Ralph Fulshurst

M, #1591

| Marriage* | as her second husband, Principal=Anne Chamberlayne1,2,3 | |

| Probate* | 1530 | mentions wife Anne and "my sonne Cope."2 |

| Name Variation | Ralph Foulshurst3 |

| Last Edited | 3 Jul 2004 |

Sir Edward Raleigh Knt.1

M, #1592, b. circa 1441, d. before 6 June 1513

| Father* | William Raleigh Esq.2,1,3,4 b. s 1420, d. 14 Oct 1460 | |

| Mother* | Elizabeth Greene5,6,3,4 b. c 1416 | |

Sir Edward Raleigh Knt.|b. c 1441\nd. b 6 Jun 1513|p54.htm#i1592|William Raleigh Esq.|b. s 1420\nd. 14 Oct 1460|p54.htm#i1599|Elizabeth Greene|b. c 1416|p54.htm#i1598|John Ralegh|b. c 1382|p54.htm#i1600|Idony Cotesford||p54.htm#i1601|Sir Thomas Greene Knt.|b. 10 Feb 1400\nd. 18 Jan 1461/62|p54.htm#i1602|Philippa de Ferrers||p54.htm#i1603| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | circa 1441 | 2,1,7 |

| Birth | circa 1442 | 8,9 |

| Marriage* | 1467 | Principal=Margaret Verney2,1,10,11,8,12 |

| Death* | before 6 June 1513 | 13,12 |

| Probate* | 6 June 1513 | 2,13,8 |

| Occupation | between 1461 and 1503 | Justice of the Peace1 |

| Occupation* | 1467 | Warwickshire, England, Sheriff of Warwickshire1,8 |

| Occupation | Sheriff of Leicestershire8 | |

| Residence* | Farnborough, Warwickshire, England7,8,12 | |

| Residence | Ilfracombe, Devonshire, England8,12 | |

| Will* | 20 June 1509 | refers to father William and mother Elizabeth. Requested burial in Chapel of Our Lady at Farnborough1,8,12 |

| Note | Birth place in question; may be Farneborough Warws. vs. Wrks., England? Death date: family group record indicates "will 20 JUN 1509" Info. sources: Marbury Ancestry A9A27, p. 37; B10B7, p. 173 |

Family | Margaret Verney b. c 1445 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 7 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 37.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-36.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 7.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 14.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-35.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-11.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-13.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 6.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 16.

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 16.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-12.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 15.

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 17.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-37.

Margaret Verney1

F, #1593, b. circa 1445

| Father* | Sir Ralph Verney M.P.2,1,3,4,5,6 b. c 1412, d. Jun 1478 | |

| Mother* | Emme (?)5,6 | |

Margaret Verney|b. c 1445|p54.htm#i1593|Sir Ralph Verney M.P.|b. c 1412\nd. Jun 1478|p54.htm#i1594|Emme (?)||p380.htm#i11383|Ralph Verney||p446.htm#i13365|||||||||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | circa 1445 | London, England |

| Marriage* | 1467 | Principal=Sir Edward Raleigh Knt.2,1,3,4,5,6 |

| Married Name | 1467 | Raleigh2,1 |

| Living* | 1509 | 6 |

Family | Sir Edward Raleigh Knt. b. c 1441, d. b 6 Jun 1513 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 3 Jul 2004 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 37.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-36.

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 16.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-12.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 6.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 15.

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 17.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-37.

Sir Ralph Verney M.P.

M, #1594, b. circa 1412, d. June 1478

| Father* | Ralph Verney1 | |

Sir Ralph Verney M.P.|b. c 1412\nd. Jun 1478|p54.htm#i1594|Ralph Verney||p446.htm#i13365|||||||||||||||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | circa 1412 | London, England |

| Marriage* | Principal=Emme (?)2,3 | |

| Marriage* | Principal=Eleanor Poole1 | |

| Death* | June 1478 | 4 |

| Apprenticed* | 1434 | London, Middlesex, England, He finished his apprenticeship to Thomas Faulconer, mercer.5 |

| Occupation | 1456 | City of London, England, Sheriff4 |

| Occupation | 1457 | Castle Baynard, City of London, England, Alderman4 |

| Occupation | 1459 | City of London, England, M.P. for London, 1459, 1469, 14724 |

| Occupation* | 1465 | London, England, Lord Mayor of London in 5 Edward IV6,7,2,3 |

| Occupation | City of London, England, a mercer4 | |

| Knighted* | 21 May 1471 | City of London, England4 |

| Will* | 11 June 1478 | 8 |

| Note* | This partial coalescence of the interests of the bourgeoisie and the landowners is excellently illustrated by the history of the Verney family. The founder of the line, the merchant Ralph Verney, became Lord Mayor of London in 1465. After the Battle of Tewkeshury which ended the Wars of the Roses, Edward IV knighted twelve citizens in testimony of gratitude to his supporters; among these, Verney stood first and received a grant of land.9 | |

| HTML* | Verney and Middle Claydon an estate Ralph Verney apparently purchased. British History Online |

Family 1 | ||

| Child | ||

Family 2 | Eleanor Poole | |

| Children |

| |

Family 3 | Emme (?) | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 5 Jul 2004 |

Citations

- [S285] Leo van de Pas, 30 Jun 2004.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 6.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 15.

- [S211] Rev. Alfred B. Beaven, Aldermen of the City of London.

- [S288] Sylvia Thrup, Merchant Class of Medieval London.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-36.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 37.

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 16.

- [S212] Aleksandr A. Smirnov, Shakespeare: A Marxist Interpretation.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-12.

