1307 | Clare, Suffolk, England1,8,2,12,9 |

| Burial* | Augustina Priory, Clare, Suffolk, England2 | |

| DNB* | Joan [Joan of Acre], countess of Hertford and Gloucester (1272-1307), princess, the second surviving daughter of Edward I (1239-1307) and Eleanor of Castile (1241-1290), was born at Acre early in 1272 during her father's crusade. The future Edward II was her brother, and Mary (1278-c.1332) was her sister. She was brought up in Ponthieu by her grandmother Jeanne de Dammartin, widow of Ferdinand III of Castile, until 1278 when Stephen of Penecester and his wife were sent by Edward I to bring her to England. Edward I had begun negotiations the year before with Rudolf of Habsburg, king of the Romans, for Joan's marriage to his eldest son, Hartman; Rudolf promised to try to secure Hartman's election as king of the Romans and of Arles. Although plans were made for the celebration of the marriage in 1278, it was in fact put off, and Hartman was drowned in an accident on the ice in 1282. The agreement for Joan's marriage to Gilbert de Clare, earl of Hertford and Gloucester, was made in 1283. Gilbert and his first wife, Alice de la Marche, had had only two daughters; this marriage was dissolved in 1285, and a papal dispensation for the marriage to Joan was obtained four years later. Gilbert surrendered all his lands to the king, and they were settled jointly on Gilbert and Joan for their lives, and were then to pass to their children; if however the marriage was childless, the lands were to pass to Joan's children by any later marriage. The wedding took place at Westminster on 30 April 1290. Shortly afterwards both Gilbert and Joan took the cross, but neither went on crusade. They had one son, Gilbert de Clare, who was born in May 1291, to the great joy of both parents, and three daughters, among them Elizabeth de Clare and Margaret de Clare. In 1294 Gilbert and Joan and their children were driven out of the Clare lordship of Glamorgan by the Welsh rebellion, and Gilbert died on 7 December 1295. Because of the joint enfeoffment of Gilbert and Joan, the widowed countess remained in charge of the estates, performing homage to her father on 20 January 1296. The estates included lands in Ireland and Wales as well as the honours of Clare and Gloucester and other manors in England, and produced a yearly income of about £6000 in the early fourteenth century. Edward I planned for Joan to marry Amadeus V of Savoy, and the betrothal document was dated 16 March 1297. However by then Joan had secretly married a squire of Earl Gilbert's household, Ralph de Monthermer, whom she had persuaded her father to knight. She is reputed to have said, ‘It is not ignominious or shameful for a great and powerful earl to marry a poor and weak woman; in the reverse case it is neither reprehensible or difficult for a countess to promote a vigorous young man’ (Trokelowe and Blaneforde, 27). Monthermer was imprisoned for a short time in Bristol Castle, but performed homage on 2 August 1297, and the Clare estates were restored to him and Joan (although Tonbridge and Portland were not restored until 1301). Monthermer enjoyed the title of earl of Hertford and Gloucester during his wife's lifetime. He and Joan had two sons and a daughter. Joan died at Clare, Suffolk, on 23 April 1307, and was buried in the church of the Augustinian friars there; she had made benefactions to the priory and built the Chapel of St Vincent. Jennifer C. Ward Sources Rymer, Foedera, vol. 1 · Ann. mon. · A. Gransden, ed. and trans., The chronicle of Bury St Edmunds, 1212–1301 [1964] · Bartholomaei de Cotton … Historia Anglicana, ed. H. R. Luard, Rolls Series, 16 (1859) · The chronicle of Walter of Guisborough, ed. H. Rothwell, CS, 3rd ser., 89 (1957) · H. R. Luard, ed., Flores historiarum, 3 vols., Rolls Series, 95 (1890) · [W. Rishanger], The chronicle of William de Rishanger, of the barons' wars, ed. J. O. Halliwell, CS, 15 (1840) · Chronica Johannis de Oxenedes, ed. H. Ellis, Rolls Series, 13 (1859) · Johannis de Trokelowe et Henrici de Blaneforde … chronica et annales, ed. H. T. Riley, pt 3 of Chronica monasterii S. Albani, Rolls Series, 28 (1866) · M. Altschul, A baronial family in medieval England: the Clares, 1217–1314 (1965) · M. A. E. Green, Lives of the princesses of England, 2 (1849) · J. C. Parsons, ed., The court and household of Eleanor of Castile in 1290, Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies: Texts and Studies, 37 (1977) Archives BL · PRO © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Jennifer C. Ward, ‘Joan , countess of Hertford and Gloucester (1272-1307)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/14821, accessed 23 Sept 2005] Joan (1272-1307): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1482113 | |

| Name Variation | Plantagenet8 |

Family 1 | Sir Gilbert de Clare "the Red" b. 2 Sep 1243, d. 7 Dec 1295 | |

| Children |

| |

Family 2 | Sir Ralph de Monthermer b. 1262, d. 5 Apr 1325 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 23 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 38.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-4.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 14.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 5.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8-28.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Lancaster 5.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8-29.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Clare 11.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Montagu 6.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 17B-15.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 28-4.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 207.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 9-29.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 13-6.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Montagu 7.

Sir Roger Bigod1

M, #2075, b. before 1140, d. before 2 August 1221

|

| Father* | Hugh Bigod2 b. c 1095, d. b 6 Mar 1176/77 | |

| Mother* | Juliana de Vere2 b. c 1116 | |

Sir Roger Bigod|b. b 1140\nd. b 2 Aug 1221|p70.htm#i2075|Hugh Bigod|b. c 1095\nd. b 6 Mar 1176/77|p116.htm#i3469|Juliana de Vere|b. c 1116|p116.htm#i3470|Roger Bigod|b. c 1050\nd. 8 Sep 1107|p140.htm#i4195|Adeliza de Tony|b. c 1069|p140.htm#i4196|Aubrey de Vere|b. b 1090\nd. 15 May 1141|p380.htm#i11371|Adeliza de Clare|b. c 1118\nd. c 1163|p117.htm#i3501| | ||

