Sir William de Warenne1

M, #3001, b. circa 1166, d. 27 May 1240

|

| Father* | Sir Hamelin Plantagenet2,3,1,4 b. c 1130, d. 7 May 1202 | |

| Mother* | Isabel de Warene2,3,1,4 b. c 1137, d. 12 Jul 1203 | |

Sir William de Warenne|b. c 1166\nd. 27 May 1240|p101.htm#i3001|Sir Hamelin Plantagenet|b. c 1130\nd. 7 May 1202|p70.htm#i2077|Isabel de Warene|b. c 1137\nd. 12 Jul 1203|p101.htm#i3002|Geoffrey V. "the Fair" Plantagenet|b. 24 Nov 1113\nd. 7 Sep 1151|p55.htm#i1624|Anonyma (?)||p457.htm#i13698|Sir William de Warenne|b. 1118\nd. 31 Mar 1148|p101.htm#i3004|Ela Talvas|b. c 1120\nd. 4 Oct 1174|p101.htm#i3005| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1166 | Surrey, England3 |

| Marriage* | before 1207 | Bride=Maud d' Aubeney5 |

| Marriage* | before 13 October 1225 | 2nd=Maud Marshal6,3,1,5 |

| Death* | 27 May 1240 | London, England6,3,1,5 |

| Burial* | Before the High Altar, Lewes Priory, Sussex, England3,7 | |

| Name Variation | Sir William de Warene6,4 | |

| Name Variation | William Plantagenet de Warren3 | |

| Event-Misc | 1197 | Rouen, Normandy, France, He witnessed a charter for King Richard I5 |

| Event-Misc | 12 May 1202 | He had seisin of his father's lands5,8 |

| Event-Misc | 19 April 1205 | King John granted him Grantham and Stamford, Lincolnshire to compensate him for the loss of his lands in Normandy5,8 |

| Event-Misc | 30 November 1206 | He was instructed to escort the King of the Scots to York5,8 |

| Event-Misc | 20 August 1212 | He was one of three given custody of the castles of Bambrough and Newcastle-on-Tyne8 |

| Event-Misc | May 1213 | Dover, He was a party to John's submission to the Pope8 |

| Event-Misc | January 1214/15 | He came to London with the Archbishop to discuss grievances8 |

| Event-Misc | 10 May 1215 | He was surety for the King's promises to make concession to the barons8 |

| Event-Misc | 24 May 1215 | We was with the barons in their seizure of London8 |

| (King) Magna Carta | 12 June 1215 | Runningmede, Surrey, England, King=John Lackland9,5,10,11,12,13 |

| Event-Misc | 16 May 1216 | He was Warden of the Cinque Ports8 |

| Event-Misc | 1217 | He was sheriff of Surrey8 |

| Event-Misc | 24 August 1217 | He took part in the naval battle in which Eustace the Monk was defeated and slain5,8 |

| Event-Misc* | 1220 | Berwick, He was appointed to meet the King of Scotland5 |

| Event-Misc | February 1222/23 | He went on pilgrimage to St. James (Spain)8 |

| Event-Misc | 1227 | He joined the Earl of Cornwall at Stamford in his revolt against the King, but by Christmas was with the King again.5,8 |

| Event-Misc | 1230 | He was appointed Justiciar of England8 |

| Event-Misc | July 1230 | He was warden of the ports and seacoast of Suffolk, Essex, and Norfolk8 |

| Event-Misc | June 1234 | He with another were granted the castles of Bramber and Knapp8 |

| Event-Misc | 20 January 1235/36 | Westminster, He acted as Butler at the Coronation of Queen Eleanor of Provence, in place of his son-in-law, the Earl of Arundel5,8 |

| Event-Misc | 1237 | He joined the King's Council8 |

| Event-Misc | 1238 | He dealt with a quarrel at Oxford between the scholars and the Romans who had accompanied the Papal Legate8 |

| Title* | 6th Earl of Surrey, Baron of Lewes, Warden of the Cinque Ports, Sheriff of Surrey, Justiciar of England, Custodian of bramber and Knapp Castles, King's Counsellor5 | |

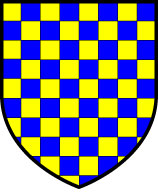

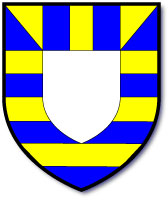

| Arms* | checky or and azure14,5 |

Family | Maud Marshal b. c 1192, d. 27 Mar 1248 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 5 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 151-1.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 83-26.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Warenne 2.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Warenne 3.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 83-27.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 266.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 260.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Longespée 3.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 56-27.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 60-28.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 8.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 34.

- [S318] Charles Evans, "Arms of Coys and Warren", p. 161.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 151-2.

Isabel de Warene1

F, #3002, b. circa 1137, d. 12 July 1203

| Father* | Sir William de Warenne2,3 b. 1118, d. 31 Mar 1148 | |

| Mother* | Ela Talvas2,4,3 b. c 1120, d. 4 Oct 1174 | |

Isabel de Warene|b. c 1137\nd. 12 Jul 1203|p101.htm#i3002|Sir William de Warenne|b. 1118\nd. 31 Mar 1148|p101.htm#i3004|Ela Talvas|b. c 1120\nd. 4 Oct 1174|p101.htm#i3005|Sir William de Warenne|b. 1071\nd. 11 May 1138|p101.htm#i3006|Isabel de Vermandois|b. 1081\nd. 13 Feb 1131|p64.htm#i1915|William I. Talvas|b. c 1090\nd. 30 Jun 1171|p122.htm#i3657|Hélie of Burgundy|b. Nov 1080\nd. 28 Feb 1141/42|p122.htm#i3658| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1137 | Surrey, England4 |

| Marriage* | before 6 November 1153 | Groom=Sir William of Blois1,4 |

| Marriage* | April 1164 | Groom=Sir Hamelin Plantagenet1,4,3 |

| Death* | 12 July 1203 | Lewes, Sussex, England4,3,5 |

| Burial* | Chapter House, Lewes, Sussex, England3 | |

| DNB* | Warenne, Isabel de, suo jure countess of Surrey (d. 1203), magnate, was the daughter and only surviving heir of William (III) de Warenne, earl of Surrey (c.1119-1148), and Ela (d. 1174), daughter of Guillaume Talvas, count of Ponthieu. This position ensured her matches of considerable importance. In 1148, the year of her father's death, and at a critical moment in the civil war, she married William of Blois (d. 1159), the younger son of King Stephen, as part of the king's attempt to ensure control of the Warenne estates. About 1162–3, in what may have been a love match, William FitzEmpress, the brother of Henry II, sought her hand in marriage. However, Thomas Becket, archbishop of Canterbury, objected on grounds of consanguinity, earning the lasting enmity of the allegedly heart-broken William. Isabel's reaction is, unfortunately, not recorded. In April 1164, with a valuable trousseau worth £41. 10s. 8d., she married Hamelin of Anjou (d. 1202), the half-brother of Henry II, who by this marriage came to be known as Hamelin de Warenne. Isabel had one son, William (IV) de Warenne, who succeeded to the earldom and married Matilda, daughter of William Marshal (d. 1219) and widow of Hugh Bigod (d. 1225). Her three daughters with Hamelin all married twice: Ela married Robert of Naburn and William fitz William (d. 1219); Isabel married Robert de Lacy and Gilbert de l'Aigle, lord of Pevensey; Matilda married Henry, count of Eu (d. 1190/91) and Henry de Stuteville: by the former marriage Isabel became grandmother of the powerful Alice, countess of Eu (d. 1246). As a countess and great heiress Isabel was involved in the secular and religious patronage of the Warenne estates. Of particular interest is her patronage during both marriages, and as a widow, of the chief English Cluniac house, Lewes Priory, Sussex, founded by her grandparents. She was present at Lambeth when a long-standing dispute between the great abbey of Cluny and her husband was resolved on 10 June 1201. She and Earl Hamelin also patronized St Mary's Abbey and West Dereham Abbey, Norfolk; St Katherine's Priory, Lincoln (c.1198–1202); and the chapel of St Philip and St James in their castle at Conisbrough (1180–89). In 1202–3, as a widow, she confirmed various grants to these houses, and was involved in pleas in her Yorkshire estates. Isabel died on 12 July 1203 and was buried alongside Earl Hamelin in the chapter house at Lewes, the traditional Warenne resting place. She was commemorated by the monks of Beauchief Abbey on 12 July. Susan M. Johns Sources W. Farrer and others, eds., Early Yorkshire charters, 12 vols. (1914–65) · R. Howlett, ed., Chronicles of the reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I, 4, Rolls Series, 82 (1889) · Stephen of Rouen, ‘Draco Normannicus’, ed. R. Howlett, Chronicles of the reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I, 2, 589–781, Rolls Series, 82 (1885) · Pipe rolls, 10 Henry II · GEC, Peerage, new edn · Curia regis rolls preserved in the Public Record Office (1922–) © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Susan M. Johns, ‘Warenne, Isabel de, suo jure countess of Surrey (d. 1203)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/28733, accessed 24 Sept 2005] Isabel de Warenne (d. 1203): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/287336 | |

| Title* | De jure Countess of Surrey3 |

Family | Sir Hamelin Plantagenet b. c 1130, d. 7 May 1202 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 83-26.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 83-25.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Warenne 2.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 260.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 123-27.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 151-1.

