Sir William de la Pole1

M, #1711, d. 1366

| Father* | William de la Pole1 d. c 1329 | |

| Mother* | Elena (?)1 | |

Sir William de la Pole|d. 1366|p58.htm#i1711|William de la Pole|d. c 1329|p497.htm#i14891|Elena (?)||p497.htm#i14892||||||||||||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | Principal=Catherine Norwich1 | |

| Death* | 1366 | 2 |

| Occupation | Baron of the Exchequer2 | |

| Occupation* | 1332 | Hull, England, Mayor of Hull2 |

| Event-Misc* | 1339 | The Poles were wealthy merchants of Hull. "During the war with France, the king was reduced to great straits through the want of money. At this critical period he appealed to William De la Pole, who advanced him the immense sum of £76,180. Constant to the last in his friendship and regard for his sovereign, Sir William, when impotent and of great age, gave Edward a full release of all debts the monarch owed him." -Bulmer's Gazetteer (1892)3 |

Family | Catherine Norwich | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 17 Apr 2005 |

Citations

- [S285] Leo van de Pas, 30 Jun 2004.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-33.

- [S345] History of Hull, online http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ERY/Hull/HullHistory/…

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Marmion 10.

Catherine de la Pole

F, #1712

| Father* | Sir William de la Pole1,2 d. 1366 | |

| Mother* | Catherine Norwich | |

Catherine de la Pole||p58.htm#i1712|Sir William de la Pole|d. 1366|p58.htm#i1711|Catherine Norwich||p497.htm#i14885|William de la Pole|d. c 1329|p497.htm#i14891|Elena (?)||p497.htm#i14892|Sir Walter de Norwich|d. 20 Feb 1329|p468.htm#i14030|||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | Principal=Constantine de Clifton1,2 | |

| Married Name | Clifton1 |

Family | Constantine de Clifton d. b 1373 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 17 Apr 2005 |

Elizabeth Cromwell

F, #1713, d. 24 September 1391

| Father* | Sir Ralph Cromwell1 d. 27 Aug 1398 | |

| Mother* | Maud Bernacke1 b. bt 1335 - 1338, d. 10 Apr 1419 | |

Elizabeth Cromwell|d. 24 Sep 1391|p58.htm#i1713|Sir Ralph Cromwell|d. 27 Aug 1398|p58.htm#i1715|Maud Bernacke|b. bt 1335 - 1338\nd. 10 Apr 1419|p58.htm#i1716|Ralph de Cromwell|d. b 28 Oct 1364|p59.htm#i1744|Anice de Bellers||p59.htm#i1745|Sir John Bernacke|b. bt 1305 - 1306\nd. 20 Mar 1346|p58.htm#i1717|Joan Marmion|d. 2 Oct 1361 or 13 Oct 1361|p58.htm#i1718| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | Groom=Sir John de Clifton1,2 | |

| Death* | 24 September 1391 | 2 |

| Death | between 1393 and 1394 | 1 |

| Married Name | Clifton1 |

Family | Sir John de Clifton b. c 1353, d. 10 Aug 1388 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 13 Oct 2004 |

Sir Ralph Cromwell1

M, #1715, d. 27 August 1398

| Father* | Ralph de Cromwell d. b 28 Oct 1364; son and heir2,3,1 | |

| Mother* | Anice de Bellers4,3,1 | |

Sir Ralph Cromwell|d. 27 Aug 1398|p58.htm#i1715|Ralph de Cromwell|d. b 28 Oct 1364|p59.htm#i1744|Anice de Bellers||p59.htm#i1745|Ralph de Cromwell|b. c 1292|p59.htm#i1747|Joan de la Mare|d. 9 Aug 1348|p85.htm#i2550|Roger de Bellers|d. 1326|p59.htm#i1746|||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | before 20 January 1360/61 | Principal=Maud Bernacke1 |

| Marriage | before 20 June 1366 | Conflict=Maud Bernacke5,6,7 |

| Death* | 27 August 1398 | 8,1 |

| Feudal* | Cromwell, Nottinghamshire, West Hallam, Derbyshire, and in right of his wife, Tattershall Castle, Lincolnshire, and Lutton, Northamptonshire.1 | |