Richard Chamberlayne

M, #1595, b. between 1436 and 1439, d. 28 August 1496

|

| Father* | Richard Chamberlayne1,2,3 b. 1391, d. 1439 | |

| Mother* | Margaret Knyvet1,2,4 b. c 1412, d. shortly before 12 May 1458 | |

Richard Chamberlayne|b. bt 1436 - 1439\nd. 28 Aug 1496|p54.htm#i1595|Richard Chamberlayne|b. 1391\nd. 1439|p56.htm#i1671|Margaret Knyvet|b. c 1412\nd. shortly before 12 May 1458|p56.htm#i1672|Sir Richard Chamberlayne|b. 1320\nd. 24 Aug 1396|p75.htm#i2232|Margaret Loveyne|b. c 1372\nd. 18 Apr 1408|p75.htm#i2233|Sir John Knyvet|b. c 1380\nd. 9 Nov 1445|p56.htm#i1673|Elizabeth Clifton|b. c 1392\nd. b 8 Dec 1461|p56.htm#i1674| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | between 1436 and 1439 | Titchmarsh Parish, Coates, Northampton, England1,5,6 |

| Marriage | before 30 November 1476 | Principal=Sibyl Fowler6 |

| Marriage* | before 1484 | Conflict=Sibyl Fowler7,8,9 |

| Burial | 1496 | Shirburne, Oxfordshire, England7,6 |

| Death* | 28 August 1496 | 1,7 |

| Probate* | 19 October 1496 | 7,6 |

| Feudal* | Coates (in Titchmarsh), Northamptonshire; Standbridge and Tilsworth, Bedfordshire; Petsoe (in Emberton), Buckinghamshire; North Reston, Lincolnshire; Barton St. John, Oxfordshire; Swaffham Prior, Cambridgeshire.6 | |

| Name Variation | Richard Chamberlain Esq.6 | |

| (Witness) Probate | 1470 | Principal=William Chamberlayne6 |

| Will* | 18 August 1496 | 7 |

Family | Sibyl Fowler b. c 1448, d. 1525 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 10 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 238-13.

- [S192] F. N. Craig, "Chamberlains in the Marbury Ancestry", p.319.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 53-10.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 53-11.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 16.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Chamberlain 12.

- [S195] Ronny Bodine, Chamberlain of Buckinghamshire and Northhamptonshire in "Chamberlain," listserve message 26 Mar 1999.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 53-12.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 5.

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 18.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-37.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 42.

- [S192] F. N. Craig, "Chamberlains in the Marbury Ancestry", p.318.

Sibyl Fowler

F, #1596, b. circa 1448, d. 1525

| Father* | Richard Fowler1,2 | |

| Mother* | Joan Danvers d. 1505 | |

Sibyl Fowler|b. c 1448\nd. 1525|p54.htm#i1596|Richard Fowler||p54.htm#i1597|Joan Danvers|d. 1505|p56.htm#i1670|||||||John Danvers||p470.htm#i14086|||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | circa 1448 | Of Rycott, Great Haseley, Oxfordshire, England |

| Birth | circa 1456 | |

| Marriage | before 30 November 1476 | Principal=Richard Chamberlayne2 |

| Marriage* | before 1484 | Conflict=Richard Chamberlayne3,4,5 |

| Death* | 1525 | 4 |

| Burial* | Shirburn, Oxfordshire, England2 | |

| Married Name | Chamberlayne6 |

Family | Richard Chamberlayne b. bt 1436 - 1439, d. 28 Aug 1496 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 6 Oct 2004 |

Citations

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 18.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Chamberlain 12.

- [S195] Ronny Bodine, Chamberlain of Buckinghamshire and Northhamptonshire in "Chamberlain," listserve message 26 Mar 1999.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 53-12.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 5.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-37.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 16.

Richard Fowler

M, #1597

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | Principal=Joan Danvers1 | |

| Occupation* | Chancellor of the Exchequer to King Edward IV2,3,4,5 | |

| Residence* | Sherbourne, Oxfordshire, England6,3,4 | |

| Title* | Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster6,5 |

Family | Joan Danvers d. 1505 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 6 Oct 2004 |

Citations

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 18.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-37.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 5.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 16.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Chamberlain 12.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 53-12.

Elizabeth Greene

F, #1598, b. circa 1416

|

| Father* | Sir Thomas Greene Knt.1,2,3 b. 10 Feb 1400, d. 18 Jan 1461/62 | |

| Mother* | Philippa de Ferrers1,2 | |

Elizabeth Greene|b. c 1416|p54.htm#i1598|Sir Thomas Greene Knt.|b. 10 Feb 1400\nd. 18 Jan 1461/62|p54.htm#i1602|Philippa de Ferrers||p54.htm#i1603|Sir Thomas Greene Knt.|b. bt 1369 - 1370\nd. 14 Dec 1417|p8.htm#i233|Mary Talbot|d. 13 Apr 1434|p54.htm#i1604|Sir Robert de Ferrers|b. 31 Oct 1357 or 31 Oct 1359\nd. 12 Mar 1413 or 13 Mar 1413|p71.htm#i2114|Margaret le Despencer|d. 3 Nov 1415|p58.htm#i1731| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | circa 1416 | Green's Norton, Northhamptonshire, England |

| Marriage* | before 1433 | Principal=William Raleigh Esq.4,5,6,7,8,9 |

| Married Name | Raleigh |

Family | William Raleigh Esq. b. s 1420, d. 14 Oct 1460 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 13 Mar 2008 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-35.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-10.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Greene 13.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-36.

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 15.

- [S191] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, "Royal Ancestry of Anne Marbury", p. 180.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-11.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 7.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 14.

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 16.

William Raleigh Esq.1

M, #1599, b. say 1420, d. 14 October 1460

| Father* | John Ralegh b. c 1382; son and heir2,3,4 | |

| Mother* | Idony Cotesford2,3,4 | |

William Raleigh Esq.|b. s 1420\nd. 14 Oct 1460|p54.htm#i1599|John Ralegh|b. c 1382|p54.htm#i1600|Idony Cotesford||p54.htm#i1601|Sir Thomas de Ralegh Knt.|b. c 1330\nd. 6 Nov 1396|p73.htm#i2177|Agnes Swinford||p73.htm#i2179|Sir Thomas Cotesford Knt.||p73.htm#i2185|||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | say 1420 | 3 |

| Marriage* | before 1433 | Principal=Elizabeth Greene5,6,7,8,3,4 |

| Death* | 14 October 1460 | 2,1,8,4 |

| Name Variation | Ralegh9 | |

| Residence* | Farnborough, Warwickshire, England3 |

Family | Elizabeth Greene b. c 1416 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 7 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 37.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-35.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 7.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 14.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-36.