Sir William of Blois1

M, #3003, b. circa 1137, d. 11 October 1159

| Father* | Stephen of Blois2 b. bt 1095 - 1096, d. 25 Oct 1154 | |

| Mother* | Maud of Boulogne2 b. c 1105, d. 3 May 1152 | |

Sir William of Blois|b. c 1137\nd. 11 Oct 1159|p101.htm#i3003|Stephen of Blois|b. bt 1095 - 1096\nd. 25 Oct 1154|p123.htm#i3669|Maud of Boulogne|b. c 1105\nd. 3 May 1152|p123.htm#i3670|Count Stephen I. of Blois|b. 1045\nd. 13 Jul 1102|p123.htm#i3673|Adela of Normandy|b. 1062\nd. 8 Mar 1108|p123.htm#i3674|Count Eustace I. of Boulogne|b. c 1058\nd. a 1125|p127.htm#i3806|Mary of Scotland|d. 31 May 1116|p127.htm#i3807| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1137 | 2 |

| Marriage* | before 6 November 1153 | 1st=Isabel de Warene1,2 |

| Death* | 11 October 1159 | Toulouse, France2 |

| Burial* | Montmorillion, Poitou, France3 | |

| Name Variation | William II (?)2 | |

| Name Variation | William FitzRoy3 | |

| Title* | Count of Boulogne and Mortain, 4th Earl of Surrey3 |

| Last Edited | 28 Jul 2004 |

Sir William de Warenne1

Sir William de Warenne1

M, #3004, b. 1118, d. 31 March 1148

| Father* | Sir William de Warenne2 b. 1071, d. 11 May 1138 | |

| Mother* | Isabel de Vermandois1 b. 1081, d. 13 Feb 1131 | |

Sir William de Warenne|b. 1118\nd. 31 Mar 1148|p101.htm#i3004|Sir William de Warenne|b. 1071\nd. 11 May 1138|p101.htm#i3006|Isabel de Vermandois|b. 1081\nd. 13 Feb 1131|p64.htm#i1915|William de Warenne|d. 24 Jun 1088|p101.htm#i3007|Gundred (?)|b. c 1051\nd. 27 May 1085|p101.htm#i3008|Hugh Magnus of France|b. 1057\nd. 18 Oct 1101|p64.htm#i1916|Adelaide de Vermandois|b. c 1062\nd. 28 Sep 1124|p64.htm#i1917| | ||

| Birth* | 1118 | 1,3 |

| Birth | circa 1119 | 4 |

| Marriage* | 1st=Ela Talvas1,3,5 | |

| Death* | 31 March 1148 | Leodicia, Anatolia, |in the rear guard of the King of France which was cut apart1,3,6 |

| DNB* | Warenne, William (III) de, third earl of Surrey [Earl Warenne] (c.1119-1148), magnate and crusader, was the eldest of the five children of William (II) de Warenne (d. 1138) and Isabel de Vermandois (d. 1147). His younger siblings included Ada, later countess of Huntingdon and Northumberland, and Reginald de Warenne. It was through his mother that he made the two most important family connections in his life: his eldest half-brother, Waleran, count of Meulan, the elder of the well-known Beaumont twins, and his distant cousin, Louis VII of France. Warenne married Ela, the daughter of Guillaume Talvas, count of Ponthieu, and Ela, daughter of Odo Borel, duke of Burgundy. She died on 4 October 1174. Their only child and Warenne's heir was a daughter, Isabel de Warenne (d. 1203), who married William, son of King Stephen, and after his death, Hamelin, half-brother of King Henry II. Between 1130 and 1138 Warenne appeared with his brother Ralph as co-grantor or witness in several of their father's charters, but his first known independent action was one which presaged a life of military misfortune. He was among those ‘hot-headed youths’ (as Orderic Vitalis called them) who deserted King Stephen during his unsuccessful attempt to take Normandy in 1137. Probably in 1138 Warenne's father died, and he succeeded as earl of Surrey, though he consistently styled himself as Earl Warenne. In the summer of 1138 he or his father witnessed and possibly acted as guarantor for Roger, earl of Warwick, in an important charter in which Roger, husband of William (III)'s sister Gundreda, settled marriage arrangements between Roger's daughter and the chamberlain Geoffrey of Clinton. By the end of the year he had joined Waleran in Normandy and acted along with him as a witness to an agreement made in Rouen on 18 December. The brothers proceeded to their kinsman King Louis's court on an embassy from Stephen. By no later than 1139 Warenne had returned to England, probably with Waleran, most likely to attend his sister Ada's marriage to Henry, son of King David of Scotland. At that time he began his attendance at Stephen's court, where he became a regular witness to royal charters (at least a dozen between then and 1147) and began a career of unbroken, if not always distinguished, service to that troubled monarch. The low point in Warenne's service to Stephen was at the battle of Lincoln on 2 February 1141, at which he and Waleran were among those who panicked and ran when they faced the first charge of Earl Robert of Gloucester's army, leaving the king to be captured. That it was panic rather than treachery that caused the flight could be seen by their support of Queen Matilda during Stephen's captivity and Warenne's appearance at the king's court after his release. Warenne redeemed himself on 14 September of that year and achieved the brightest moment of his military career when he led the Flemish mercenaries (usually under the command of William of Ypres) in taking Robert of Gloucester prisoner at Stockbridge. His activities in the following years included an appearance at Stephen's Christmas court, held at Canterbury, and an expedition against the town of St Albans, which he and three of the king's other captains were kept from burning by the payment of a rich bribe by Abbot Geoffrey of St Albans. The next word of Warenne's military activity came in January 1144, during the king's last effort to win Normandy from Geoffrey of Anjou. When the city of Rouen surrendered to Geoffrey's forces, Stephen's men refused to give up the royal castle, and, led by Warenne's mercenaries, they held out for another three months before surrendering the castle of Neufchâtel-en-Bray. A double irony of this event is that Earl William was not identified specifically as having been present at this exercise in gallant futility, and that one of the leaders to whom his men surrendered was Count Waleran, that half-brother who had most guided his early career and who had been forced by then to take the Angevin side to defend his Norman holdings. If Warenne was indeed in Normandy at some time during the year, he left for England, where he was present on two occasions at the royal court during 1144 and 1145. On 24 March, Palm Sunday of 1146, motivated perhaps by the example of his royal cousin and of Count Waleran, or by the rhetoric of an emotionally moving occasion, or by the desire to leave behind bad memories of the Anglo-Norman war, Warenne took the cross near Vézelay. After making some confirmatory grants to Lewes Priory and making his brother Reginald administrator of the honour of Warenne in his absence, he departed in June 1147, and met up with the French king, Louis, at Worms on the Rhine. He served in the king's personal guard, in which capacity he suffered loss of men and materials in an early encounter with the enemy. On 19 January 1148 he was among those in Louis's rearguard who were butchered in the defiles of Laodicea, and neither the wishful thinking of his brother Reginald nor the rumours of his survival that reached the northern chronicler John of Hexham would bring Warenne home again. Although his short life meant that Warenne could not compete with his comital contemporaries in the field of religious benefactions, he did fulfil his obligations with donations to the family foundations of Lewes Priory and, to a lesser extent, Castle Acre Priory. He also made grants to the abbey of St Mary, York, and the templars at Saddlescombe, and he founded the priory of the Holy Sepulchre, Thetford, and possibly Thetford Hospital as well. He issued confirmations to Battle Abbey and Coxford and Nostell priories. Victoria Chandler Sources W. Farrer and others, eds., Early Yorkshire charters, 12 vols. (1914–65), vol. 8 · GEC, Peerage · Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist. · Henry, archdeacon of Huntingdon, Historia Anglorum, ed. D. E. Greenway, OMT (1996) · Reg. RAN, vol. 3 · D. Crouch, The Beaumont twins: the roots and branches of power in the twelfth century, Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought, 4th ser., 1 (1986) · Chronique de Robert de Torigni, ed. L. Delisle, 2 vols. (Rouen, 1872–3) · Odo of Deuil, De profectione Ludovici VII in orientem, ed. and trans. V. G. Berry (1948) · G. W. Watson, ‘William de Warenne, earl of Surrey’, The Genealogist, new ser., 11 (1894–5), 132 · John of Hexham, ‘Historia regum continuata’, Symeon of Durham, Opera, vol. 2 · D. Crouch, ‘Geoffrey de Clinton and Roger, earl of Warwick: new men and magnates in the reign of Henry I’, BIHR, 55 (1982), 113–24 Wealth at death significant landholder in several counties © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Victoria Chandler, ‘Warenne, William (III) de, third earl of Surrey (c.1119-1148)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/28738, accessed 24 Sept 2005] William (III) de Warenne (c.1119-1148): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/287387 | |

| Name Variation | William de Warren3 | |

| Event-Misc* | June 1137 | "He was among those who deserted King Stephen's army in Normandy, where it was said Stephen held William and other youths and did his best to pacify them, but did not dare make them fight."8 |

| Event-Misc* | 18 December 1138 | Rouen, William de Warenne was with his half-brother, Waleran de Beaumont, Principal=Waleran de Beaumont8 |

| (Stephen) Battle-Lincoln | 2 February 1140/41 | Principal=Stephen of Blois, Principal=Ranulph de Gernon9 |

| Event-Misc | 24 March 1145/46 | He took the cross8 |

| Event-Misc | June 1147 | He set forth on Crusade8 |

Family | Ela Talvas b. c 1120, d. 4 Oct 1174 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 83-25.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 83-24.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 259.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Warenne 2.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 266.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 260.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 28.