| Birth* | before 1140 | 3 |

| Birth | circa 1150 | 1,2,4 |

| Marriage* | before 1190 | Principal=Ida de Tony1,5 |

| Death* | before 2 August 1221 | 1,2,4 |

| DNB* | Bigod, Roger (II), second earl of Norfolk (c.1143-1221), magnate, was the only son of Hugh (I) Bigod, earl of Norfolk (d. 1176/7), and his first wife, Juliana (d. 1199/1200), sister of Aubrey (III) de Vere, earl of Oxford. After repudiating his first wife, Hugh married Gundreda (d. 1206×8), daughter of Earl Roger of Warwick, and with her had two further sons, Hugh (d. c.1203) and William. Roger (II) Bigod married Ida, of unknown parentage, with whom he had four sons, Hugh (II) (d. 1225), William, Ralph, and Roger, and two daughters, Mary, who married Ralph fitz Robert, and Margery, who married William of Hastings. The accession of Roger (II) Bigod to his father's estates provides a stunning example of how a medieval king could profit from family squabbles among his higher aristocracy. When Hugh Bigod repudiated his first wife in favour of Gundreda and then produced two more sons with his name, he brought upon his first son a dispute over the inheritance which would muddy the waters for over twenty years after his death. No sooner had Hugh been placed in the ground at Thetford Priory, than Gundreda, like the wicked stepmother of legend, asserted the claim of her first son by Hugh, confusingly also named Hugh, to certain of her late husband's estates which, she claimed, had been acquired during his lifetime and which he had bequeathed to Hugh as was his right. Never a man to miss an opportunity to keep his barons in check, Henry II took possession of large parts of Bigod land in Norfolk and refused to recognize Roger's claim to the earldom, which his father seems to have lost in 1174. The roots of this antipathy towards the Bigod family go back to Hugh's participation in the revolt of 1173–4 against Henry II, which resulted in the destruction of Framlingham Castle, seemingly the Bigod caput, and the lasting enmity of the king. When Hugh died in 1176 or 1177 and Gundreda pushed her son's claims to part of the Bigod inheritance, Henry II felt no compunction in making Roger (who was by this time already of age) feel extremely uncomfortable by allowing the case to continue unresolved, refusing to allow him the earldom of Norfolk, and confiscating these disputed lands. It is a true testament to the fear that a powerful magnate like the earl of Norfolk could engender in a twelfth-century king that, despite the fact that Roger himself had remained faithful during the rebellion of 1173–4 and can be found in the king's service before 1176, Henry II still felt the need to take advantage of Roger's little local difficulty to hold him in check. The saga of the claims of Gundreda and Hugh to a part of Roger's inheritance was to dog the earl until 1199. There was one light on the horizon, however. The accession of Richard I in 1189 brought Roger (II) back into royal favour. The new king bestowed upon Roger the long-awaited earldom of Norfolk for the relatively paltry sum of 1000 marks. From that moment on circumstances improved for the newly belted earl. He can be found with the king on a regular basis before Richard embarked on crusade, and he supported the interim government throughout the difficult years of the king's absence. It seems that Roger (II) also had a part to play in Richard's release from captivity and was in Germany when Richard's freedom was secured. At Richard's second coronation in 1194 Bigod was one of four earls given the privilege of carrying the silken canopy that covered the king. He was a baron of the exchequer between 1194 and 1196, and also served as a justice on eyre and coram rege during Richard's reign. And he had the hereditary stewardship of the royal household returned to him. Roger (II) also found time to serve in Richard's armies on the continent. The conclusion of more than twenty years' squabbling with his half-brother, Hugh, in 1199 for a settlement of an estate held of the earl, worth a scant £30, merely served to set the seal on a thoroughly successful reign for Bigod. It was at this point, also, that Bigod set about rebuilding Framlingham Castle, much improved from the structure destroyed in 1176, in stone and in the ‘new fashion’. The castle as it stands today is mostly from this date. The story of a successful and loyal king's earl continued well into the next reign. Bigod was present at John's coronation on 27 May 1199, and was dispatched thence to the king of Scots, to bring him to John for the performance of homage. He seems to have executed his military duties to John in Normandy and was one of the earls who was in constant attendance upon the king. He went to Poitou in 1206 and can be found on the royal campaigns in Scotland (1209), Ireland (1210), and Wales (1211). Despite this record of service Earl Roger joined the rebel side in the civil war that marked the end of King John's reign. Financial pressure may have been a reason. The scutage due on some 160 knights' fees, which the earl came to hold by the end of his life, was liable to be heavy, so much so that in 1211 Bigod struck a bargain with the king to pay 2000 marks (£1333 6s. 8d.) for respite during his lifetime from demands for arrears, and for being allowed to pay scutage on only 60 fees in future. He was pardoned 360 marks of this debt, but paid the substantial sum of 1340 marks in 1211 and 1212. Nor was this the only way in which John showed himself less than favourable towards the earl. In 1207 one William the Falconer brought an action against Bigod at Westminster, but when the earl objected to the chosen jurors on the grounds of their likely bias, his arguments were ignored by the king, who ordered that the case proceed. Both Earl Roger (now probably over seventy) and his son, Hugh Bigod (d. 1225), were later named as being among the committee of twenty-five set up by Magna Carta to control the king, for which they were both declared excommunicate by Pope Innocent III (r. 1198–1216) in December of that year. John's irritation at Bigod's defection and the subsequent events illustrate clearly how the king intended to bring his magnates to heel. After a lightning campaign in the north, during which he effectively reduced his opponents there to submission, John returned to East Anglia, also a centre of resistance. Judging from John's actions in March 1216, Earl Roger was the linchpin in this resistance to the king. Framlingham Castle was quickly invested, and equally quickly taken. The king then sent letters of safe conduct to Bigod in an attempt to bring him into line. Meanwhile John systematically stripped the earl of his followers in the area by pardoning those captured and returning to them seisin of their properties, while declaring those who refused to submit disseised of their lands. But, despite these tactics, Roger and Hugh Bigod remained in rebellion, and indeed did not return to the loyalist fold until after the peace of Kingston (though before the peace of Lambeth) in September 1217. By April 1218 Bigod had received back all his lands and titles and withdrawn into semi-retirement, rarely appearing in the royal records before his death some time before 2 August 1221. He was succeeded as earl by his son Hugh (II) Bigod, who was of age at the time of his father's death, and who in 1206 or 1207 married Matilda, daughter of William (I) Marshal (d. 1219). Their children included Roger (III) Bigod, earl of Norfolk, and Hugh (III) Bigod, the baronial justiciar. Earl Roger (II) Bigod made a number of religious benefactions during his long life. He continued the family tradition of patronizing Earls Colne Priory, Essex, and the abbeys of Wymondham, Norfolk, and Rochester, Kent. He made grants to monasteries at Bungay, Suffolk, Carrow, Norfolk, Hickling, Norfolk, Leiston, Suffolk, and Sibton, Suffolk, as well as to the two cells of Rochester at Felixstowe, Suffolk, and at Harwich, Essex. All these grants mark him as a conventionally pious man of his age. Roger (II)'s period as earl of Norfolk was clearly a success, notwithstanding his being on the wrong side in the civil war against King John. His father, Hugh (I), had ended his life in disgrace and bequeathed a legacy to Earl Roger of Henry II's enmity and an inheritance dispute. By the time that Earl Roger himself died, the Bigod lands were secured and indeed probably expanded. Framlingham Castle was rebuilt, and, despite falling to the king's forces in March 1216, it did not suffer the same fate as its predecessor but remained the family caput until the eventual demise of the family in 1306. Moreover, Earl Roger left his son an undisputed inheritance. S. D. Church Sources S. A. J. Atkin, ‘The Bigod family: an investigation into their lands and activities, 1066–1306’, PhD diss., U. Reading, 1979 · R. A. Brown, ‘Framlingham Castle and Bigod, 1154–1216’, Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology, 25 (1951), 127–48; repr. in R. A. Brown, Castles, conquest and charters: collected papers (1889), 187–208 · Pipe rolls, 13–14, 16 John; 2 Henry III · R. V. Turner, The king and his courts (1968), 108 · W. Stubbs, ed., Select charters and other illustrations of English constitutional history, 9th edn (1913), 164 [repr. with corrections, ed. H. W. C. Davis (1921)] Wealth at death £162 3s. 4d.—knights' fees in Norfolk and Suffolk: Atkin, ‘The Bigod family’, 178; Pipe rolls, 13–14, 16 John, 177 © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press S. D. Church, ‘Bigod, Roger (II), second earl of Norfolk (c.1143-1221)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/2379, accessed 24 Sept 2005] Roger (II) Bigod (c.1143-1221): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23796 | |