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 15.

- [S191] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, "Royal Ancestry of Anne Marbury", p. 180.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-11.

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 14.

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 16.

John Ralegh1

M, #1600, b. circa 1382

| Father* | Sir Thomas de Ralegh Knt.1 b. c 1330, d. 6 Nov 1396 | |

| Mother* | Agnes Swinford2 | |

John Ralegh|b. c 1382|p54.htm#i1600|Sir Thomas de Ralegh Knt.|b. c 1330\nd. 6 Nov 1396|p73.htm#i2177|Agnes Swinford||p73.htm#i2179|John de Ralegh|b. b 1314\nd. b 29 Sep 1348|p73.htm#i2168|Rose Helion||p73.htm#i2170|Sir William Swinford Knt.||p73.htm#i2181|||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | circa 1382 | 3 |

| Marriage* | before 1397 | Principal=Idony Cotesford4,5,6 |

| Name Variation | Raleigh | |

| Residence* | Thornborow, Warwickshire, England5 |

Family | Idony Cotesford | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 7 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 13.

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 12.

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 14.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-35.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 7.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Cheseldine 14.

Idony Cotesford

F, #1601

| Father* | Sir Thomas Cotesford Knt.; daughter and heir1,2,3 | |

Idony Cotesford||p54.htm#i1601|Sir Thomas Cotesford Knt.||p73.htm#i2185||||Roger Cotesford||p449.htm#i13446|||||||||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | before 1397 | Principal=John Ralegh4,2,3 |

| Name Variation | Idoine5 | |

| Married Name | before 1397 | Ralegh4 |

Family | John Ralegh b. c 1382 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 7 Sep 2005 |

Sir Thomas Greene Knt.

M, #1602, b. 10 February 1400, d. 18 January 1461/62

|

| Father* | Sir Thomas Greene Knt.1,2,3,4 b. bt 1369 - 1370, d. 14 Dec 1417 | |

| Mother* | Mary Talbot1,5,2,3,4 d. 13 Apr 1434 | |

Sir Thomas Greene Knt.|b. 10 Feb 1400\nd. 18 Jan 1461/62|p54.htm#i1602|Sir Thomas Greene Knt.|b. bt 1369 - 1370\nd. 14 Dec 1417|p8.htm#i233|Mary Talbot|d. 13 Apr 1434|p54.htm#i1604|Sir Thomas Greene Knt.||p63.htm#i1887|Maud Mablethorp||p63.htm#i1888|Sir Richard Talbot|b. c 1361\nd. bt 8 Sep 1396 - 9 Sep 1396|p54.htm#i1605|Ankaret le Strange|b. 1361\nd. 1 Jun 1413|p69.htm#i2061| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Of | Green's Norton and Boughton, Northamptonshire6 | |

| Birth* | 10 February 1400 | Greene's Norton, Northamptonshire, England1,7,8 |

| Marriage* | before 16 December 1421 | Bride=Philippa de Ferrers1,7,8,4,9 |

| Marriage* | before 7 December 1434 | Private chapel in the house of Richard Knyghtley, Fawesley, Northamptonshire, England, This marriage was clandestine, 1st=Marine Bellars8,4 |

| Death* | 18 January 1461/62 | 1,10,11,7,8,4 |

| Burial* | Greene's Norton, Northamptonshire, England5,8,4 | |

| Note | The source of the children's names was the 1585 King of Arms Greene pedigree. Contemporary records have been found only for Thomas and Isabel., Principal=Philippa de Ferrers12 | |

| Occupation* | 4 November 1454 | Northamptonshire, England, Sheriff of Northamptonshire1,5 |

Family 1 | Marine Bellars b. c 1415, d. 10 Sep 1489 | |

| Children |

| |

Family 2 | Philippa de Ferrers | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 7 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-34.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-9.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Greene 9.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Greene 13.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 36.

- [S374] Douglas Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry, Greene 10.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-10.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Greene 8.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 105.

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 15.

- [S191] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, "Royal Ancestry of Anne Marbury", p. 181.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-35.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Hardwick 14.

Philippa de Ferrers1

F, #1603

| Father* | Sir Robert de Ferrers2,3 b. 31 Oct 1357 or 31 Oct 1359, d. 12 Mar 1413 or 13 Mar 1413 | |

| Mother* | Margaret le Despencer2,3 d. 3 Nov 1415 | |

Philippa de Ferrers||p54.htm#i1603|Sir Robert de Ferrers|b. 31 Oct 1357 or 31 Oct 1359\nd. 12 Mar 1413 or 13 Mar 1413|p71.htm#i2114|Margaret le Despencer|d. 3 Nov 1415|p58.htm#i1731|Sir John de Ferrers|b. 10 Aug 1331\nd. 3 Apr 1367|p71.htm#i2110|Elizabeth de Stafford|b. c 1337\nd. 7 Aug 1375|p71.htm#i2111|Sir Edward le Despenser K.G., M.P.|b. 24 Mar 1335/36\nd. 11 Nov 1375|p89.htm#i2646|Elizabeth de Burghersh|b. 1342\nd. c 26 Jul 1409|p89.htm#i2647| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | before 16 December 1421 | 1st=Sir Thomas Greene Knt.4,5,6,7,8 |

| Burial* | Greene's Norton, Northamptonshire, England8 | |

| Note | The source of the children's names was the 1585 King of Arms Greene pedigree. Contemporary records have been found only for Thomas and Isabel., Principal=Sir Thomas Greene Knt.9 | |

| Name Variation | Philippe Ferrers7 | |

| Living* | 1427 | 7 |

Family | Sir Thomas Greene Knt. b. 10 Feb 1400, d. 18 Jan 1461/62 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 20 Feb 2005 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 37.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 115-8.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Ferrers 11.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-34.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-10.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Greene 8.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Greene 13.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 105.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-35.

- [S190] F. N. Craig, "Ralegh of Farnborough", p. 15.