Ela Talvas1

F, #3005, b. circa 1120, d. 4 October 1174

| Father* | William III Talvas2,3,4 b. c 1090, d. 30 Jun 1171 | |

| Mother* | Hélie of Burgundy2,5 b. Nov 1080, d. 28 Feb 1141/42 | |

Ela Talvas|b. c 1120\nd. 4 Oct 1174|p101.htm#i3005|William III Talvas|b. c 1090\nd. 30 Jun 1171|p122.htm#i3657|Hélie of Burgundy|b. Nov 1080\nd. 28 Feb 1141/42|p122.htm#i3658|Robert I. de Bellême|b. c 1054\nd. 08 May, after 1131|p122.htm#i3659|Agnes of Pontieu|d. b 1103|p122.htm#i3660|Eudes I. Borel|b. c 1058\nd. 23 Mar 1102/3|p123.htm#i3661|Maud d. B. (?)|b. c 1062\nd. a 1103|p123.htm#i3662| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1120 | 2 |

| Marriage* | Groom=Sir William de Warenne1,2,3 | |

| Marriage* | 1149 | 2nd=Patrick d' Evereux2,6 |

| Death* | 4 October 1174 | Salisbury, Wiltshire, England2,6 |

| Death | 10 October 1174 | 7,8 |

| Name Variation | Ela d' Alencon2 |

Family 1 | Sir William de Warenne b. 1118, d. 31 Mar 1148 | |

| Children |

| |

Family 2 | Patrick d' Evereux b. b 1120, d. 27 Mar 1168 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 27 May 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 83-25.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Warenne 2.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 108-25.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 108-25.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 108-26.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 108-26.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 79.

Sir William de Warenne1

M, #3006, b. 1071, d. 11 May 1138

| Father* | William de Warenne1,2 d. 24 Jun 1088 | |

| Mother* | Gundred (?)1,3 b. c 1051, d. 27 May 1085 | |

Sir William de Warenne|b. 1071\nd. 11 May 1138|p101.htm#i3006|William de Warenne|d. 24 Jun 1088|p101.htm#i3007|Gundred (?)|b. c 1051\nd. 27 May 1085|p101.htm#i3008|Rodulf de Warenne|b. c 998|p140.htm#i4181|Beatrix d. Crepon||p319.htm#i9568|Gerbod o. St. Omer||p150.htm#i4475|Maud of Flanders|b. 1032\nd. 3 Nov 1083|p59.htm#i1769| | ||

| Birth* | 1071 | Sussex, England3 |

| Marriage* | 1118 | 2nd=Isabel de Vermandois1,3,4 |

| Marriage* | 2nd=Isabel de Beaumont5 | |

| Burial* | Chapter House, Lewes, at his father's feet3,6 | |

| Death* | 11 May 1138 | 1,2 |

| DNB* | Warenne, William (II) de, second earl of Surrey [Earl Warenne] (d. 1138), magnate, the eldest son of William (I) de Warenne (d. 1088) and Gundrada de Warenne (d. 1085), sister of Gerbod the Fleming, earl of Chester, succeeded to the newly created earldom of Surrey on his father's death on 24 June 1088. He usually styled himself ‘Willelmus comes de Warenna’ and less often ‘Willelmus de Warenna comes Sudreie’ (or ‘Surregie’, ‘Suthreie’, or ‘Sudreie’). He was a great-great-nephew of the Duchess Gunnor and thus a kinsman of the Norman kings. From his father he inherited one of the largest of all Domesday estates, with lands worth about £1165 a year spread across thirteen counties, concentrated in Sussex (the rape of Lewes), Norfolk (including Castle Acre), and Yorkshire (Conisbrough). He was a benefactor of the great Cluniac priory of St Pancras, Lewes, which his parents had founded about 1077, and also patronized the abbeys of St Evroult and St Amand and the priories of Castle Acre, Longueville, Wymondham, Pontefract, and Bellencombre. The Hyde chronicler reports that whereas William (II) de Warenne received his father's lands in England, his younger brother, Reginald, received the maternal lands in Flanders. The chronicler says nothing of the paternal lands in Upper Normandy, centring on the castles of Mortemer-sur-Eaulne and Bellencombre in the Pays de Caux, but they probably went to Reginald as well, and when Reginald died after 1106 passed to Earl William. In 1118 or 1119 Earl William, probably in his later forties, married Isabel de Vermandois (d. 1147), granddaughter of Henri I of France and widow of the Beaumont magnate Robert, count of Meulan (d. 1118); the offspring of that marriage were the twins Waleran, count of Meulan, and Robert, earl of Leicester, and five or six other children. She and Earl William had five children, including William (III) de Warenne, earl of Surrey (c.1119-1148), and Reginald de Warenne (1121x6-1178/9). Through their daughter Ada, countess of Northumberland (c.1123-1178), Isabel and Earl William were the grandparents of Malcolm IV and William the Lion, kings of Scotland. Henry of Huntingdon reports that Isabel's first husband, Robert, count of Meulan, had suffered the humiliation of having his wife carried off by ‘a certain earl’. The circumstances and details of this scandalous event cannot be discerned, but it was not long after Count Robert's death in June 1118 that Isabel married Earl William. Unlike his father William (I) de Warenne, a veteran of Hastings and a staunch royalist, Earl William was seldom at the court of William Rufus (he attested only one or possibly two of the king's surviving charters) and showed little respect for Henry I during his initial years. The trouble may have begun when, some time in the 1090s, Earl William tried unsuccessfully to win the hand of Matilda, the eldest daughter of King Malcolm and Queen Margaret of Scotland, who was later to marry Henry I. According to the late testimony of Master Wace, Earl William ridiculed the young Henry for his pedantic approach to the joyous aristocratic pastime of hunting, mocking him with the nickname ‘Stagfoot’ for having examined the sport so studiously that he could tell the number of tines in a stag's antlers simply by examining his footprint. At some point after his accession in 1100 Henry tried to win Earl William's support by offering him one of his bastard daughters in marriage, but Archbishop Anselm blocked the project on grounds of consanguinity. When Robert Curthose, duke of Normandy, invaded England on 20 July 1101, Earl William and many other barons joined the ducal side, but Henry bought off Duke Robert with an annuity of 3000 marks, and Earl William was left stranded. For the violation of his homage to the king, and perhaps as a punishment for acts of violence by his men in Norfolk, he was disseised of his English estates and forced into exile. Earl William complained to Robert Curthose in Normandy of being deprived of his vast English estates, and recovered them when the duke crossed impulsively to England in 1103, interceded with Henry on the earl's behalf, and agreed to relinquish the annuity. Thenceforth Earl William gradually regained the king's confidence and became a trusted member of his familia. At the climactic battle of Tinchebrai in September 1106 he commanded a division of the victorious royal army, and from then until Henry's death in 1135 he is known to have been in the king's company on each of the royal sojourns in Normandy and England. He attended the royal council at Nottingham on 17 October 1109 and was a surety for the king in his treaty of Dover with Robert, count of Flanders, on 17 May 1110. In 1111 he served as a judge in the Norman ducal court. In 1119, on the eve of Henry's crucial battle against Louis VI at Brémule, with many Norman lords in rebellion, Earl William is said to have told the king, ‘There is nobody who can persuade me to treason … I and my kinsmen here and now place ourselves in mortal opposition to the king of France and are totally faithful to you.’ (Liber monasterii de Hyda, 316–7). With Earl William's force in the vanguard, Henry's army won a decisive victory. Henry had taken steps to cement (or reward) Earl William's loyalty by adding to his holdings in England and Normandy. William received (c.1106–21) the great royal manor of Wakefield in Yorkshire, possibly relinquishing lands in Huntingdonshire, Bedfordshire, and Cambridgeshire in partial exchange for it. Henry also ceded to Earl William the castlery of St Saëns shortly after its lord, Elias de St Saëns, fled Normandy, c.1110, with Henry's nephew and adversary, William Clito. St Saëns, three miles up the River Varenne from Bellencombre, constituted a valuable addition to Earl William's estates in Upper Normandy and bound him even more closely to the royal cause. Should Clito ever regain Normandy from Henry I, Clito's friend and guardian Elias would surely recover St Saëns. (His family had recovered the castlery by 1150.) Thus, after his initial false step, William de Warenne became the most ardent of royalists. He attested no fewer than sixty-nine of Henry's charters, and in the reign's one surviving pipe roll (1130) he is recorded as receiving the third highest geld exemption of any English magnate (£104 8s. 11d.)—reflecting both the extent of his landed wealth and the warmth of the king's favour. He was at Henry's deathbed at Lyons-la-Forêt in 1135 and was one of five comites who escorted his corpse to Rouen for embalming. Afterwards the Norman magnates appointed Earl William governor of Rouen and the Pays de Caux. He was back in England in the spring of 1136 at Stephen's Easter court at Westminster (22 March) and at Oxford shortly afterwards, where he attested Stephen's charter of liberties for the church. His last attestations of royal charters occurred on Stephen's expedition against Exeter in mid-1136, but there is good reason to believe that he was alive in 1137. He probably died on 11 May 1138, and was buried with his parents in Lewes Priory. C. Warren Hollister Sources W. Farrer and others, eds., Early Yorkshire charters, 12 vols. (1914–65), vol. 8 · GEC, Peerage, new edn, vol. 12/1 · W. Farrer, Honors and knights' fees … from the eleventh to the fourteenth century, 3 (1925) · L. C. Loyd, ‘The origin of the family of Warenne’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 31 (1932–4), 97–113 · C. W. Hollister, Monarchy, magnates, and institutions in the Anglo-Norman world (1986) · J. O. Prestwich, ‘The military household of the Norman kings’, EngHR, 96 (1981), 1–35, esp. 14–15 · I. J. Sanders, English baronies: a study of their origin and descent, 1086–1327 (1960), 128–9 · William of Jumièges, Gesta Normannorum ducum, ed. J. Marx (Rouen and Paris, 1914) · S. Anselmi Cantuariensis archiepiscopi opera omnia, ed. F. S. Schmitt, 6 vols. (1938–61) · E. Edwards, ed., Liber monasterii de Hyda, Rolls Series, 45 (1866) · Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist., 4.180–82, 222, 272 · J. le Patousel, The Norman empire (1976) · Reg. RAN, vols. 2–3 · Lewes cartulary, BL, Cotton MS, Vespasian F15 [reproduced in Sussex Record Society, ed. L. F. Salzman, 2.15], fol.105v © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press C. Warren Hollister, ‘Warenne, William (II) de, second earl of Surrey (d. 1138)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/28737, accessed 23 Sept 2005] William (II) de Warenne (d. 1138): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/287377 | |