| Event-Misc | January 1163/64 | He attended the Council of Clarendon7 |

| Event-Misc | October 1171 | Pembroke, He was with the King7 |

| Event-Misc | 1172 | Battle of Fornham, He opposed his father, bearing the Royal Standard7,5 |

| Event-Misc | 1176 | Roger Bigod and his stepmother Gundred (on behalf of her son) disputed his inheritance to King Henry II, who took the lands into his own hands, but allowed titular succession to Roger, Principal=Gundred de Warenne5 |

| Event-Misc | 1182 | His father's fine was forgiven him and his father's lands restored to him7 |

| Title* | 1186 | Royal Steward8 |

| Title | 27 Nov 1 Richard I | He was confirmed by the King as Earl of Norfolk and Steward of the Royal Household9,10 |

| Event-Misc | 1189 | He was ambassador from Richard I to Philip King of France to help arrange Richard's crusade10,5 |

| Event-Misc | between 1189 and 1193 | He granted 3 marks of rent in Walton, Norfolk to Reading Abbey for the health of his sould and that of his wife, Ida5 |

| Event-Misc | 1191 | He was granted Hereford Castle5 |

| Event-Misc | 1191 | He supported the chancellor against Prince John while King Richard was away on crusade.7 |

| Event-Misc | 1193 | He went to Germany to ransom Richard7,5 |

| Note* | 17 April 1194 | On King Richard's return after his captivity, the Earl assisted at the great council at Nottingham. He was one of the four earls carrying the silken canopy over Richard's head at his 2nd Coronation.10,7 |

| Title | between 1195 and 1196 | Baron of the Exchequer8 |

| (Witness) Crowned | 27 May 1199 | Westminster Abbey, Westminster, Middlesex, England, King of England, Principal=John Lackland11,12,13,14,7,15 |

| Event-Misc | November 1200 | He was sent to Scotland to bring the Scottish King to Lincoln to do homage to John7,5 |

| Event-Misc | May 1212 | Lambeth, He witnessed King John's charter to the Count of Boulogne after his homage7 |

| Event-Misc | 1213 | He was imprisoned for unknown causes5 |

| Event-Misc | 1214 | He was with the King in Poitou5 |

| (Barons) Magna Carta | 12 June 1215 | Runningmede, Surrey, England, King=John Lackland16,17,18,19,20,21 |

| Excommunication* | 16 December 1215 | by the Pope7,5 |

| Event-Misc* | September 1217 | His lands were returned to him following John's death7,5 |

Family | Ida de Tony | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 38.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S374] Douglas Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry, Bigod 3.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 3-1.

- [S374] Douglas Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry, Bigod 1.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 29.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 155-2.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 92.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 53.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 1-26.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 16.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Warenne 2.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 3.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 84.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Longespée 3.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Warenne 3.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 56-27.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 60-28.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 8.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 34.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 7-2.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 30.

Ida de Tony1

F, #2076

| Father* | Ralph V de Tony1 d. 1162 | |

Ida de Tony||p70.htm#i2076|Ralph V de Tony|d. 1162|p209.htm#i6268||||Roger I. de Tony|b. c 1104\nd. a 29 Sep 1158|p209.htm#i6270|Ida of Hainault||p210.htm#i6271||||||| | ||

| Of* | Sussex, England2 | |

| Mistress* | Principal=Henry II Curtmantel1 | |

| Marriage* | before 1190 | Principal=Sir Roger Bigod3,1 |

Family 1 | Sir Roger Bigod b. b 1140, d. b 2 Aug 1221 | |

| Children |

| |

Family 2 | Henry II Curtmantel b. 5 Mar 1132/33, d. 6 Jul 1189 | |

| Child |

| |

Family 3 | Ralph Bigod b. c 1184 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 10 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S374] Douglas Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry, Bigod 1.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 38.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 53.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 30.

- [S285] Leo van de Pas, 30 Jun 2004.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 164-2.

Sir Hamelin Plantagenet1,2

M, #2077, b. circa 1130, d. 7 May 1202

| Father* | Geoffrey V "the Fair" Plantagenet1,3 b. 24 Nov 1113, d. 7 Sep 1151 | |

| Mother* | Anonyma (?)3 | |

Sir Hamelin Plantagenet|b. c 1130\nd. 7 May 1202|p70.htm#i2077|Geoffrey V "the Fair" Plantagenet|b. 24 Nov 1113\nd. 7 Sep 1151|p55.htm#i1624|Anonyma (?)||p457.htm#i13698|Fulk V. of Anjou "the Young"|b. 1092\nd. 10 Nov 1143|p97.htm#i2898|Erembourg of Maine|d. 1126|p97.htm#i2899||||||| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1130 | Normandy, France4 |