Mary Talbot

F, #1604, d. 13 April 1434

| Father* | Sir Richard Talbot1,2,3 b. c 1361, d. bt 8 Sep 1396 - 9 Sep 1396 | |

| Mother* | Ankaret le Strange1,2 b. 1361, d. 1 Jun 1413 | |

Mary Talbot|d. 13 Apr 1434|p54.htm#i1604|Sir Richard Talbot|b. c 1361\nd. bt 8 Sep 1396 - 9 Sep 1396|p54.htm#i1605|Ankaret le Strange|b. 1361\nd. 1 Jun 1413|p69.htm#i2061|Sir Gilbert Talbot|b. c 1332\nd. 24 Apr 1387|p54.htm#i1606|Pernel Butler|d. 1368|p54.htm#i1607|Sir John le Strange|b. 19 Apr 1332\nd. 12 May 1361|p69.htm#i2060|Mary FitzAlan|d. 1361|p91.htm#i2716| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | before 1383 | Groom=Sir Thomas Greene Knt.1,4,5,6 |

| Marriage | before 23 October 1398 | Conflict=Sir Thomas Greene Knt.6 |

| Marriage* | before 14 June 1420 | without license, Groom=John Notyngham5,7 |

| Burial* | Greene's Norton, Northamptonshire, England8,7 | |

| Death* | 13 April 1434 | 1,4,5,7 |

Family | Sir Thomas Greene Knt. b. bt 1369 - 1370, d. 14 Dec 1417 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 7 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-33.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 8.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 11.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-9.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Greene 9.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Greene 13.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Greene 12.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 36.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-34.

Sir Richard Talbot1

M, #1605, b. circa 1361, d. between 8 September 1396 and 9 September 1396

|

| Father* | Sir Gilbert Talbot2,3,4,5,6 b. c 1332, d. 24 Apr 1387 | |

| Mother* | Pernel Butler7,4,5,6 d. 1368 | |

Sir Richard Talbot|b. c 1361\nd. bt 8 Sep 1396 - 9 Sep 1396|p54.htm#i1605|Sir Gilbert Talbot|b. c 1332\nd. 24 Apr 1387|p54.htm#i1606|Pernel Butler|d. 1368|p54.htm#i1607|Sir Richard Talbot M.P.|b. c 1305\nd. 23 Oct 1356|p91.htm#i2718|Elizabeth Comyn|b. 1 Nov 1299\nd. 20 Nov 1372|p91.htm#i2719|Sir James Butler K.B.|b. 1305\nd. 6 Jan 1337/38|p54.htm#i1609|Eleanor de Bohun|d. 7 Oct 1363|p54.htm#i1608| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Of | Eccleswall (in Linton), Wormelow, Herefordshire, Ley (in Westbury upon Severn), Lydney Shrewsbury, Moreton Valence, and Painswick, Gloucestershire.8 | |

| Birth* | circa 1361 | 7,9,10,11,1,5 |

| Marriage* | before 23 August 1383 | 1st=Ankaret le Strange12,13,10,11,1,5 |

| Death* | between 8 September 1396 and 9 September 1396 | 7,12,10,11,1,5 |

| Knighted* | 16 July 1377 | by Richard II at his coronation, Witness=Richard II Plantagenet5 |

| Event-Misc | January 1381 | Ireland, was in Ireland with Edmund, Earl of March5 |

| Event-Misc* | between 3 March 1384 and 17 December 1387 | summoned to Parliament in consequence of his marriage to the heiress of Strange of Blackmere.11,1,5 |

| Event-Misc | 13 June 1385 | Newcastle-on-Tyne, Northumbria, England, summoned to be present 14 Jul for service against the Scots5 |

| Event-Misc | 18 June 1387 | seised of his father's lands5 |

| Event-Misc | between 1 December 1387 and 13 November 1393 | was summoned to Parliament by writ directed Ricard Talbot de Godriche Castell.5 |

| Event-Misc | 31 December 1389 | was (upon the death of the 3rd Earl of Pembroke) awarded the Honor of Wexford in Ireland, as coheir through Elizabeth Comyn, his grandmother.5 |

| Event-Misc | 1 March 1392 | Shropshire, England, was commissioner of array for Shropshire5 |

| Event-Misc | February 1395 | Ireland, was in Ireland in the King's service.5 |

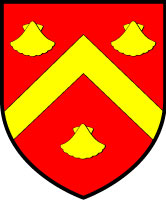

| Arms* | Gules a lion and a border engrailed or1 |

Family | Ankaret le Strange b. 1361, d. 1 Jun 1413 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 7 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 11.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 39.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 141-6.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 9.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, XII - 616.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 10.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-32.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 8.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p.36.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 141-7.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 8.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 36.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 34-8.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-33.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 246.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, XII - 617.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 7-31.

Sir Gilbert Talbot1,2

M, #1606, b. circa 1332, d. 24 April 1387

| Father* | Sir Richard Talbot M.P.3,2 b. c 1305, d. 23 Oct 1356 | |

| Mother* | Elizabeth Comyn3,4,2 b. 1 Nov 1299, d. 20 Nov 1372 | |

Sir Gilbert Talbot|b. c 1332\nd. 24 Apr 1387|p54.htm#i1606|Sir Richard Talbot M.P.|b. c 1305\nd. 23 Oct 1356|p91.htm#i2718|Elizabeth Comyn|b. 1 Nov 1299\nd. 20 Nov 1372|p91.htm#i2719|Sir Gilbert Talbot|b. 18 Oct 1276\nd. 24 Feb 1346|p365.htm#i10933|Anne le Boteler||p365.htm#i10934|John Comyn|d. 10 Feb 1306|p91.htm#i2720|Joan de Valence||p91.htm#i2721| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Of | Eccleswall (in Linton), Wormelow, Herefordshire, Ley (in Westbury upon Severn), Lydney Shrewsbury, Moreton Valence, and Painswick, Gloucestershire.5 | |

| Birth* | circa 1332 | 6,1,4,7,8 |

| Marriage* | before 8 September 1352 | Bride=Pernel Butler9,4,7,2,10 |

| Marriage* | before 16 November 1379 | Pardoned on that date for marrying without license., 2nd=Joan de Stafford7,10,2 |