| Title | 2nd Earl of Surrey6 | |

| Name Variation | William de Warrenne3 | |

| Event-Misc* | 1090 | William de Warenne fought in Normandy against Robert de Belleme, a supporter of Robert Curthose, Principal=Robert II de Bellême4 |

| Event-Misc* | circa 1093 | William de Warenne fought unsuccessfully to marry Maud, daughter of Malcolm III Canmore, Principal=Matilda of Scotland4 |

| Event-Misc* | 3 September 1101 | Windsor, He was with Henry I4 |

| Event-Misc | 1103 | He supported Robert Curthose, and had his English properties confiscated. Robert prevailed upon Henry to restore them4 |

| (Henry) Battle-Tinchebray | 28 September 1106 | Tinchebray, Normandy, France, Principal=Henry I Beauclerc, Principal=Robert III Curthose8,9 |

| Event-Misc | 1109 | Nottingham, He attended a Great Council4 |

| Event-Misc | 1111 | He served as a Judge in Normandy4 |

| Event-Misc | 1119 | He commanded a division of the royal army at the battle of Bremule4 |

| Event-Misc | 1131 | Northampton, He attended the Council4 |

| (Witness) Death | 1 December 1135 | Angers, Maine-et-Loire, France, Principal=Henry I Beauclerc10,3,11 |

| Event-Misc | Easter 1136 | Westminster, He was with King Stephen4 |

Family | Isabel de Vermandois b. 1081, d. 13 Feb 1131 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 23 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 83-24.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 50-24.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 259.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 18.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 266.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S348] Wikipedia, online http://en.wikipedia.org/

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 164.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 1-23.

- [S232] Don Charles Stone, Ancient and Medieval Descents, 11-2.

William de Warenne1

William de Warenne1

M, #3007, d. 24 June 1088

| Father* | Rodulf de Warenne2,3 b. c 998 | |

| Mother* | Beatrix de Crepon2 | |

| Mother | Emma de St. Martin3 | |

William de Warenne|d. 24 Jun 1088|p101.htm#i3007|Rodulf de Warenne|b. c 998|p140.htm#i4181|Beatrix de Crepon||p319.htm#i9568|||||||Anonymous de Crepon||p319.htm#i9567|||| | ||

| Marriage* | Bride=Gundred (?)1,4 | |

| Death* | 24 June 1088 | Lewes, Surrey, England, |as a result of a wound suffered at Pevensey1,2,3 |