| Marriage* | April 1164 | 2nd=Isabel de Warene1,4,5 |

| Death* | 7 May 1202 | Lewes, Sussex, England1,4,5 |

| Burial* | Lewes Priory Chapter House, Lewes, Sussex, England4,5 | |

| DNB* | Warenne, Hamelin de, earl of Surrey [Earl Warenne] (d. 1202), magnate, was the natural son of Geoffrey, count of Anjou (d. 1151), and half-brother of Henry II, from whom he received the Warenne Anglo-Norman honours with the title earl of Surrey in April 1164 on his marriage to Isabel de Warenne, countess of Surrey (d. 1203), widow of William of Blois, Earl Warenne (d. 1159). Although Hamelin readily adopted the Warenne family name, he proudly acknowledged in his charters both his Angevin paternal heritage and his debt to his royal brother. Hamelin's first reported political act, a vociferous denunciation of Thomas Becket at the Council of Northampton in October 1164, was motivated by the archbishop's perceived injury to the royal family in blocking the marriage of William FitzEmpress to the Countess Isabel on grounds of consanguinity. William had died shortly thereafter while seeking the intervention of his mother, the Empress Matilda, in the matter. Many of his friends believed that the disappointment had helped to cause his death. Few at court could have missed the connection, psychological or otherwise, of Hamelin's good fortune in gaining his title and high-born wife with the equally great misfortune of the death of the king's (and Hamelin's) younger brother. It is within this context that Hamelin's early confrontational attitude towards Thomas Becket is best explained. Years later the earl became, as did Henry II himself, an active participant in the then sainted archbishop's cult, having been healed, miraculously it was thought, of a cataract in one eye by the covering which lay on Becket's tomb. In England in 1166, and again in Normandy in 1172, Hamelin was one of a handful of élite Anglo-Norman courtiers who were not obligated to report their knights' fees and their royal or ducal knight service. Consequently the Warenne fiefs are missing from the great surveys of Henry II's reign: the Cartae baronum and the Infeudationes militum. None the less, other near-contemporary sources indicate something of the magnitude and importance of the Warenne honours. The Domesday evaluation of the family's lands in England amounted to some £1140, which placed them among the four or five wealthiest secular holdings below the king. By the second half of the twelfth century over 140 knights' fees had been subinfeudated by the Warennes, making Hamelin in 1173 the ninth greatest lord in England as reckoned by enfeoffments. What his ranking may have been in Normandy is difficult to say, except that his wife's ancestral lands, centred on the strategic castles of Mortemer and Bellencombre, would have made the earl a major force in Upper Normandy. Indeed castles are as good a measure as any other of power, prestige, and wealth. On the English side of the channel Hamelin inherited castles at Lewes, Castle Acre, Reigate, and Sandal. For his part he built (c.1180) the magnificent keep at Conisbrough, which was later to serve as an inspiration for Sir Walter Scott's Ivanhoe. Hamelin was well connected politically outside the royal family. His brother-in-law, Reginald de Warenne, worked frequently as a baron of the English exchequer. Hugh de Cressy, a Warenne under-tenant and sometime seneschal, rose to become Henry II's constable for Rouen and constant companion. Like so many of his peers Hamelin enjoyed prestige and wealth without much interference from royal government. According to the English pipe rolls the earl was assessed a total of £276 over a period of thirty-eight years, against which he paid the sum of £74, mostly on scutages taken from his under-tenants. It would be wrong to conclude from this, however, that Hamelin lived the pampered life of a detached aristocrat. His wealth and connections did obligate him to an active participation in state affairs, an obligation he took seriously. Throughout his tenure as earl, Hamelin remained steadfastly loyal to his brother the king, to his nephew Richard I, and, when challenged, to Angevin royal interests. Judging from the relatively low number of royal charters attested by Hamelin (ten), the earl apparently never entered the intimate, inner circle at Henry II's court, as did other family members like Reginald, earl of Cornwall. And yet, at critical moments in the reign, he is found at his brother's side. When Henry met Raymond de St Gilles, count of Toulouse, in February 1173 at Fontevrault to settle long-standing differences, Hamelin was there attesting charters as ‘vicomte of the Touraine’. That Henry chose the earl to act as vicomte in this sensitive border region between the houses of Anjou and Blois displays great trust. Perhaps Hamelin took up this office during the king's stay in Ireland (1171–2), when the hostility of the French court, particularly the Blois family, was directed against the Angevin monarchy for Henry's perceived complicity in the murder of Thomas Becket. If so, Hamelin acted as one of the chief protectors of his brother's dominions during the time of Henry's self-imposed Irish exile. Equally important, the political manoeuvrings of February 1173 saw the king negotiating a marriage for John to the daughter of the count of Maurienne and fending off the demand of Henry, the Young King, to be put in control of some part of his inheritance. Henry's announced intention of the conveyance of the Tourangeaux castles of Chinon and Loudun to the five-year-old John as a marriage portion precipitated the premature launching by Henry, the Young King, of the rebellion he had been planning against his father. Lost in subsequent events is the fact that Hamelin would have been the local overseer of John's properties had the original plan been carried out. Hamelin held fast with his brother against his nephews and their French and Scottish allies in the ensuing civil war and next appears in the chronicles in 1176 as a member of Joan's escort through central and southern France as his niece, the princess, journeyed to Sicily for her marriage with King William. In the 1180s Hamelin focused much of his energy on his estates in Yorkshire, building the wondrous castle and keep at Conisbrough. He undoubtedly spent more time in Yorkshire than any of the other Warenne earls and may have been attracted to the region as much by the opportunity to leave his own fresh mark in a family of prodigious builders as by the thriving northern economy. Years of experience at the Angevin court, coupled with private success in the management of the diverse Warenne properties, earned Hamelin a respect which would serve him well in the troubled years following Henry II's death in 1189. Although Hamelin played no ceremonial role in Richard I's first coronation, as did other earls, he travelled widely with the new king, attesting thirteen charters, at Geddington (three), Bury St Edmunds (three), Canterbury (three), Rouen (three), and Montrichard (one), all before July 1190, when the main Angevin armies departed on crusade. With Richard gone Hamelin quickly attached himself to the king's chancellor, William de Longchamp, bishop of Ely. Their friendship was born of necessity: Longchamp was attempting to whittle down the power in the north of Hugh du Puiset, bishop of Durham, while fending off the intrigues of the king's brother, Count John; and Hamelin was equally disturbed by Hugh and John, holding true to the monarchy and his nephew, the king, as he had to his brother. Hamelin felt most comfortable adhering to the law (the legend on his seal reads ‘pro lege, per lege’) and, with Richard gone, William de Longchamp represented the law. When Geoffrey, archbishop of York (yet another nephew), was taken into custody at Dover in September 1191, when he attempted to enter England contrary to royal order, it was Earl Hamelin who was dispatched by the chancellor to bring the archbishop to London to face judgment by the ‘barons of the realm’. When the outrage over the archbishop's treatment, combined with a growing sense of Longchamp's unrestrained ambition, allowed Count John to galvanize baronial discontent for a showdown with the chancellor at Loddon Bridge near Windsor in October, Hamelin again was conspicuous in his support of Longchamp. And after the chancellor's exile, when news of Richard's captivity in Germany reached England, Hamelin acted as one of only two magnates (William d'Aubigny, earl of Arundel, being the other) who were entrusted with the collection and safe keeping of the king's ransom. After Richard's return in 1194 the earl took a place of honour at a second coronation, carrying one of the three swords of state with William, king of Scots, and Ranulf (III), earl of Chester. A northern orientation again is apparent in these pairings. At the Council of Nottingham that same year Hamelin sat with Richard as sentences were handed out to John's followers and other disturbers of the king's peace. With this, Hamelin's long involvement in national politics slowed to an end. Present at John's coronation in May 1199, the earl attested no royal charters from the reign, though he is reported by Roger of Howden to have witnessed an oath given by William, king of Scots in November 1200. Absorbed by private matters, most notably a dispute with Cluny over the right to appoint the prior of Lewes, Earl Hamelin died on 7 May 1202 and was buried in the chapter house at St Pancras Priory, Lewes, Sussex. The Countess Isabel died shortly thereafter and was interred with her husband. The earl and countess were survived by four children: William (IV) de Warenne, who succeeded to the earldom; Isabel, who married first Robert de Lacy of Pontefract and second Gilbert de l'Aigle of Pevensey; Maud, who married first Henry, count of Eu, and second Henry de Stuteville, lord of Valmont in Normandy; and Ela, who married first Robert of Naburn and second William fitz William of Sprotborough. If many of the personal details of Earl Hamelin's life are unknown, something of his mind comes through in these words taken from a grant to Lewes: ‘grounds for forgetfulness and dispute are wont to be removed by the good effect of a written deed’ (Cartulary of the Priory of St Pancras of Lewes, 1932–3, 38.45). In his heart, then, the earl was both lawyer and historian. Thomas K. Keefe Sources R. Howlett, ed., Chronicles of the reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I, 4, Rolls Series, 82 (1889) · J. C. Robertson and J. B. Sheppard, eds., Materials for the history of Thomas Becket, archbishop of Canterbury, 7 vols., Rolls Series, 67 (1875–85) · W. Stubbs, ed., Gesta regis Henrici secundi Benedicti abbatis: the chronicle of the reigns of Henry II and Richard I, AD 1169–1192, 2 vols., Rolls Series, 49 (1867) · Ralph de Diceto, ‘Ymagines historiarum’, Radulfi de Diceto … opera historica, ed. W. Stubbs, 2 vols., Rolls Series, 68 (1876) · Chronica magistri Rogeri de Hovedene, ed. W. Stubbs, 4 vols., Rolls Series, 51 (1868–71) · W. Stubbs, ed., Chronicles and memorials of the reign of Richard I, 2: Epistolae Cantuarienses, Rolls Series, 38 (1865) · Gir. Camb. opera · Chronicon Richardi Divisensis / The Chronicle of Richard of Devizes, ed. J. T. Appleby (1963) · C. T. Clay, ed., The honour of Warenne (1949), vol. 8 of Early Yorkshire charters, ed. W. Farrer and others (1914–65) · W. Farrer, Honors and knights' fees … from the eleventh to the fourteenth century, 3 (1925) · T. K. Keefe, Feudal assessments and the political community under King Henry II and his sons (1983) · H. M. Thomas, Vassals, heiresses, crusaders, and thugs: the gentry of Angevin Yorkshire, 1154–1216 (1993) · J. T. Appleby, England without Richard, 1189–1199 (1965) © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Thomas K. Keefe, ‘Warenne, Hamelin de, earl of Surrey (d. 1202)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/28732, accessed 24 Sept 2005] Hamelin de Warenne (d. 1202): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/287326 | |