| Death* | 24 April 1387 | Roales, Spain, of pestilence9,1,4,7,10,2 |

| Event-Misc | 1 February 1357 | Gascony, France, was in the King's service in Gascony with the Prince of Wales.8 |

| Event-Misc* | 14 August 1362 | Member of Parliament6,4,7 |

| Event-Misc | between 14 August 1362 and 8 August 1386 | was summoned to Parliament10,2 |

| Event-Misc | 16 July 1377 | did homage to Richard II at his coronation10 |

| Event-Misc | 6 June 1380 | pardoned for failing to appear to answer John Sewal, citizen and mercer of London, touching a debt of £300.10 |

| Event-Misc | between 1381 and 1382 | Portugal, accompanied Edmund of York on his expedition to Portugal7 |

| Event-Misc | between 1381 and 1382 | Higuera la Real, Badajoz, Portugal, accompanied Edmund of Langley, Earl of Cambridge on his expedition to Portual, taking part in the capture of Higuera la Real.10 |

| Event-Misc | 7 July 1381 | Hereford, England, was commissioner for hereford at the time of the Peasants' Revolt with duties to array the lieges against the insurgents10 |

| Event-Misc | 13 June 1385 | Newcastle-on-Tyne, Northumbria, England, summoned to be present 14 Jul for service against the Scots10 |

| Event-Misc | July 1386 | Spain, was with John of Gaunt on his expedition to Spain. Present at the capture of Vigo and the affair at Noya, and accompanied the Duchess Constance to visit the King of Portugal at Oporto.7,10 |

| Title* | 3rd Lord Talbot2 |

Family | Pernel Butler d. 1368 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 7 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 39.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 10.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 95-31.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 141-6.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 7.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 13-31.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 9.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, XII - 614.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-31.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, XII - 615.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, XII - 616.

Pernel Butler1,2

F, #1607, d. 1368

| Father* | Sir James Butler K.B.3,4,5 b. 1305, d. 6 Jan 1337/38 | |

| Mother* | Eleanor de Bohun6,4,5 d. 7 Oct 1363 | |

Pernel Butler|d. 1368|p54.htm#i1607|Sir James Butler K.B.|b. 1305\nd. 6 Jan 1337/38|p54.htm#i1609|Eleanor de Bohun|d. 7 Oct 1363|p54.htm#i1608|Sir Edmund Butler Knt.|b. c 1282\nd. 13 Sep 1321|p70.htm#i2081|Joan FitzJohn||p54.htm#i1610|Sir Humphrey V. de Bohun|b. 1276\nd. 16 Mar 1322|p54.htm#i1612|Elizabeth Plantagenet|b. 7 Aug 1282\nd. 5 May 1316|p54.htm#i1613| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | before 8 September 1352 | 1st=Sir Gilbert Talbot7,8,1,2,9 |

| Death* | 1368 | 6,1,9,2 |

| Name Variation | Petronilla le Boteler | |

| Event-Misc | 1363 | She was a legatee in the will of her mother10 |

| Living* | 28 May 1365 | 6,1,9,2 |

Family | Sir Gilbert Talbot b. c 1332, d. 24 Apr 1387 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 7 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 9.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 10.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 39.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 26-7.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Butler 10.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 13-31.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-31.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 141-6.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, XII - 615.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 7.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 14-32.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, XII - 616.

Eleanor de Bohun

F, #1608, d. 7 October 1363

|

| Father* | Sir Humphrey VIII de Bohun1,2,3 b. 1276, d. 16 Mar 1322 | |

| Mother* | Elizabeth Plantagenet2,3 b. 7 Aug 1282, d. 5 May 1316 | |

Eleanor de Bohun|d. 7 Oct 1363|p54.htm#i1608|Sir Humphrey VIII de Bohun|b. 1276\nd. 16 Mar 1322|p54.htm#i1612|Elizabeth Plantagenet|b. 7 Aug 1282\nd. 5 May 1316|p54.htm#i1613|Sir Humphrey V. de Bohun|b. Sep 1248\nd. 31 Dec 1298|p70.htm#i2084|Maud de Fiennes|b. c 1254\nd. b 31 Dec 1298|p70.htm#i2085|Edward I. "Longshanks" Plantagenet King of England|b. 17 or 18 Jun 1239\nd. 7 Jul 1307|p54.htm#i1614|Eleanor of Castile|b. 1240\nd. 28 Nov 1290|p54.htm#i1615| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | 1327 | Groom=Sir James Butler K.B.1,2,4,5,6 |

| Marriage* | before 20 April 1344 | Chapel of the Manor of Vachery, Surrey, England, Groom=Sir Thomas Dagworth Knt. M.P.4,7 |

| Death* | 7 October 1363 | 8,2,4 |

| Married Name | Butler |

Family 1 | Sir Thomas Dagworth Knt. M.P. d. bt Jul 1350 - Aug 1350 | |

| Child |

| |

Family 2 | Sir James Butler K.B. b. 1305, d. 6 Jan 1337/38 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 6 Feb 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 13-30.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 24-6.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Bohun 8.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Butler 10.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Butler 9.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, X - 117.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 32.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 13-12.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, FitzWalter 8.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 13-31.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 26-7.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 7-31.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Butler 9.

Sir James Butler K.B.1,2

M, #1609, b. 1305, d. 6 January 1337/38

|

| Father* | Sir Edmund Butler Knt.1,5,3,2,4 b. c 1282, d. 13 Sep 1321 | |

| Mother* | Joan FitzJohn3,2,4 | |

Sir James Butler K.B.|b. 1305\nd. 6 Jan 1337/38|p54.htm#i1609|Sir Edmund Butler Knt.|b. c 1282\nd. 13 Sep 1321|p70.htm#i2081|Joan FitzJohn||p54.htm#i1610|Theobald Butler|b. 1242\nd. 26 Sep 1285|p70.htm#i2080|Joan FitzJohn|d. bt 25 Feb 1303 - 26 May 1303|p70.htm#i2083|Sir John FitzThomas FitzGerald Knt.|b. bt 1260 - 1270\nd. 12 Sep 1316|p70.htm#i2082|Blanche Roche|d. a Feb 1329/30|p92.htm#i2737| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Of | Knocktopher, co. Kilkenney, Turvy, co. Dublin, Nenagh and Thurles, co. Tipperary, Aylesbury, Great Linford, and Totherfield Peppard, Buckinghamire, Sopley, Hampshire, La Vacherie (in Cranley) and Shere, Surrey, Weeton, Lancashire6 | |