| Burial* | Lewes, |beside his first wife3 | |

| DNB | Warenne, William (I) de, first earl of Surrey [Earl Warenne] (d. 1088), magnate, was among the inner circle of Norman lords of Duke William's generation whose campaigns over some forty years consolidated the duchy and conquered England. Background and early career William's father, Rodulf or Ralph de Warenne (d. in or after 1074), was a minor Norman magnate with lands near Rouen and in the Pays de Caux, and William's earlier ancestry has long been debated. In the twelfth century the Warennes were believed to be descended from a niece of Gunnor, the wife of Duke Richard (I) of Normandy (d. 996) and the person seen as the linchpin of the wider ducal kin. He was certainly related in some way to them, since Anselm, archbishop of Canterbury, later prohibited the proposed marriage of his son William (II) de Warenne to a bastard daughter of Henry I on the grounds of their blood relationship. The most likely interpretation of the fragmentary evidence is that either William (I)'s mother or his paternal grandmother was Duchess Gunnor's niece Beatrice. Probably in his father's time the family adopted a surname from the village of Varenne, on the river of that name inland from Dieppe. William owed his eventual standing more to his own capabilities than to family connections or inherited wealth. By the mid 1050s, though still young, he was capable and experienced enough to be given joint command of a Norman army. His first recorded military action, during a period in which the Normans were constantly at war, was in the Mortemer campaign of 1054, as one of the leaders of the army which defeated the French. His reward was a swathe of lands which had belonged to his disgraced kinsman Roger (I) de Mortimer. Although some of the lands were soon restored to the Mortimers, William kept the important castles at Mortemer and Bellencombre. The latter, less than a day's ride from Varenne, became the capital of the Warenne estates in Normandy. At almost the same time he was further rewarded with lands confiscated in 1053 from William, count of Arques. The continuing confidence with which the duke regarded him kept William at the forefront of Norman affairs over the next two decades, and he was among those consulted when the expedition to England in 1066 was planned. Service and rewards in England William de Warenne is among the handful of Normans known for certain to have fought at Hastings, and in 1067 was one of four men left in charge in England when the king returned to Normandy. His role as a military commander continued to be important for another twenty years, suggesting a physical constitution as robust as the king's. In 1075 he and Richard de Clare were delegated to deal with the rebellion of Earl Ralph de Gael of East Anglia. The two first summoned the earl to attend the king's court to answer for an act of defiance, then mustered an army which defeated the rebels at Fawdon in south Cambridgeshire, mutilating their prisoners after the battle. Ralph retreated to Norwich, where Warenne and Clare began a siege which lasted three months but failed to prevent the earl's escape by boat. In the early 1080s William campaigned with the king's forces in Maine. William de Warenne's rewards in England were very large, elevating him into the first rank of the magnates. By 1086 he was the fourth richest tenant-in-chief, surpassed only by the king's half-brothers and his long-standing comrade and kinsman Roger de Montgomery. Such riches were accumulated over the course of the reign. The earliest acquisitions were presumably in Sussex, where he held the rape of Lewes, one of the five territories into which the shire was divided. The town of Lewes, a flourishing port on a tidal estuary, was divided between William and the king. One or the other built a castle there which became the capital of the Warenne lands in England. The original castle may have lain south of the town, where William is known to have reconstructed the church of St Pancras, and where a large mound may represent the motte. If that was the first site, it was abandoned in the 1070s when Warenne founded a priory there around the existing church. He would then have built the present castle north of the town, remarkable for having two mottes, one at each end of the bailey. The rape of Lewes as first created for William de Warenne may have stretched from the River Adur on the west to the River Ouse on the east, and indeed beyond the Ouse at its northern extremity. Before 1073, however, the rapes were reorganized. A new rape west of Lewes was created for William (I) de Briouze, to whom Warenne surrendered seventeen manors. On the east, twenty-eight manors in four hundreds beyond the Ouse were transferred to the count of Mortain's rape of Pevensey. In compensation for those losses Warenne received lands in East Anglia. William's second acquisition may have been the large estate of Conisbrough in Yorkshire, an important manor which occupied the gap between the marshes at the head of the Humber estuary and the Pennine foothills, and commanded the fords where the main road north crossed the River Don. Conisbrough was an old royal manor which had belonged to Earl Harold, and it seems likely that it was transferred to Warenne during the campaign against the English rebels at York in 1068. Far more important than Conisbrough, and overshadowing even the rape of Lewes in 1086, were William's lands in eastern England. In Norfolk, especially the west of the county, he was the largest landowner in a large and wealthy shire, and his manors there were complemented by others which spilled over the county boundary and through the western side of Suffolk and Essex as far as the Thames estuary and reached into south-east Cambridgeshire. The centre was at Castle Acre, where Warenne built not a castle but a large stone manor house (it was fortified only in the twelfth century). The estates in those four eastern shires were clearly acquired in stages. Some had belonged to Earl Harold and might have been handed over soon after 1066. Another group, before the conquest the possessions of a thegn called Toki, had fallen first to Warenne's Flemish brother-in-law Frederic, and after Frederic's death in 1070 came to William through his wife. He may not have controlled them directly until she died in 1085. Others seem to have been given to him in the aftermath of the 1075 rebellion, while the series of exchanges for parts of the original rape of Lewes may still have been going on in the 1080s. Estates and their management In 1086 the eastern shires accounted for half the value of Warenne's estate (more than half of that being in Norfolk), and Sussex two fifths. The other tenth, which included Conisbrough, was scattered about the country in little parcels: a single manor in Hampshire, another in Buckinghamshire, Kimbolton and its outliers in Huntingdonshire and Bedfordshire, a couple of estates on the Thames near Wallingford, two small manors in south Lincolnshire, some fishermen in Wisbech. The rationale for their dispersal is not easy to discern, and it may be wrong to look for any single all-inclusive purpose. Several besides Conisbrough had belonged to Earl Harold, including Kimbolton and the Lincolnshire manors; indeed outside Wessex only Warenne and Hugh d'Avranches, earl of Chester, were given Harold's property. At least one of the manors furthest from William's bases in Sussex and Norfolk had strategic importance: his Hampshire property was Fratton on Portsea Island, watching the entrance to Portsmouth harbour. William's dispositions of his landed estate suggest that he was a good organizer greedy for further spoils. Almost everywhere except Sussex he pushed at the limits of what he had been given, testing what more he could either claim legitimately, or simply take without opposition. Some of his extra acquisitions were peaceful enough, like the large manor of Whitchurch in Shropshire, which his distant cousin Roger de Montgomery gave him. But others were not. In Norfolk especially he asserted his lordship over freemen who might or might not have been assigned to him, leading to the many counterclaims and disputes recorded in Domesday Book. He was active even in shires where he was far less powerful. In Essex he stole land from the bishop of Durham and the abbot of Ely, and in Sussex from the nuns of Wilton; in Yorkshire he was at loggerheads with several of his neighbours about what properties were sokelands of Conisbrough; in Bedfordshire he won over the English thegn Augi from the Norman lord to whom the king had assigned him, and when Augi died took control of land which ought perhaps have gone to Augi's lord's successor; in Huntingdonshire in 1086 he staked some sort of a claim to a manor held by Hugh de Bolbec. Warenne was wealthy enough not to need to concentrate his resources in just one or two parts of the country, and the pattern of demesne estates which he created after granting others to his men had the deliberate effect of accentuating its dispersal and shifting the balance towards Sussex rather than Norfolk. Whereas the ratios of manorial values in 1086 over the honour as a whole, between eastern England, Sussex, and the rest, were 49:41:10, what William chose to retain in his own hands was balanced 33:48:20. In Sussex he kept only four manors, but far and away the four largest, whereas in Norfolk he was not so choosy. Elsewhere he retained under his direct control one manor in each of Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire, the core of Kimbolton, and all of Conisbrough. William's options may have been constrained by a lack of close lieutenants to whom he was willing to give a great deal of land and authority. Despite his gains in Normandy in the 1050s his lands there were not very extensive, and he did not succeed to any part of his paternal inheritance until at least the mid-1070s. His father was still alive in 1074 and there was an older brother, Rodulf or Ralph, who inherited probably the greater part of their father's estates. Some of William's tenants in England, including the ancestors of the families of Cailly, Chesney, Grandcourt, Pierrepont, Rosay, and Wancy, can be traced back to fiefs around his Norman capital of Bellencombre, but they were only a small minority of the fifty or more men to whom William gave lands. Some others were perhaps his Norman kinsmen: Tezelin and Lambert, for instance, had unusual forenames which are known to have been used in other branches of Beatrice's family. Only a handful of his leading men held in both the eastern counties and the rape of Lewes, and the wealth which William had at his disposal was widely distributed. Warenne's vigour in running his estates is evident from improvements in their economic condition. It seems that he took an interest in running his manors not just efficiently but aggressively, and that he was good at choosing capable reeves and bailiffs. Conisbrough was well stocked with ploughteams and intensively cultivated by Yorkshire standards, and, almost uniquely in a county devastated by warfare, more than doubled in value between 1066 and 1086. Values on the four demesne manors in Sussex also went up sharply after William acquired them, and at Castle Acre he more than tripled the size of his sheep flock. Foundation of Lewes Priory Despite an evil reputation at Ely, where it was later believed, or at any rate hoped, that Warenne's departing soul had been claimed by demons, William was at least conventionally pious. The story of the foundation of Lewes Priory by William and his wife, Gundrada de Warenne (d. 1085), was preserved there only in much later traditions, but in essence it is believable. Probably at an early stage William consulted Archbishop Lanfranc of Canterbury. Later, William and Gundrada went on pilgrimage to Rome, but reached no further than the great Burgundian abbey of Cluny because of the war in Italy between the pope and the emperor. Their journey probably took place within the period 1081–3 rather than at the date of 1077 assigned to it elsewhere. At Cluny the couple were received into the fellowship of the monks and resolved to found an English priory following the rule of Cluny. After difficulties and one false start, it was accomplished under a prior and three monks sent from Cluny. The monastery was established around the existing church of St Pancras in the suburbs of Lewes, it was well endowed, and an ambitious building programme was put in train. Lewes was the first house of Cluniac monks in England and the precursor of several others, and the importance of the Warennes' role in their arrival needs to be stressed. William clearly regarded Lewes Priory as his spiritual home, and had both Gundrada and himself buried there. It was also a focus for the spiritual aspirations of his men, at least one of whom entered the priory as a monk and donated the manor which he had held as William's tenant. When he died, William was planning to establish a second priory at Castle Acre, a project brought to fruition by his son William (II). Earldom, death, and family In the turmoil which enveloped England after the death of William the Conqueror in September 1087, William de Warenne stood firm by William Rufus. His reward, some time between Christmas 1087 and the end of March 1088, was the titular earldom of Surrey and very probably three valuable Surrey manors, Reigate, Dorking, and Shere. Warenne fought for the king during the invasion of England by supporters of Robert Curthose and was wounded by an arrow during the siege of Pevensey Castle in spring 1088. He was carried to Lewes and died there of his wounds on 24 June. William's first wife was the Flemish noblewoman Gundrada, whom he married c.1066. They had at least three children and she died in childbirth in 1085. He then married a sister, name unknown, of Richard Gouet, a landowner in the Perche region. Her attempt to make restitution for the damage which he had inflicted upon Ely Abbey by a gift of 100 shillings a few days after his death was refused by the monks. William's elder son, William (II), succeeded him in England and Normandy; his younger son Reynold inherited Gundrada's Flemish lands. A nephew, Roger, son of Erneis, was first a knight in the household of Earl Hugh of Chester and later a monk of St Evroult, where he told the historian Orderic Vitalis much about the family. William's remains were reburied in a leaden chest at Lewes Priory during rebuilding there c.1145, from where they were disinterred during railway construction in 1845. In 1847 they were placed alongside Gundrada's remains in the parish church of St John, Southover, in Lewes, where they still rest. C. P. Lewis Sources W. Farrer and others, eds., Early Yorkshire charters, 12 vols. (1914–65), vol. 8 · GEC, Peerage, new edn, 12/1.492–5 · L. C. Loyd, ‘The origin of the family of Warenne’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 31 (1932–4), 97–113 · K. S. B. Keats-Rohan, ‘Aspects of Robert of Torigny's genealogies revisited’, Nottingham Medieval Studies, 37 (1993), 21–7 · A. Farley, ed., Domesday Book, 2 vols. (1783) · J. F. A. Mason, William the first and the Sussex rapes (1966) · P. Dalton, Conquest, anarchy, and lordship: Yorkshire, 1066–1154, Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought, 4th ser., 27 (1994), 33–4, 64–5 · B. Golding, ‘The coming of the Cluniacs’, Anglo-Norman Studies, 3 (1980), 65–77, 208–12 · D. J. C. King, Castellarium Anglicanum: an index and bibliography of the castles in England, Wales, and the islands, 2 (1983), 306, 472 · C. P. Lewis, ‘The earldom of Surrey and the date of Domesday Book’, Historical Research, 63 (1990), 329–36 · L. C. Loyd, The origins of some Anglo-Norman families, ed. C. T. Clay and D. C. Douglas, Harleian Society, 103 (1951) · Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist. · E. Edwards, ed., Liber monasterii de Hyda, Rolls Series, 45 (1866), 283–321 · B. Dickins, ‘Fagaduna in Orderic (AD 1075)’, Otium et negotium: studies in onomatology and library science presented to Olof von Feilitzen, ed. F. Sandgren (1973), 44–5 © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press C. P. Lewis, ‘Warenne, William (I) de, first earl of Surrey (d. 1088)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/28736, accessed 24 Sept 2005] William (I) de Warenne (d. 1088): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/287365 | |