| Name Variation | Hameline Plantagenet7 | |

| Event-Misc* | 1164 | He was present at the Council of Northampton and joined in the denunciation of Thomas-a-Becket5 |

| Event-Misc | 1174 | He supported Henry II against his sons5 |

| Event-Misc | 1176 | He escorted Joan, daughter of King Henry II for her marriage to the King of Sicily, Witness=Joan of England5 |

| (Witness) King-England | 3 September 1189 | Westminster, Middlesex, England, Principal=Richard I the Lionhearted5,8,9,10 |

| Event-Misc | 1193 | He bore one of the three swords at the 2nd coronation of Richard I5 |

| Event-Misc | 1193 | He was one of the treasurers for the ransom of King Richard I5 |

| (Witness) Crowned | 27 May 1199 | Westminster Abbey, Westminster, Middlesex, England, King of England, Principal=John Lackland11,12,5,9,13,14 |

Family | Isabel de Warene b. c 1137, d. 12 Jul 1203 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 83-26.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Bohun 3.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 1.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Warenne 2.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 38.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 2.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 3.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 79.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 1-26.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 16.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 29.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 84.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-27.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 123-27.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 151-1.

Isabel Bigod1

F, #2078, b. circa 1210

| Father* | Sir Hugh Bigod2,4,5 d. bt 11 Feb 1225 - 18 Feb 1225 | |

| Mother* | Maud Marshal2,3 b. c 1192, d. 27 Mar 1248 | |

Isabel Bigod|b. c 1210|p70.htm#i2078|Sir Hugh Bigod|d. bt 11 Feb 1225 - 18 Feb 1225|p90.htm#i2672|Maud Marshal|b. c 1192\nd. 27 Mar 1248|p90.htm#i2671|Sir Roger Bigod|b. b 1140\nd. b 2 Aug 1221|p70.htm#i2075|Ida de Tony||p70.htm#i2076|Sir William Marshal|b. 1146\nd. 14 May 1219|p89.htm#i2644|Isabel de Clare|b. 1173\nd. 1220|p100.htm#i2977| | ||

| Marriage* | Groom=Gilbert de Lacy6,7,8 | |

| Birth* | circa 1210 | Norfolk, Norfolk, England7 |

| Marriage* | after 1230 | Groom=Sir John FitzGeoffrey9,7,10,11 |

| Marriage | before 12 April 1234 | Her maritagium included lands in Great Connell, co. Kildare, Groom=Sir John FitzGeoffrey12 |

| Burial* | Grey Friar's, Worcester, England7,13 | |

| Name Variation | Isabel le Bigod14 |

Family 1 | Gilbert de Lacy b. c 1200, d. b 25 Dec 1230 | |

| Children |

| |

Family 2 | Sir John FitzGeoffrey b. c 1205, d. 23 Nov 1258 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 8 Oct 2005 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 39.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 70-28.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 3-2.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 4-2.

- [S374] Douglas Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry, Bigod 2.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 70-29.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 13-3.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 73-29.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 4-3.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 16.

- [S374] Douglas Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry, Verdun 3.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 30.