| Birth* | 1305 | 7,5,8 |

| Marriage* | 1327 | 1st=Eleanor de Bohun9,5,3,2,8 |

| Death* | 6 January 1337/38 | 1,10,5,3,2,11 |

| Burial* | Gowran, Tipperary, Ireland3,2,12 | |

| DNB* | Butler, James, first earl of Ormond (c.1305-1338), magnate, was the eldest surviving son of Edmund Butler (d. 1321) and his wife, Joan, daughter of John fitz Thomas Fitzgerald (d. 1316), who was created earl of Kildare in 1316. He married in 1328 Eleanor de Bohun (d. 1363), daughter of Humphrey (VII) de Bohun, earl of Hereford (d. 1322), and granddaughter of Edward I, an alliance that augmented the Butlers' English properties. James's name may reflect his father's devotion to Santiago de Compostela, for in 1320 Edmund, his wife, and son were released from a vow to visit the shrine of St James. James, who was in Ireland when Edmund died at London, was summoned to England and by February 1323 was a yeoman (valettus) in Edward II's household. In 1325 the king granted him his lands and marriage before he was of full age and the court speeded his return to Ireland where his lordships in Munster and Leinster were threatened by Irish raids. The first steps of his career were thus taken during the ascendancy of the Despensers, who established links with several leading Anglo-Irish families. Their fall in 1326 left Ireland unstable and the new rulers of England uncertain of the allegiance of the magnates. James Butler was drawn into regional feuds and was among those who received reprimands from England between December 1326 and June 1328. At that point, however, his father's close relations with Roger Mortimer (Edmund had been justiciar of Ireland during Mortimer's lieutenancy in 1317–18 and they had negotiated a marriage alliance in 1321), and the search for stability in Ireland on the part of the Mortimer regime, worked to his advantage. At the Salisbury parliament in October 1328, where Mortimer became earl of March, James Butler was created earl of Ormond and given a life-grant of the liberty of Tipperary, which in the event his descendants were to hold until 1716. At the same time his marriage to Edward III's cousin drew him towards the apex of aristocratic society. The new earl's career was often dominated by campaigns against the native Irish who threatened his lands in Tipperary and south Leinster. In 1329, for instance, he burnt the territory of the Ó Nualláin family in Carlow in revenge for the capture of his brother; and in 1336 he made a compact with the Ó Ceinnéidigh family of north Tipperary, in which they agreed to provide rent and military service, while Ormond accepted arrangements for mutual compensation between the Irish and the English settlers. His role in Irish marcher society was compatible with a career on a wider stage and could indeed be used to advertise his indispensability. The fall of Mortimer in 1330, and the resumption of grants made under his influence, rendered Ormond's gains of 1328 vulnerable. Faced by the strong methods of the justiciar, Anthony Lucy, the earl crossed to England and spent part of 1332 at his town of Aylesbury, subjecting Edward III to petitions in which he stressed his military services in Ireland, his relationship to the royal house, and the antiquity of his family and its possession of the butlerage of Ireland since the time of King John. As well as protecting his threatened endowments, he obtained financial rewards. His relations with Edward were further advanced when he led a retinue of 318 men from Ireland to the Scottish campaign of 1335. Ormond died on 16 or 18 February 1338 at Gowran, Kilkenny, before his intention to endow a Franciscan house at Carrick-on-Suir in Tipperary was carried through. The Kilkenny chronicler, Friar John Clyn, an admirer of the Butler family, lamented his death: he was ‘a generous and amiable man, elegant and courteous; in the bloom of youth the flower withered’ (Annals of Ireland, ed. Butler, 28). Ormond was buried with his father at Gowran. Inquisitions taken at his death show that, besides his Irish lordships, he had property in ten English counties, all held jointly with his wife, who by 1344 had married Sir Thomas Dagworth. The earl was succeeded by his surviving son, James Butler, who was granted his lands in 1347 while still under age. Robin Frame Sources Chancery records · PRO · E. Curtis, ed., Calendar of Ormond deeds, IMC, 1: 1172–1350 (1932) · C. A. Empey, ‘The Butler lordship’, Journal of the Butler Society, 1 (1970–71), 174–87 · R. Frame, English lordship in Ireland, 1318–1361 (1982) · The annals of Ireland by Friar John Clyn and Thady Dowling: together with the annals of Ross, ed. R. Butler, Irish Archaeological Society (1849) · J. T. Gilbert, ed., Chartularies of St Mary's Abbey, Dublin: with the register of its house at Dunbrody and annals of Ireland, 2, Rolls Series, 80 (1884) · CEPR letters, 2.196; 3.263–4 · G. O. Sayles, ed., Documents on the affairs of Ireland before the king's council, IMC (1979) · RotP · CIPM, 8, no. 184 Archives NL Ire., deeds © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Robin Frame, ‘Butler, James, first earl of Ormond (c.1305-1338)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/50021, accessed 23 Sept 2005] James Butler (c.1305-1338): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5002113 | |

| Name Variation | le Boteler6 | |

| Name Variation | le Botiller14 | |

| Event-Misc | 1317 | Dublin, Ireland, held hostage for his father in Dublin Castle3,2 |

| Event-Misc | 1321 | He was a legatee in his father's will6 |

| Event-Misc | 2 December 1325 | He was given license to marry whom he would, and although under age, Edward II took his homage.12 |

| Protection* | 1326 | to Ireland6 |

| Knighted* | 1326 | as a Knight of the Bath8 |

| Event-Misc* | 2 November 1328 | Created Earl of Ormond7,3,2,4 |

| Title* | Chief Butler of Ireland, Lieutenant of Ireland3,2 |

Family | Eleanor de Bohun d. 7 Oct 1363 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 23 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 39.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Butler 9.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Butler 10.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, II - 450.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 24-6.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Butler 6.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 7-30.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, X - 117.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 13-30.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 73-32.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 48.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 49.