| DNB* | Cromwell, Ralph, third Baron Cromwell (1393?-1456), administrator, came of a long-established midland family. Soldier and diplomat One of Cromwell's ancestors, a king's thegn named Alden, had held land at Cromwell in Nottinghamshire as part of his knight's fee at the time of the Domesday inquest (1086), while his grandfather, another Ralph (d. 1398), had been summoned to parliament as Lord Cromwell in 1375. The son of Ralph, second Baron Cromwell (d. 1416), and his wife, Joan, the third Lord Cromwell did not come into the barony of Tattershall, with which he is normally associated, until the death of his paternal grandmother, Maud Barnack, in 1419. As a youth he gained a place in the household of Henry IV's second son, Thomas, duke of Clarence (d. 1421), and the connection with Clarence soon led to the expanding of Cromwell's horizons. The civil war that broke out in France in 1410 between the dukes of Burgundy and Orléans led to English intervention. Cromwell was part of the army which under Clarence's command crossed to Normandy in August 1412 and campaigned into the duchy of Orléans. When, in November, arrangements were made by which the English were given a substantial payment to be on their way home, Clarence, with Cromwell, went into Gascony to wait out the winter, and returned to England early in April 1413. The French wars of Henry V's reign offered Cromwell an opportunity for further advancement, and he participated in the capture of Harfleur and fought at Agincourt in 1415. In the Normandy campaign of 1417 Cromwell was present at the capture of Caen. Notice must have been taken of Cromwell's talent for administration, for Clarence appointed Cromwell to be his lieutenant in command of the garrisons of Bec, Poissy, and Pontoise; then in 1421 Cromwell became captain of Harfleur. He must also have shown a talent for diplomacy, since he was one of the men appointed to negotiate the treaty of Troyes of 1420. Cromwell had become one of Henry V's most trusted diplomats and captains and, following the sudden death of the king in 1422, it is no surprise that Cromwell was given one of the four places for knights on the council established by parliament in 1422 for the governance of England during the minority of Henry VI. This parliament was the first to which Cromwell was summoned, and thereafter he concentrated on administration and finance. In this period he married Margaret (d. 1454), coheir with her sister of the valuable midland estates of John, Lord Deincourt (d. 1422). Furthermore, he established what would be a long political association with Henry Beaufort, bishop of Winchester (d. 1447), and Cromwell's political fortunes tended to wax and wane with those of Beaufort. Treasurer of England, 1433–1443 Cromwell was summoned to Rouen in 1431 during the trial of Jeanne d'Arc, and probably witnessed her death at the stake. He was also in France for Henry VI's coronation in Paris on 16 December 1431. Some time in the late 1420s or early 1430s Cromwell had become the king's chamberlain. But on 1 March 1432 he lost that office, as part of a move against Beaufort and his associates by the king's uncle Humphrey, duke of Gloucester. However, when the king's senior uncle, John, duke of Bedford, interrupted his labours as regent of Lancastrian France to attend to business in England, he secured Cromwell's promotion to be treasurer of England on 11 August 1433, replacing Gloucester's friend, John, Lord Scrope of Masham. As head of the exchequer Cromwell faced extreme fiscal problems. According to the estimate he prepared on taking office, the indebtedness of the crown amounted to £164,000, with an estimated level of annual expenditure of £56,000, and an anticipated annual income of only £38,000. The greatest single drain on crown resources was the French war, which dominated Cromwell's treasurership. In his decade as treasurer, Cromwell did not succeed in bringing stability to government finances, and the crown debt expanded to an alarming size. Cromwell's personal wealth, however, grew steadily during his treasurership, in part because he seized upon opportunities made available to him as one of the great officers of state to acquire lands, wardships, reversions, and other fruits of patronage and power. During his treasurership Cromwell was able to lend the crown over £4000, as well as to embark on impressive building projects. At his death, Cromwell left over £21,000 in goods and money alone, while his executors subsequently returned to their owners lands worth £5500 of which Cromwell had unjustly deprived them. That is not to say that Cromwell was not an energetic and conscientious treasurer, for by all indications he was, but his desire to hold down governmental spending