| Event-Misc* | after 1054 | He was given the castle of Moremer by Duke William, as Roger de Mortemer had forfeited it at the battle of Moremer in Feb 10546 |

| (William) Battle-Hastings | 14 October 1066 | Hastings, Sussex, England, Principal=William I of Normandy "the Conqueror", Principal=Harold II Godwinson7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 |

| Event-Misc* | 1075 | Richard FitzGilbert and William de Warenne were regents of England, and crushed the rebellion of the Dukes of Hereford and Norfolk, Principal=Richard FitzGilbert15 |

| Event-Misc | between 1078 and 1082 | He founded Lewes Priory as a cell of Cluny6 |

| Event-Misc | between 1083 and 1085 | He fought for the King in Maine6 |

Family | Gundred (?) b. c 1051, d. 27 May 1085 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 83-24.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 266.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 158-1.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 259.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 50-23.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 270-24.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 42.

- [S285] Leo van de Pas, 30 Jun 2004.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 89.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 38.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 94.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 142.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 51, 259.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 50-24.

Gundred (?)1

F, #3008, b. circa 1051, d. 27 May 1085

| Father* | Gerbod of St. Omer2,3 | |

| Mother* | Maud of Flanders2 b. 1032, d. 3 Nov 1083 | |

Gundred (?)|b. c 1051\nd. 27 May 1085|p101.htm#i3008|Gerbod of St. Omer||p150.htm#i4475|Maud of Flanders|b. 1032\nd. 3 Nov 1083|p59.htm#i1769|||||||Count Baldwin V. of Flanders|b. 1013\nd. 1 Sep 1067|p148.htm#i4438|Adèle of France|b. c 1003\nd. 8 Jan 1079|p148.htm#i4439| | ||

| Marriage* | 1st=William de Warenne1,3 | |

| Birth* | circa 1051 | Normandy, France2 |

| Death* | 27 May 1085 | Castle Acre, Norfolk, England, |in childbirth2,3,4 |

| Burial* | Chapter House, Lewes4 | |

| DNB | Warenne, Gundrada de (d. 1085), noblewoman, was the daughter of Gerbod, head of a noble Flemish family who was hereditary advocate of the important monastery of St Bertin. She had brothers called Gerbod and Frederic, and the family were players in the politics of the marcher counties between Flanders and Normandy. In 1067, for example, Frederic, alongside the count of Flanders, witnessed a charter of Count Guy of Ponthieu in favour of the abbey of St Riquier in the Somme valley. They may also have been involved in England before 1066, when, intriguingly a Frederic and a Gundrada between them held four manors fairly close to one another in Sussex and Kent. The names Frederic and Gundrada were certainly not English. Since Sussex was where Gundrada's husband was later given his most important lands in England, their presence before the conquest is plausibly explained as the result of Anglo-Flemish ties predating 1066. Gundrada married the Norman baron William (I) de Warenne (d. 1088), whose lands lay towards Flanders; their eldest son was William (II) de Warenne; a second son was old enough to command troops in 1090, so the marriage probably lay within a few years either side of 1066. Warenne, already an important figure in Normandy, was a major beneficiary of the conquest and both his brothers-in-law also joined the expedition to England. Frederic seems to have been rewarded with the lands of a rich Englishman called Toki in Norfolk, Suffolk, and Cambridgeshire, worth over £100 a year, but was killed in 1070 during the rebellion of Hereward the Wake in the Fens. His estates were assigned to Gundrada and her husband, and the fact that they were still known in 1086 as ‘Frederic's fief’ suggests that Gundrada retained control of them during her lifetime. One small manor among them belonged in 1086 to the abbey of St Riquier, perhaps Gundrada's gift in memory of her brother. The other brother, Gerbod, was appointed by King William to a difficult military command in Chester, and may even have been given the title of earl. Probably in late 1070 he gave up his position in England and returned to Flanders to safeguard his interests there, rendered uncertain by the civil war which broke out on the death of the count. Reports of his fate in Flanders are contradictory. Fifty years after the event, one opinion was that he was killed, another that he fell into the hands of his enemies and was imprisoned. More attractive than either is the possibility that he was the Gerbod who accidentally killed his lord, young Count Arnulf, at the battle of Kassel in February 1071, travelled in penance to Rome, and ended as a monk of Cluny. A family connection with Cluny would provide a clear context for Gundrada and William de Warenne's later visit to the monastery and their foundation of a Cluniac priory at Lewes, probably in the early 1080s. The priory's valuable endowments in Norfolk came from what had been Frederic's lands. Gerbod's property in Flanders evidently passed to Gundrada, and her interest in the abbey of St Bertin was inherited by her younger son Reynold de Warenne. Gundrada died in childbirth at Castle Acre on 27 May 1085 and was buried in the chapter house of Lewes Priory. On the consecration of new monastic buildings c.1145, her bones were placed in a leaden chest under a magnificent tombstone of black Tournai marble, richly carved in the Romanesque style, with foliage and lions' heads, by a sculptor who later worked for Henry de Blois, bishop of Winchester and himself trained at Cluny. The tombstone was moved after the dissolution of Lewes Priory to Ifield church in Sussex, and in 1774 to the parish church of St John, Southover, in Lewes, where it still survives. Two leaden chests containing the remains of Gundrada and William were rediscovered in 1845 and placed in Southover church in 1847. C. P. Lewis Sources W. Farrer and others, eds., Early Yorkshire charters, 12 vols. (1914–65), vol. 8 · GEC, Peerage, new edn, 12/1.494 · G. Zarnecki, J. Holt, and T. Holland, eds., English romanesque art, 1066–1200 (1984), 181–2 [exhibition catalogue, Hayward Gallery, London, 5 April–8 July 1984] · C. P. Lewis, ‘The formation of the honor of Chester, 1066–1100’, Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society, 71 (1991), 37–68, esp. 38–9 [G. Barraclough issue, The earldom of Chester and its charters, ed. A. T. Thacker] · E. Warlop, The Flemish nobility before 1300, 4 vols. (1975–6), 2/2.1024 · B. Golding, ‘The coming of the Cluniacs’, Anglo-Norman Studies, 3 (1980), 65–77, 208–12 · A. Farley, ed., Domesday Book, 2 vols. (1783) · Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist. · E. A. Freeman, ‘The parentage of Gundrada, wife of William of Warren’, EngHR, 3 (1888), 680–701 © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press C. P. Lewis, ‘Warenne, Gundrada de (d. 1085)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/11736, accessed 24 Sept 2005] Gundrada de Warenne (d. 1085): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/117365 | |