- [S374] Douglas Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry, Verdun 4.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 120.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 12-4.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 73-30.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 24-6.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 1, p. 75.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 88.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 15-4.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 8-4.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 72-30.

Sir John FitzGeoffrey1

M, #2079, b. circa 1205, d. 23 November 1258

| Father* | Sir Geoffrey FitzPiers2,3,4 b. 1165, d. 14 Oct 1213 | |

| Mother* | Aveline de Clare2,3,4,5 b. c 1172, d. b 4 Jun 1225 | |

Sir John FitzGeoffrey|b. c 1205\nd. 23 Nov 1258|p70.htm#i2079|Sir Geoffrey FitzPiers|b. 1165\nd. 14 Oct 1213|p70.htm#i2093|Aveline de Clare|b. c 1172\nd. b 4 Jun 1225|p107.htm#i3192|Piers d. Lutegareshale|b. c 1134\nd. b 1198|p116.htm#i3463|Maud de Mandeville|b. c 1138|p116.htm#i3464|Roger de Clare|b. c 1116\nd. 1173|p86.htm#i2569|Maud de St. Hilary|b. c 1132|p86.htm#i2566| | ||

| Of | Shere & Shalford, Surrey; Fambridge Essex; Whaddon, Steeple Claydon, Quarrendon & Aylesbury, Buckingham; Cherhill & Winterslow, Wilts.; Pottersbury & Moulton, Northampton; Moreton Hampstead, Devonshire2,5 | |

| Birth* | circa 1205 | 5 |

| Marriage* | after 1230 | 2nd=Isabel Bigod6,2,4,7 |

| Marriage | before 12 April 1234 | Her maritagium included lands in Great Connell, co. Kildare, 2nd=Isabel Bigod5 |

| Death* | 23 November 1258 | 1,2,4,5 |

| DNB* | John fitz Geoffrey (c.1206-1258), justiciar of Ireland and baronial leader, was the son of Geoffrey fitz Peter, fourth earl of Essex, justiciar of England (d. 1213), and his second wife, Aveline, daughter of Roger de Clare, earl of Hertford, and widow of William de Munchensi. In 1227 John fitz Geoffrey gave the king 300 marks to have seisin of the lands that had descended to him by right of inheritance from his father. Geoffrey fitz Peter had intended these to be extensive, for King John had granted to him and his heirs from his marriage with Aveline the castle and honour of Berkhamsted. This grant, however, never came to fruition, and Berkhamsted, after Geoffrey's death, remained in the hands of the king. Thus, with the earldom of Essex passing to the descendants of Geoffrey's first marriage, John had to make do with such manors as Aylesbury and Steeple Claydon in Buckinghamshire, Exning in Suffolk, and Cherhill and Winterslow in Wiltshire, the last the only part of the honour of Berkhamsted that he obtained. John was a substantial magnate but, in terms of land held in hereditary right, not one of the first rank. Probably this situation, and the example of his father, who had risen in the king's service from humble origins to the earldom of Essex, was the spur to his long career in the royal administration. John began that career as sheriff of Yorkshire between 1234 and 1236. Then, in 1237, at the request of a parliament that conceded the king taxation, he was added to the king's council along with William (IV) de Warenne, earl of Surrey, and William de Ferrers, earl of Derby. If this elevation to the highest level reflected John's standing with his fellow magnates, in the ensuing years he gained and retained the confidence of the king. From 1237 until 1245 he seems to have acted as one of the stewards of the king's household, a post that he combined with the sheriffdom of Gloucestershire (1238–46) and more briefly with the office of chief justice of the southern forests (1241–2) and the seneschalship of Gascony (1243). He was thus well fitted for his long period in office as justiciar of Ireland (1245–56), where he had private interests through the dower of his wife, Isabel (daughter of Hugh Bigod, earl of Norfolk), who was the widow of Gilbert de Lacy of co. Meath. In 1254 Ireland was made part of the endowment of Edward, the king's son, and John fitz Geoffrey, between 1254 and 1258, became the prince's leading councillor. He also retained his place on the council of the king. His rewards from the latter, over his long career, had included the manors of Whaddon, Buckinghamshire, and Ringwood, Hampshire, the wardship of the land and heirs of Theobald Butler in Ireland (for which he paid 3000 marks), and ‘for his immense and laudable service’ the whole cantred of the Isles in Thomond. In the political crisis of 1258, however, John fitz Geoffrey was one of the king's chief opponents. Indeed, a later chronicle, the Westminster Flores historiarum, named him and Simon de Montfort as the ringleaders of the revolution. Certainly he was one of the seven magnates whose confederation in April 1258 began the process of reform. He was then one of the twelve chosen by the barons to reform the realm, and one of the council of fifteen imposed on the king by the provisions of Oxford. On 23 July 1258 he went with Roger (III) Bigod, earl of Norfolk, and Simon de Montfort to demand that the Londoners accept ‘whatever the barons should provide for the utility and foundation of the realm’ (Cronica maiorum et vicecomitum Londiniarum, 38–9). John's sudden death on 23 November 1258 thus deprived the new regime of one of its bastions. The Westminster Flores ascribed John's conduct to resentment at being removed from the justiciarship of Ireland. Like other leading magnates he was also provoked by the behaviour of the king's Poitevin half-brothers. His place in Edward's councils was threatened by their growing influence over the prince. In addition, he was engaged in a fierce dispute over the advowson of one of his manors—Shere in Surrey—with the youngest of the brothers, Aymer de Valence, earl of Pembroke and bishop-elect of Winchester. This reached a climax on 1 April 1258 when Valence's men attacked John's at Shere and killed one of them. When John demanded justice, the king refused to hear him. This episode helped spur the revolutionary action taken against the king at the Westminster parliament which opened a week later. Indignation at John's treatment spread the more easily because his brothers-in-law were Roger Bigod, earl of Norfolk, and Hugh Bigod, who was later appointed justiciar by the provisions of Oxford. Both were his colleagues among the seven original confederate magnates. John fitz Geoffrey was evidently a man of considerable parts, respected both by his fellow magnates and by the king. Indeed, despite his role in the revolution of 1258, when Henry III heard of John's death he ordered a solemn mass to be celebrated for his soul and donated a cloth of gold to cover his coffin. John was succeeded by his son, John fitz John, who became a leading supporter of Simon de Montfort. D. A. Carpenter, rev. Sources Calendar of the charter rolls, 6 vols., PRO (1903–27) · CPR · CClR · Calendar of the fine rolls, 22 vols., PRO (1911–62) · Calendar of the liberate rolls, 6 vols., PRO (1916–64) · PRO, Just 1/1187, m. 1 · Paris, Chron. · H. R. Luard, ed., Flores historiarum, 3 vols., Rolls Series, 95 (1890) · T. Stapleton, ed., De antiquis legibus liber: cronica majorum et vicecomitum Londoniarum, CS, 34 (1846) · R. F. Treharne and I. J. Sanders, eds., Documents of the baronial movement of reform and rebellion, 1258–1267 (1973) · H. W. Ridgeway, ‘Oxford (1258)’, Thirteenth century England, ed. P. R. Coss and S. D. Lloyd, 1 (1986) © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press D. A. Carpenter, ‘John fitz Geoffrey (c.1206-1258)’, rev., Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/38271, accessed 23 Sept 2005] John fitz Geoffrey (c.1206-1258): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/382718 | |