was not shared by enough of the king's councillors. That Cromwell was treasurer of England longer than any man since William Edington (treasurer from 1344 to 1356) is suggestive of his mastery of the demands of his office as well as a tribute to his political abilities. It was changes in the political climate that led to Cromwell's resignation as treasurer on 6 July 1443, and his replacement the next day by Ralph Boteler, Lord Sudeley (d. 1473). In particular, this was the period which saw William de la Pole, earl of Suffolk (d. 1450), emerge as the most prominent of the king's councillors. Cromwell, unlike Sudeley, was not one of Suffolk's supporters, hence his replacement as treasurer. The reasons given for his resignation, ill health and the burdens of office, are belied by his continuing activity and vigour. In any case, Cromwell retained his place on the king's council, and continued to attend meetings on a regular basis. He remained as well one of the two chamberlains of the exchequer, an office he had obtained while treasurer, and arrangements Cromwell had set up for the repayment of loans he had made to the crown were allowed to stand. Political difficulties, 1443–1456 Cromwell thus ceased in 1443 to be one of the great officers of state, but was not utterly stripped of influence and position. Although there seems as yet to have been no rancour between Cromwell and Suffolk, Cromwell was nevertheless outside the most influential circle in government. The gradual withdrawal of Beaufort from government in the 1440s, and his death in 1447, did nothing to aid Cromwell's position. Cromwell had established ties with Richard, duke of York (d. 1460), becoming one of York's annuitants before 1441, but York was far from influential during Suffolk's ascendancy. Indeed, York was appointed lieutenant of Ireland in 1447, probably as a way of removing him more completely from the scene (though he did not take up the post until March 1448). A change in Cromwell's political life began abruptly with a physical assault upon his person, on 28 November 1449. While parliament was in session, and as Cromwell came from a council meeting in the Star Chamber at Westminster, he was set upon by a band of men with murderous intent led by William Tailboys (d. 1464). With the aid of his retainers Cromwell escaped the assault. Tailboys, a wealthy, well-connected Lincolnshire squire, who already had a record of violent behaviour, was a neighbour of Cromwell, and may have attacked Cromwell to protect himself from punishment for earlier crimes. Cromwell initiated legal action against Tailboys following the assault, but it was blocked by Suffolk, who was a patron of Tailboys. Outraged by Suffolk's actions, it seems that Cromwell set in motion the process of impeachment against Suffolk that was completed by the Commons in January 1450. The inclusion in the articles of impeachment of detailed financial information concerning Suffolk's administration suggests Cromwell's influence, and the mention of Tailboys among the charges against Suffolk reinforces the veracity of contemporary reports of Cromwell's efforts against Suffolk. Suffolk was subsequently murdered crossing the channel, and Tailboys was placed in the Tower of London while the legal proceedings against him ran their courses. He was convicted in February 1450 of the charges brought against him by Cromwell, and was ordered to pay damages of £2000. Tailboys did not, however, abandon his efforts to destroy Cromwell, and in 1451 and 1452 he used rumours and bills to accuse Cromwell of being a party to the loss of English lands in France, in what amounted to a campaign of character assassination against him. Cromwell's reappointment as king's chamberlain in the summer of 1450 made him seem more a part of an unpopular government than he actually was, or recently had been—there is little evidence for friendship between Cromwell and Edmund Beaufort, duke of Somerset (d. 1455), who was emerging as the king's principal councillor. The links between Cromwell and the duke of York served to diminish Cromwell's influence at the centre of power. He was suspected by the council of being involved in York's rising of February 1452, and he was suspended from the council for several months in late 1452 and early 1453 until he could clear himself. Nor was this his only difficulty. A quarrel of several years' standing between himself and Henry Holland, duke of Exeter (d. 1475), over lands in Bedfordshire became extremely bitter in 1452, with outbreaks of violence in June 1452 and again the following spring. In an effort to retrieve his position, Cromwell established ties with the Neville family and strengthened his connection with the duke of York. Cromwell was