- [S376] Unknown editor, unknown short title.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, FitzWalter 8.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 26-7.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, X - 119.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 24-7.

Joan FitzJohn1

F, #1610

| Father* | Sir John FitzThomas FitzGerald Knt.1,2,3,4,5 b. bt 1260 - 1270, d. 12 Sep 1316 | |

| Mother* | Blanche Roche6,5 d. a Feb 1329/30 | |

Joan FitzJohn||p54.htm#i1610|Sir John FitzThomas FitzGerald Knt.|b. bt 1260 - 1270\nd. 12 Sep 1316|p70.htm#i2082|Blanche Roche|d. a Feb 1329/30|p92.htm#i2737|Thomas FitzMaurice FitzGerald|d. 1271|p365.htm#i10930|Rohesia de St. Michael||p493.htm#i14774|John Roche of Fermoy||p92.htm#i2738|||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | 1302 | Principal=Sir Edmund Butler Knt.1,6,3,4,5 |

| Death | before 2 May 1320 | 7 |

Family | Sir Edmund Butler Knt. b. c 1282, d. 13 Sep 1321 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 6 Feb 2005 |

Citations

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 39.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 178A-7.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Butler 10.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Butler 9.

- [S287] G. E. C[okayne], CP, II - 450.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 73-31.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 48.

Sir James Butler Earl of Ormond1

M, #1611, b. 4 October 1331, d. circa November 1382

|

| Father* | Sir James Butler K.B.2 b. 1305, d. 6 Jan 1337/38 | |

| Mother* | Eleanor de Bohun3,4 d. 7 Oct 1363 | |

Sir James Butler Earl of Ormond|b. 4 Oct 1331\nd. c Nov 1382|p54.htm#i1611|Sir James Butler K.B.|b. 1305\nd. 6 Jan 1337/38|p54.htm#i1609|Eleanor de Bohun|d. 7 Oct 1363|p54.htm#i1608|Sir Edmund Butler Knt.|b. c 1282\nd. 13 Sep 1321|p70.htm#i2081|Joan FitzJohn||p54.htm#i1610|Sir Humphrey V. de Bohun|b. 1276\nd. 16 Mar 1322|p54.htm#i1612|Elizabeth Plantagenet|b. 7 Aug 1282\nd. 5 May 1316|p54.htm#i1613| | ||

| Birth* | 4 October 1331 | Kilkenny, Ireland3,2,4 |

| Marriage* | 13 May 1346 | Principal=Ann Darcy3,2,4 |

| Death* | circa November 1382 | 3,2,4 |

| Last Edited | 2 Aug 2004 |

Sir Humphrey VIII de Bohun1

Sir Humphrey VIII de Bohun1

M, #1612, b. 1276, d. 16 March 1322

| Father* | Sir Humphrey VII de Bohun2,3,4,5 b. Sep 1248, d. 31 Dec 1298 | |

| Mother* | Maud de Fiennes2,3,4,5,6 b. c 1254, d. b 31 Dec 1298 | |

Sir Humphrey VIII de Bohun|b. 1276\nd. 16 Mar 1322|p54.htm#i1612|Sir Humphrey VII de Bohun|b. Sep 1248\nd. 31 Dec 1298|p70.htm#i2084|Maud de Fiennes|b. c 1254\nd. b 31 Dec 1298|p70.htm#i2085|Sir Humphrey V. de Bohun|d. 27 Oct 1265|p70.htm#i2087|Eleanor de Braiose|d. b 1264|p92.htm#i2743|Sir Enguerrand de Fiennes|d. 1265|p70.htm#i2086|Isabel de Condé|b. c 1210|p231.htm#i6907| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | 1276 | 7,5 |

| Marriage* | 14 November 1302 | Westminster, Middlesex, England, by papal dispensation, Principal=Elizabeth Plantagenet7,2,8,9,5,1 |

| Death* | 16 March 1322 | Battle of Boroughbridge, Boroughbridge, Yorkshire, England, slain at Boroughbridge fighting against the King.7,2,10,8,5,11 |

| Burial* | Church of the Friars Preachers, York, Yorkshire, England5 | |

| Feudal* | Kington, Herefordshire, Pleshy, Debden, Fobbing, Saffron Walden, Shenfield, Essex, Kimbolton, Huntingdonshire, Enfield, Middlesex, Brecknock and Hay, Breconshire, Caldicott, Monmouthshire12 | |

| Occupation | Lord High Constable of England10 | |

| Event-Misc | 22 July 1298 | Battle of Falkirk, Falkirk, Scotland, See Battle of Falkirk. 1 |

| (English) Battle-Falkirk | 22 July 1298 | Principal=Edward I "Longshanks" Plantagenet King of England13,14,15 |

| Event-Misc* | 1 July 1300 | Carlaverock Castle, Scotland, present at the seige of Carlaverock. "A rich and elegant young man." A poem commemorates the battle.5,1,11 |

| Event-Misc | 1301 | He signed the barons' letter to Pope Boniface as Com' Hereford et Essex & Constab' Angl'.12 |

| Event-Misc* | 1303 | Enfield, Essex, They were granted market and fair, Principal=Elizabeth Plantagenet12 |

| Event-Misc | 1306 | He was granted the castle of Lochmaben and lordship of Annandale12 |

| Event-Misc | 18 October 1306 | He had his lands confiscated for desertion in Scotland11 |

| Event-Misc | 28 February 1308 | He bore the sceptre at the Coronation of Edward II11 |

| Event-Misc | 1310 | He was sworn as one of the Lords Ordainers to reform the government and the King's household.12 |

| Event-Misc | 1312 | Scarborough, He was one of the Barons who besieged and captured Piers de Gaveston, favorite of Edward II12 |

| Event-Misc | October 1313 | He was pardoned re Gaveston12 |

| Note* | 24 June 1314 | Battle of Bannockburn, fought at Bannockburn . He and the Earl of Gloucester wer in dispute as to whom would take precedence in the battle line; when the Earl of Gloucester dashed forward, his horse fell and he was killed. After the English were defeatred, Hereford retreated to bothwell, where Gov. Sir Walter Gilbertson gave him up to the Scots, who later exchanged him for Elizabeth de Burgh, wife of Robert the Bruce and the Bishop of St. Andrews2,5,11,16 |