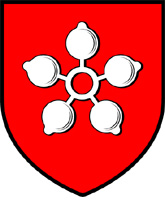

| Arms* | Esquartele d'or et de goules a la bordur de verree (Glover). Sealed, 13th cent.: Quarterly, a label of 5 points (Birch).9 | |

| Event-Misc | 1237 | He was sent to the Council of Lyons to protest against the papal tribute5 |

| Event-Misc | 1242 | He was granted the manor of Whaddon, Buckinghamshire5 |

| Occupation* | between 1245 and 1256 | Justiciar of Ireland1,3,4,9 |

| (Witness) Event-Misc | 21 January 1251 | His wardship and minority were granted for 3,000 marks to John Fitzgeoffrey, Principal=Theobald Butler10 |

| Feudal* | 3 May 1251 | Warham, Norf.9 |

| Event-Misc | 1253 | He was granted the cantred of the Isles of Thornon5 |

| Event-Misc* | 14 November 1258 | Trespasses were ordered by the Bp. Elect of Winchester, committed lately agst. Jn. Fitz Geoffry, by men of Farnham, and 300 m. recompense was made to him by guardians of the See, which 300 m. are now charged to the Bp.9 |

| Event-Misc | 22 July 1259 | John Fitz Geoffry, lately Custos of Bristol Castle, is dead, and is succeeded in said custody by his s. John Fitz John (P.R.)9 |

Family | Isabel Bigod b. c 1210 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 23 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 39.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 246C-28.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 4-3.

- [S374] Douglas Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry, Verdun 3.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 73-29.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 16.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 2, p. 36.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, II - 449.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 24-6.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 1, p. 75.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 88.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 72-30.

Theobald Butler1

M, #2080, b. 1242, d. 26 September 1285

|

| Father* | Theobald Butler2,3 b. c 1223, d. 1248 | |

| Mother* | Margery de Burgh2,3 d. a 1 Mar 1253 | |

Theobald Butler|b. 1242\nd. 26 Sep 1285|p70.htm#i2080|Theobald Butler|b. c 1223\nd. 1248|p92.htm#i2739|Margery de Burgh|d. a 1 Mar 1253|p92.htm#i2740|Theobald Butler|b. 1200\nd. 19 Jul 1230|p89.htm#i2665|Joan du Marais|d. b 4 Sep 1225|p284.htm#i8494|Richard de Burgh|b. c 1200\nd. c 17 Feb 1243|p92.htm#i2741|Hodierna de Gernon|d. 1219|p109.htm#i3246| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Of | Arklow, Wicklow, Ireland4 | |

| Birth* | 1242 | aged 6 in 1248 at his father's death1,3,4 |

| Marriage* | before 1268 | Principal=Joan FitzJohn1,2,5,3 |

| Death* | 26 September 1285 | Castle of Arklow, Arklow, Wicklow, Ireland1,3,6 |

| Burial* | Monastery of Arklow, Arklow, Wicklow, Ireland3 | |

| Probate | 5 January 1286 | 3 |

| Name Variation | Thebaud le Boteler4 | |

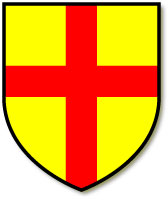

| Arms* | Or. A chief indented az. (St. George, Segar).7 | |

| Event-Misc | 21 January 1251 | His wardship and minority were granted for 3,000 marks to John Fitzgeoffrey, Witness=Sir John FitzGeoffrey3 |

| Event-Misc | 12 November 1279 | He owes £900, but for his services in Ireland, the King remits £100, and 400 m. for Kirkeham Church, Lancs., for whose advowson, the King gives him a sore-colored goshawk.6 |

| Feudal* | 20 April 1284 | 6 Kt. Fees in Tipperary6 |

| Event-Misc* | He took part with Edward I in the war with Scotland3 |

Family | Joan FitzJohn d. bt 25 Feb 1303 - 26 May 1303 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 9 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 39.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 73-30.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, II - 449.

- [S374] Douglas Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry, Butler 4.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 24-6.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 120.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 119.

Sir Edmund Butler Knt.1

M, #2081, b. circa 1282, d. 13 September 1321

| Father* | Theobald Butler1,2,3 b. 1242, d. 26 Sep 1285 | |

| Mother* | Joan FitzJohn1,2,3 d. bt 25 Feb 1303 - 26 May 1303 | |

Sir Edmund Butler Knt.|b. c 1282\nd. 13 Sep 1321|p70.htm#i2081|Theobald Butler|b. 1242\nd. 26 Sep 1285|p70.htm#i2080|Joan FitzJohn|d. bt 25 Feb 1303 - 26 May 1303|p70.htm#i2083|Theobald Butler|b. c 1223\nd. 1248|p92.htm#i2739|Margery de Burgh|d. a 1 Mar 1253|p92.htm#i2740|Sir John FitzGeoffrey|b. c 1205\nd. 23 Nov 1258|p70.htm#i2079|Isabel Bigod|b. c 1210|p70.htm#i2078| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Of | Knocktopher, co. Kilkenney, Rathkennan, co. Tipperary, Sopley, Hampshire, La Vacherie (in Cranley) and Shere, Surrey.4 | |

| Birth* | circa 1282 | was of age 13 Jan 13043 |

| Marriage* | 1302 | Principal=Joan FitzJohn1,5,6,7,8 |

| Death* | 13 September 1321 | London, Middlesex, England, after returning from a pilgrimage to St. James Compostella, Spain.1,5,2,8,9 |