| DNB* | Warenne, Gundrada de (d. 1085), noblewoman, was the daughter of Gerbod, head of a noble Flemish family who was hereditary advocate of the important monastery of St Bertin. She had brothers called Gerbod and Frederic, and the family were players in the politics of the marcher counties between Flanders and Normandy. In 1067, for example, Frederic, alongside the count of Flanders, witnessed a charter of Count Guy of Ponthieu in favour of the abbey of St Riquier in the Somme valley. They may also have been involved in England before 1066, when, intriguingly a Frederic and a Gundrada between them held four manors fairly close to one another in Sussex and Kent. The names Frederic and Gundrada were certainly not English. Since Sussex was where Gundrada's husband was later given his most important lands in England, their presence before the conquest is plausibly explained as the result of Anglo-Flemish ties predating 1066. Gundrada married the Norman baron William (I) de Warenne (d. 1088), whose lands lay towards Flanders; their eldest son was William (II) de Warenne; a second son was old enough to command troops in 1090, so the marriage probably lay within a few years either side of 1066. Warenne, already an important figure in Normandy, was a major beneficiary of the conquest and both his brothers-in-law also joined the expedition to England. Frederic seems to have been rewarded with the lands of a rich Englishman called Toki in Norfolk, Suffolk, and Cambridgeshire, worth over £100 a year, but was killed in 1070 during the rebellion of Hereward the Wake in the Fens. His estates were assigned to Gundrada and her husband, and the fact that they were still known in 1086 as ‘Frederic's fief’ suggests that Gundrada retained control of them during her lifetime. One small manor among them belonged in 1086 to the abbey of St Riquier, perhaps Gundrada's gift in memory of her brother. The other brother, Gerbod, was appointed by King William to a difficult military command in Chester, and may even have been given the title of earl. Probably in late 1070 he gave up his position in England and returned to Flanders to safeguard his interests there, rendered uncertain by the civil war which broke out on the death of the count. Reports of his fate in Flanders are contradictory. Fifty years after the event, one opinion was that he was killed, another that he fell into the hands of his enemies and was imprisoned. More attractive than either is the possibility that he was the Gerbod who accidentally killed his lord, young Count Arnulf, at the battle of Kassel in February 1071, travelled in penance to Rome, and ended as a monk of Cluny. A family connection with Cluny would provide a clear context for Gundrada and William de Warenne's later visit to the monastery and their foundation of a Cluniac priory at Lewes, probably in the early 1080s. The priory's valuable endowments in Norfolk came from what had been Frederic's lands. Gerbod's property in Flanders evidently passed to Gundrada, and her interest in the abbey of St Bertin was inherited by her younger son Reynold de Warenne. Gundrada died in childbirth at Castle Acre on 27 May 1085 and was buried in the chapter house of Lewes Priory. On the consecration of new monastic buildings c.1145, her bones were placed in a leaden chest under a magnificent tombstone of black Tournai marble, richly carved in the Romanesque style, with foliage and lions' heads, by a sculptor who later worked for Henry de Blois, bishop of Winchester and himself trained at Cluny. The tombstone was moved after the dissolution of Lewes Priory to Ifield church in Sussex, and in 1774 to the parish church of St John, Southover, in Lewes, where it still survives. Two leaden chests containing the remains of Gundrada and William were rediscovered in 1845 and placed in Southover church in 1847. C. P. Lewis Sources W. Farrer and others, eds., Early Yorkshire charters, 12 vols. (1914–65), vol. 8 · GEC, Peerage, new edn, 12/1.494 · G. Zarnecki, J. Holt, and T. Holland, eds., English romanesque art, 1066–1200 (1984), 181–2 [exhibition catalogue, Hayward Gallery, London, 5 April–8 July 1984] · C. P. Lewis, ‘The formation of the honor of Chester, 1066–1100’, Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society, 71 (1991), 37–68, esp. 38–9 [G. Barraclough issue, The earldom of Chester and its charters, ed. A. T. Thacker] · E. Warlop, The Flemish nobility before 1300, 4 vols. (1975–6), 2/2.1024 · B. Golding, ‘The coming of the Cluniacs’, Anglo-Norman Studies, 3 (1980), 65–77, 208–12 · A. Farley, ed., Domesday Book, 2 vols. (1783) · Ordericus Vitalis, Eccl. hist. · E. A. Freeman, ‘The parentage of Gundrada, wife of William of Warren’, EngHR, 3 (1888), 680–701 © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press C. P. Lewis, ‘Warenne, Gundrada de (d. 1085)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/11736, accessed 23 Sept 2005] Gundrada de Warenne (d. 1085): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11736 Back to top of biography Site credits5 | |

| Name Variation | Gundred of England Warren2 |

Family | William de Warenne d. 24 Jun 1088 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Sir John FitzAlan1

M, #3009, b. May 1223, d. before 10 November 1267

|

| Father* | John FitzAlan2,3,4,5 b. c 1164, d. Mar 1240 | |

| Mother* | Isabel d' Aubigny2,3,4,5 b. c 1203 | |

Sir John FitzAlan|b. May 1223\nd. b 10 Nov 1267|p101.htm#i3009|John FitzAlan|b. c 1164\nd. Mar 1240|p101.htm#i3013|Isabel d' Aubigny|b. c 1203|p101.htm#i3012|William FitzAlan|d. c 1210|p140.htm#i4186|(?) FitzHenry||p140.htm#i4187|Sir William d' Aubigny|b. c 1165\nd. 1 Feb 1220/21|p59.htm#i1756|Mabel of Chester|b. c 1172|p59.htm#i1757| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | May 1223 | Arundel, Essex, England3 |

| Marriage* | before 1245 | 1st=Maud le Boteler3,6,7 |

| Death* | before 10 November 1267 | 1,3,4 |

| DNB* | Fitzalan, John (II) (1223-1267), baron, was the son of John (I) Fitzalan (d. 1240) and his first wife, Isabel, the sister and coheir of Hugh d'Aubigny, earl of Arundel, who died in 1243 with no direct male heirs. John (II) Fitzalan married Maud (or Matilda), the daughter of Theobald le Botiller and his second wife, Rohese de Verdon. After his father's death in 1240 the Shropshire lordships of Oswestry and Clun were in the custody of John (III) Lestrange, sheriff of Shropshire and member of a family long friendly with the Fitzalans, until John (II) Fitzalan came of age in 1244. After the death of Hugh d'Aubigny in 1243 a quarter of Hugh's possessions, including the castle and manor of Arundel, were awarded to Fitzalan in the right of his mother. After he offered a relief of £1000 in May 1244 he took possession of Arundel and the family lands in Shropshire, including the castles at Clun, Oswestry, and Shrawardine. The Fitzalans had been important marcher barons since the mid-twelfth century and John (II) Fitzalan was a significant figure in both national politics and those of the Welsh marches. Henry III granted him permission in July 1253 to pledge his lands for 500 marks to cover costs of accompanying the king in Gascony. In 1255 and 1256 Fulk (IV) Fitzwarine, lord of Whittington (just north of Oswestry), complained of attacks by Fitzalan's men. In August 1258 his men from Clun attacked Bishops Castle (Lydbury North), a large Shropshire manor belonging to the bishops of Hereford. His military power was so important that in August 1257 he was appointed captain for the custody of the march north of Montgomery, and in March 1258 was ordered to lead his men to Chester to participate in an expedition against Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. In 1259 he was one of eight royal negotiators sent to Montgomery Ford to settle breaches of the truce with Llywelyn. The latter complained in 1262 about raids on Bromfield by Fitzalan, Roger (III) de Mortimer, and John Lestrange. The marcher barons were a major focus of opposition to Henry III and Fitzalan adhered to this party from late 1258. By June 1263 he and his son John (III) were both active supporters of Simon de Montfort and in that month a group including Fitzalan, Roger Clifford, Humphrey (V) de Bohun, and Hamo L'Estrange attacked and captured the Poitevin royalist bishop of Hereford, Peter d'Aigueblanche. On 12 July Fitzalan seized Bishops Castle, which the family refused to surrender for over six years. By late autumn the Lord Edward had won Fitzalan over to the royal side; on 24 December he was appointed as one of five keepers of the peace for Shropshire and Staffordshire, figures whose task it was to wrest administrative control of these counties from the baronially controlled sheriff. In January 1264 he was the eighth baron who swore to adhere to the agreement under which the king of France would arbitrate between Henry III and his barons. After being besieged with Earl Warenne in Rochester Castle, Fitzalan fought in the royal army and was captured at the battle of Lewes on 14 May. In April 1265 Montfort's government suspected his loyalty and ordered him to surrender either his son or Arundel Castle. After Montfort's defeat Fitzalan was appointed on 18 April 1266 as keeper and defender of Sussex to help the sheriff arrest disturbers of the peace. In January 1267 he was ordered to investigate and quell treasonous plots in Sussex. He died in November 1267, having ordered his body to be buried in Haughmond Abbey, Shropshire; his second wife outlived him. He was succeeded by his son John (III) Fitzalan (1245–1272/3), who married Isabel de Mortimer and was succeeded in turn by his son Richard (I) Fitzalan. Although Rishanger called John (II) Fitzalan earl of Arundel in 1264 and some modern scholars have occasionally followed this style, he did not apparently use this title. In 1258 he was called lord of Arundel and in 1266 John Fitzalan de Arundel. Frederick Suppe Sources I. J. Sanders, English baronies: a study of their origin and descent, 1086–1327 (1960) · D. C. Roberts, ‘Some aspects of the history of the lordship of Oswestry to 1300 AD’, MA diss., U. Wales, 1934 · R. W. Eyton, Antiquities of Shropshire, 12 vols. (1854–60) · F. Suppe, Military institutions on the Welsh marches: Shropshire, 1066–1300 (1994) · J. E. Lloyd, A history of Wales from the earliest times to the Edwardian conquest, 2 vols. (1911) · J. Meisel, Barons of the Welsh frontier … 1066–1272 (1980) · T. F. Tout, ‘Wales and the March during the Barons’ War’, Collected papers of Thomas Frederick Tout, ed. F. M. Powicke, 2 (1934), 47–100 · R. F. Treharne, The baronial plan of reform, 1258–1263, [new edn] (1971) · GEC, Peerage · CIPM, vol. 1 · R. F. Treharne and I. J. Sanders, eds., Documents of the baronial movement of reform and rebellion, 1258–1267 (1973) · Willelmi Rishanger … chronica et annales, ed. H. T. Riley, pt 2 of Chronica monasterii S. Albani, Rolls Series, 28 (1865) · DNB Wealth at death wealthy © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Frederick Suppe, ‘Fitzalan, John (II) (1223-1267)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/9531, accessed 24 Sept 2005] John (II) Fitzalan (1223-1267): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/95318 | |