| Event-Misc | 11 February 1315/16 | He was captain of the forces against Llywelyn Bren ap Rhys in Glamorgan, Wales16 |

| Will* | 11 August 1318 | 5 |

| Event-Misc | 8 November 1318 | He was on a diplomatic mission to the Counts of Flanders, hainault, Holland, and Zealand16 |

| Event-Misc | between May 1321 and June 1321 | Humphrey ravaged the lands of Hugh le Despenser the Younger, Witness=Sir Hugh le Despenser16 |

| (Rebel) Battle-Boroughbridge | 16 March 1321/22 | Principal=Edward II Plantagenet, Principal=Sir Thomas of Lancaster17,18,16 |

| HTML* | History of the Bown Surname | |

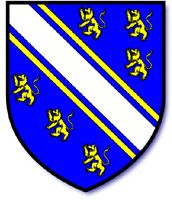

| Arms* | Azure with a bend of silver and cotises of gold between six golden lioncels1 | |

| Arms | Az. A bend arg., cottised or, bet. 6 lioncels or. A label gu. (Carlaverock).19 |

Family | Elizabeth Plantagenet b. 7 Aug 1282, d. 5 May 1316 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 14 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Bohun 8.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 39.

- [S232] Don Charles Stone, Ancient and Medieval Descents, 21-12.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 18-4.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Bohun 12.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Bohun 7.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 6-29.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 18-5.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 96-31.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 108.

- [S374] Douglas Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry, Bohun 5.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 5.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 125.

- [S347] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Certain Americans, p. 35.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 31.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 2, p. 114.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 5, p. 3.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 107.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 13-30.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 24-6.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 15-30.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Bohun 11.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 6-30.

Elizabeth Plantagenet

F, #1613, b. 7 August 1282, d. 5 May 1316

| Father* | Edward I "Longshanks" Plantagenet King of England1,2,3 b. 17 or 18 Jun 1239, d. 7 Jul 1307 | |

| Mother* | Eleanor of Castile1,4,3 b. 1240, d. 28 Nov 1290 | |

Elizabeth Plantagenet|b. 7 Aug 1282\nd. 5 May 1316|p54.htm#i1613|Edward I "Longshanks" Plantagenet King of England|b. 17 or 18 Jun 1239\nd. 7 Jul 1307|p54.htm#i1614|Eleanor of Castile|b. 1240\nd. 28 Nov 1290|p54.htm#i1615|Henry I. Plantagenet King of England|b. 1 Oct 1207\nd. 16 Nov 1272|p54.htm#i1618|Eleanor of Provence|b. 1217\nd. 24 Jun 1291|p54.htm#i1619|Fernando I. of Castile "the Saint"|b. bt 5 Aug 1201 - 19 Aug 1201\nd. 30 May 1252|p95.htm#i2832|Joan de Dammartin|b. c 1218\nd. 16 Mar 1279|p95.htm#i2833| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | 7 August 1282 | Rhudlan Castle, Caernavon, Wales1,2,5,6,3 |

| Marriage* | 7 January 1297 | Ipswich, England, Principal=Graf Johann von Holland6,3 |

| Marriage* | 14 November 1302 | Westminster, Middlesex, England, by papal dispensation, Principal=Sir Humphrey VIII de Bohun1,7,5,2,6,3 |

| Death* | 5 May 1316 | Quendon, Essex, England1,7,2,5,8 |

| Burial* | Walden Abbey, Essex, England2,6,8 | |

| Event-Misc* | 1303 | Enfield, Essex, They were granted market and fair, Principal=Sir Humphrey VIII de Bohun8 |

Family | Sir Humphrey VIII de Bohun b. 1276, d. 16 Mar 1322 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 14 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 6-29.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Bohun 8.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 14.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 18-5.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Bohun 12.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 39.

- [S374] Douglas Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry, Bohun 5.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 24-6.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 31.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 18-6.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Bohun 11.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 13-30.

Edward I "Longshanks" Plantagenet King of England1

Edward I "Longshanks" Plantagenet King of England1

M, #1614, b. 17 or 18 Jun 1239, d. 7 July 1307

| |

| |

| Father* | Henry III Plantagenet King of England b. 1 Oct 1207, d. 16 Nov 1272; son and heir2,3,4,5 | |

| Mother* | Eleanor of Provence b. 1217, d. 24 Jun 1291; son and heir6,3,7,5 | |

Edward I "Longshanks" Plantagenet King of England|b. 17 or 18 Jun 1239\nd. 7 Jul 1307|p54.htm#i1614|Henry III Plantagenet King of England|b. 1 Oct 1207\nd. 16 Nov 1272|p54.htm#i1618|Eleanor of Provence|b. 1217\nd. 24 Jun 1291|p54.htm#i1619|John Lackland|b. 27 Dec 1166\nd. 19 Oct 1216|p54.htm#i1620|Isabella of Angoulême|b. 1188\nd. 31 May 1246|p55.htm#i1621|Raymond V. Berenger|b. 1198\nd. 19 Aug 1245|p94.htm#i2797|Beatrice of Savoy|b. 1198\nd. Dec 1266|p94.htm#i2798| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | 17 or 18 Jun 1239 | Westminster, London, England, 17 or 18 Jun 12392,8,9 |

| Marriage* | 18 October 1254 | Monastery of Las Huelgas, Burgos, Spain, Bride=Eleanor of Castile2,10,8,4,9 |

| Marriage* | 8 September 1299 | Canterbury Cathedral, Canterbury, Kent, England, by dispensation dated 1 Jul 1298, they being related in the 2nd and 3rd degrees), Principal=Marguerite Of France2,10,8,4,9 |

| Death* | 7 July 1307 | Burgh-on-Sands, Cumberland, England, 7 or 8 Jul 13072,10,8,9 |

| Burial* | 28 October 1307 | Westminster Abbey, Westminster, England10 |

| Dickens* | 11 | |

| Hume* | 12 | |