| Burial* | 9 November 1321 | Gowran, Kilkenny, Ireland8 |

| DNB* | Butler, Edmund, earl of Carrick (d. 1321), justiciar of Ireland, was a younger son of Theobald Butler (d. 1285), butler of Ireland, and Joan, daughter of John Fitzgeoffrey. He may have visited England as early as 1289, and was certainly of age at the death of his childless elder brother, Theobald (V), in 1299. The death of his mother in 1303 brought him a share of the Fitzjohn lands in England and Ireland, and he also acquired some of the English and Irish estates of the Pippards. In 1302 he married Joan, a daughter of John fitz Thomas Fitzgerald (d. 1316), later first earl of Kildare. In 1303 Butler was ready to join an Irish expeditionary force to Scotland, but was asked to remain in Ireland for its security. He acted as deputy justiciar from November 1304 to May 1305, when John Wogan was out of the country. During a visit to England in 1309–10 he was knighted by Edward II. He was deputy again from August 1312 to June 1314. In the winter of 1312–13 he organized a major campaign in Leinster which brought the Uí Bhroin of Wicklow to the peace. At a Michaelmas feast in Dublin in 1313 he is said to have dubbed thirty knights. He served once more as justiciar from February 1315 to April 1318, for the last year under Roger Mortimer, who had been appointed king's lieutenant. His period of office coincided both with the invasion of Ireland by the Scots under Edward Bruce and with the great famine of 1316–17. He brought the magnates of Ireland to Dundalk to confront Bruce in July 1315. When the Scots retreated north, he did not follow, assuming (reasonably but wrongly) that the earl of Ulster was capable of defeating them. When Bruce came south early in 1316, he was present at an inconclusive battle at Skerries in Kildare, after which he and other magnates gave hostages and assurances of loyalty to John Hotham, the king's emissary. A year later, when Robert Bruce had joined his brother in Ireland, Butler left Dublin to its own devices and concentrated upon mustering Munster against the Scots. The army he raised confronted them near Limerick in April 1317, leaving King Robert's forces no choice but to retreat, starving. Shortly before Butler died, Edward II issued a declaration ‘to clear the fair fame of Edmund le Botiller who has been accused of having assisted the Scots in Ireland, that he has borne himself well and faithfully towards the king’ (CPR, 1317–21, 535). Any suspicions seem groundless. It fell to Butler to organize a highly regionalized country in the most difficult circumstances; if his performance was not glorious, it compared favourably with that of Edward II himself and of those who defended the north of England at the same period. On 1 September 1315 Edward II had granted Butler the manors of Carrick-on-Suir and Roscrea in Tipperary, with the title of earl of Carrick. He was also given return of writs in three Tipperary cantreds, a grant that foreshadowed the later liberty of Tipperary. He was occasionally referred to as earl by the king (and in April 1317 by Pope John XXII); but, perhaps because of its limited endowment, his comital status failed to gain acceptance, and he did not normally use the title. In 1320 the pope released him from a vow to undertake a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela because of the state of Ireland. He spent his last months in England, in March 1321 arranging a marriage (which was outrun by events) between his daughter, Joan, and Roger, the second son of Roger Mortimer, involving the settlement of the Mortimer lands in Ireland on the couple. He died in London on or shortly before 13 September 1321, and was buried the following November at Gowran (Kilkenny), where the bishop of Ossory and the prior of the hospitallers had earlier agreed to supply four priests to pray for his soul and those of members of his family. He was succeeded by his son, James Butler, who in 1328 became first earl of Ormond. Robin Frame Sources Chancery records · E. Curtis, ed., Calendar of Ormond deeds, IMC, 1: 1172–1350 (1932) · J. T. Gilbert, ed., Chartularies of St Mary's Abbey, Dublin: with the register of its house at Dunbrody and annals of Ireland, 2, Rolls Series, 80 (1884) · A. J. Otway-Ruthven, A history of medieval Ireland (1968) · R. Frame, ‘The Bruces in Ireland, 1315–18’, Irish Historical Studies, 19 (1974–5), 3–37 · R. Frame, ‘The campaign against the Scots in Munster, 1317’, Irish Historical Studies, 24 (1984–5), 361–72 · R. Frame, English lordship in Ireland, 1318–1361 (1982) · J. R. S. Phillips, ‘The mission of John de Hotham to Ireland, 1315–1316’, England and Ireland in the later middle ages, ed. J. Lydon (1981), 62–85 · The annals of Ireland by Friar John Clyn and Thady Dowling: together with the annals of Ross, ed. R. Butler, Irish Archaeological Society (1849) · CEPR letters, 2.196, 415, 439 · PRO · GEC, Peerage Archives NL Ire., deeds © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Robin Frame, ‘Butler, Edmund, earl of Carrick (d. 1321)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/50020, accessed 23 Sept 2005] Edmund Butler (d. 1321): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5002010 | |

| Name Variation | le Boteler | |

| Event-Misc | 1299 | He was heir to his brother Theobald4 |

| Event-Misc* | 30 August 1300 | He did homage for his brother's lands9 |

| Event-Misc | 13 January 1304 | He had livery of his mother's lands in England9 |

| Event-Misc | 16 October 1306 | He was lately vice-Justiciary of Ireland9 |

| Feudal* | Easter 1307 | a barony at Tullath Offelmyth, Carlow, as 4 Kt. Fees9 |

| Knighted* | 1309 | London, by Edward II3,4 |

| Occupation* | between 1312 and 1317 | Justiciar and Chief Governor of Ireland1,3 |

| Event-Misc | 20 September 1313 | Dublin, Ireland, He created 30 knights at a feast11 |

| Event-Misc | 1316 | He commanded the English forces in Ireland against the invasion of Edward Bruce4 |

Family | Joan FitzJohn | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 23 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 39.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 24-6.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, II - 449.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Butler 5.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 73-31.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Butler 10.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Butler 9.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, II - 450.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 116.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 48.

Sir John FitzThomas FitzGerald Knt.1

M, #2082, b. between 1260 and 1270, d. 12 September 1316

| Father* | Thomas FitzMaurice FitzGerald2,3 d. 1271 | |

| Mother* | Rohesia de St. Michael3 | |

Sir John FitzThomas FitzGerald Knt.|b. bt 1260 - 1270\nd. 12 Sep 1316|p70.htm#i2082|Thomas FitzMaurice FitzGerald|d. 1271|p365.htm#i10930|Rohesia de St. Michael||p493.htm#i14774|Sir Maurice FitzGerald "the Friar"|b. 1190\nd. 20 May 1257|p365.htm#i10931|Juliana de Cogan||p365.htm#i10932||||||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | Principal=Blanche Roche4,5,3 | |

| Birth* | between 1260 and 1270 | 6 |

| Death* | 12 September 1316 | Laraghbryan, Maynooth, Kildare, Ireland7,3 |

| Burial* | Church of the Friars Minor, Kildare, Ireland7 | |

| Note | He received the hereditary claims of Juliana de Cogan and Amabil, daughter of Maurice FitzMaurice and Matilda de Prendergast8 | |

| Note* | A legend states that when he was a baby in the Castle of Woodstock near Athy in Kildare, a fire broke out, and he was rescued by a monkey who held him in his arms while he climbed a tower.3 | |