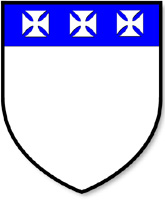

| Arms* | Gu. A lion rampant or (Glover).5 | |

| Event-Misc | 27 November 1243 | He was awarded the Castle and Honour of Arundel by right of his mother9 |

| Event-Misc* | 11 June 1259 | Commissioner re truce with Llewellyn ap Griffin5 |

| Event-Misc | 24 December 1263 | He was made a Keeper of Salop and Staff.5 |

| (Henry) Battle-Lewes | 14 May 1264 | The Battle of Lewes, Lewes, Sussex, England, when King Henry and Prince Edward were captured by Simon of Montfort, Earl of Leicester. Simon ruled England in Henry's name until his defeat at Evesham, Principal=Henry III Plantagenet King of England, Principal=Simon VI de Montfort10,11,12,13,14,15 |

| Event-Misc | 18 September 1264 | He and others are to besiege Pevensey Castle and capture the King's enemies.5 |

| Event-Misc* | 26 April 1265 | Mandate to Simon de Montfort, s. of E. of Leicester, to take security from Jn. Fitz Alan, who is under suspicion, viz. either his son as hostage or Arundel Castle. Mandate to John to deliever one or the other to Simon., Principal=Simon VI de Montfort5 |

| Event-Misc | 18 April 1266 | He is made keeper of of Suss., he is to stay there and arrest disturbers5 |

| Will* | October 1267 | 1,7 |

| Feudal* | 10 November 1267 | at the time of his Inq., 5 Kt. Fees in Suss., and lands at Oswestry, etc., and Salop.16 |

Family | Maud le Boteler b. c 1225, d. 27 Nov 1283 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 149-28.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 149-27.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 134-3.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 2, p. 29.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 71-29.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 110.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 86.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 4.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 5, p. 10.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Fitz Alan 7.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 21.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 218.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 34.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 2, p. 30.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cornwall 5.

Maud le Boteler1

F, #3010, b. circa 1225, d. 27 November 1283

| Father* | Theobald Butler2,3 b. 1200, d. 19 Jul 1230 | |

| Mother* | Rohese de Verdun1,3 b. c 1200, d. b 22 Feb 1246 | |

Maud le Boteler|b. c 1225\nd. 27 Nov 1283|p101.htm#i3010|Theobald Butler|b. 1200\nd. 19 Jul 1230|p89.htm#i2665|Rohese de Verdun|b. c 1200\nd. b 22 Feb 1246|p89.htm#i2664|Theobald FitzWalter|b. c 1160\nd. bt 4 Aug 1205 - 14 Feb 1206|p140.htm#i4200|Maud le Vavasour|b. c 1187\nd. b 1226|p141.htm#i4201|Nicholas de Verdun|b. c 1174\nd. Apr 1232|p101.htm#i3011|Joan de Lacy|b. c 1178|p141.htm#i4202| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | circa 1225 | of Lincoln, Lincolnshire, England3 |

| Marriage | before 1245 | Groom=Sir John FitzAlan3,4,5 |

| Marriage* | circa 28 August 1283 | Livery to Ric. de Amundevill and w. Matilda, wid. of Jn. Fitz Alan, a Kt. Fee at Jaye, Salop, which Walter de Jay, dec., held of said John, and wh. was assigned to Matilda in dower of John's Kt. Fees., Groom=Richard de Amundevill6,7 |

| Death* | 27 November 1283 | 1,3 |

| Event-Misc* | 5 July 1281 | She holds in dower part of Arundel Forest6 |

Family | Sir John FitzAlan b. May 1223, d. b 10 Nov 1267 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 29 May 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 149-28.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 134-3.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 71-29.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 110.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 2, p. 30.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 86.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cornwall 5.

Nicholas de Verdun1

M, #3011, b. circa 1174, d. April 1232

| Father* | Bertram de Verdon2,3 d. 1192 | |

| Mother* | Roesia (?)2 d. 1215 | |

Nicholas de Verdun|b. c 1174\nd. Apr 1232|p101.htm#i3011|Bertram de Verdon|d. 1192|p141.htm#i4216|Roesia (?)|d. 1215|p141.htm#i4217|Norman de Verdun|b. c 1050\nd. a 1133|p353.htm#i10581|Lasceline de Clinton|b. c 1118|p141.htm#i4219||||||| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1174 | 2 |

| Marriage* | Principal=Joan de Lacy2 | |

| Marriage* | Principal=Clemencia (?)4 | |

| Death* | April 1232 | 2 |

| (Witness) Biography | Dugdale felt that this family was related to the Verdons. They had similar arms (fretty) and Henry had received an inheritance from Nicholas de Verdon. Henry was a favorite of Ranulph, Earl of Chester, one of the most powerful barons in England, and received from him Newhall in Cheshire, as well as manors in Staffordshire. From King John, in reward for his support in the baronial insurrections, he received royal grant of the lordship of Storton in Warwickshire. He executed the office of sheriff of Salop and Staffordshire for Ranulf of Chester and later was named to those offices in his own right in 10 Hen III. He also received grants in Ireland from Hugh de Lacy, Earl of Ulster. When Richard Marshall rebelled and made an incursion into Wales, Henry III seized Henry de Audley along with other marcher barons. Later, Henry was made governor of Shrewsbury, the castles of Chester and Beeston, and Newcastle-under-Lyme., Principal=Henry de Audley5 | |

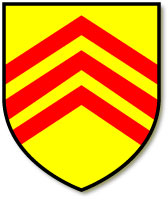

| Arms* | Sealed: early 13th cent.: Fretty, with pellets in the spaces (Birch).6 | |

| Name Variation | Nicholas de Verdon2 | |

| Residence* | Alton, Staffordshire, England1 |

Family | Joan de Lacy b. c 1178 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Apr 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 149-28.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 255.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 71-28.

- [S342] Sir Bernard Burke, Extinct Peerages, p. 15.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 5, p. 104.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, II - 448.

Isabel d' Aubigny1

F, #3012, b. circa 1203

| Father* | Sir William d' Aubigny b. c 1165, d. 1 Feb 1220/21; daughter and coheir2,3,4,5,6 | |

| Mother* | Mabel of Chester2,3 b. c 1172 | |

Isabel d' Aubigny|b. c 1203|p101.htm#i3012|Sir William d' Aubigny|b. c 1165\nd. 1 Feb 1220/21|p59.htm#i1756|Mabel of Chester|b. c 1172|p59.htm#i1757|Sir William d' Aubigny|b. c 1139\nd. 24 Dec 1193|p86.htm#i2565|Maud de St. Hilary|b. c 1132|p86.htm#i2566|Hugh of Kevelioc|b. 1147\nd. 30 Jun 1181|p59.htm#i1758|Bertrade de Montfort|b. 1155\nd. 1227|p97.htm#i2903| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=John FitzAlan1,3,4 | |

| Birth* | circa 1203 | 3 |

| Name Variation | Isabel de Albini3 |

Family | John FitzAlan b. c 1164, d. Mar 1240 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 29 May 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 149-27.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 149-26.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 134-2.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 6.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 2, p. 29.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 134-3.

John FitzAlan1

M, #3013, b. circa 1164, d. March 1240

|

| Father* | William FitzAlan2,3 d. c 1210 | |

| Mother* | (?) FitzHenry2 | |

| Father | William FitzAlan4 b. 1105, d. 1160 | |

John FitzAlan|b. c 1164\nd. Mar 1240|p101.htm#i3013|William FitzAlan|d. c 1210|p140.htm#i4186|(?) FitzHenry||p140.htm#i4187|William FitzAlan|b. 1105\nd. 1160|p140.htm#i4183|Isabel de Say||p140.htm#i4184|Henry I. Curtmantel|b. 5 Mar 1132/33\nd. 6 Jul 1189|p55.htm#i1622|Rosamond Clifford|d. 1177|p135.htm#i4030| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Isabel d' Aubigny1,2,5 | |

| Birth* | circa 1164 | of Arundel, Essex, England2 |

| Death* | March 1240 | 2,5,3 |

| Title* | Lord of Clun and Oswestry, Salop.3 |

Family | Isabel d' Aubigny b. c 1203 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 24 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 149-27.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 110.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 86.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 134-2.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 134-3.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 2, p. 29.

Richard de Clare "Strongbow"1

M, #3014, b. circa 1130, d. circa 20 April 1176

|

| Father* | Gilbert de Clare1,2 b. 1100, d. 6 Jan 1147/48 | |

| Mother* | Isabel de Beaumont3,2 b. c 1100 | |

Richard de Clare "Strongbow"|b. c 1130\nd. c 20 Apr 1176|p101.htm#i3014|Gilbert de Clare|b. 1100\nd. 6 Jan 1147/48|p101.htm#i3017|Isabel de Beaumont|b. c 1100|p101.htm#i3020|Gilbert FitzRichard de Clare|b. b 1066\nd. bt 1114 - 1117|p101.htm#i3018|Adeliza de Clermont|b. c 1074|p101.htm#i3019|Robert de Beaumont|b. 1049\nd. 5 Jun 1118|p92.htm#i2754|Isabel de Vermandois|b. 1081\nd. 13 Feb 1131|p64.htm#i1915| | ||

| Birth* | circa 1130 | Tunbridge, Kent, England1,2 |