childless, and his heirs were his two nieces, the daughters of his sister Maud. One of those nieces, Maud Stanhope, widow of Robert (III), sixth Lord Willoughby of Eresby (d. 1452), was married in the summer of 1453 to Sir Thomas Neville, second son of Richard Neville, earl of Salisbury (d. 1460). In the same summer Cromwell became a feoffee of lands to York's use. The connection with York made Cromwell less tolerable to Somerset, and this in turn tied Cromwell's fate more closely to York's. Thus Cromwell could hope to benefit when, following Henry VI's collapse into insanity in August 1453, York was appointed protector and defender of the realm on 27 March 1454. And with his patron he came under threat when the king recovered his senses and Somerset returned to power at the end of 1454. York took up arms, and on 22 May 1455 defeated and killed Somerset at the first battle of St Albans. Cromwell arrived on the scene the day after the battle, and his tardiness may indicate that he had misgivings about York's violent courses. York was subsequently appointed protector again on 19 November, and it was during this second protectorate that Cromwell died at his Derbyshire manor of South Wingfield on 4 January 1456. Cromwell as builder Cromwell's activity in public life was complemented by equal activity as a builder. Without children to provide for, and comfortably wealthy, he was able to finance some impressive architectural projects. The southernmost of these was Collyweston in Northamptonshire, of which today nothing remains although the site is well established. Here he considerably augmented a house which he purchased in 1441, and which had been begun earlier in the century by Sir William Porter. South Wingfield, an impressive stone manor house overlooking the Amber valley, was built by Cromwell over a decade, or perhaps longer, beginning in 1439 or 1440. A building account for the period from 1 November 1442 to Christmas 1443 notes expenditures of £222 16s. 11¾d., but this in no way represents the total cost of construction, of which impressive remains can still be seen. Cromwell also had a manor house at Lambley, Nottinghamshire, which had been in the family since the eleventh century, but nothing remains of it today. The parish church of Lambley was the final resting place of his parents and grandparents, and perhaps of other ancestors as well. Cromwell left instructions in his testament that the church be rebuilt from his estate, and that a marble slab with brass images of his parents be placed over their grave. The rebuilding was carried out under the direction of his executors after his death. At Tattershall, where he had inherited an early thirteenth-century castle, Cromwell undertook to build or refurbish an entire complex of buildings, and to make this his principal residence. The centrepiece of the domestic buildings was, and remains, an imposing brick tower begun in 1434 and completed in 1446. The tower-house was built on six levels, and was designed for the comfort of its owner, and also to provide a dramatic expression of his distinction and power. Within the castle the surviving chimney-pieces suggest a taste for sumptuous display as well as family pride, for they are carved with heraldic shields of Cromwell and kindred families, and also with pouch-like purses, a favourite decorative device probably representing Cromwell's eminence as treasurer of England. Beyond the castle moat Cromwell founded a college of seven chantry chaplains, for which he obtained a charter in 1440. The old parish church was not adequate for Cromwell's grander purposes, and it was taken down to make way for a new stone-built church dedicated to the Holy Trinity. Cromwell and his wife were buried in the church, and their canopied memorial brass, though damaged, remains one of the most impressive in Lincolnshire. In addition to the chantry chaplains using the choir of Holy Trinity (the nave was for parochial use), the ecclesiastical personnel included six secular clerks and six choristers, and two brick lodgings were constructed for all these men. There were also built two bede-houses or almshouses, with hall and chapel, for thirteen elderly poor men and the same number of women. If Lord Cromwell wished to leave a physical legacy of his life and eminence, it must be admitted that he succeeded. A. C. Reeves Sources A. Emery, ‘Ralph Lord Cromwell's manor at Wingfield, 1439–1450: its construction, design and influence’, Archaeological Journal, 142 (1985), 276–339 · R. L. Friedrichs, ‘The career and influence of Ralph Lord Cromwell, 1393–1456’, PhD diss., Columbia University, 1974 · R. L. Friedrichs, ‘Ralph Lord Cromwell and the politics of fifteenth century England’, Nottingham Medieval Studies, 32 (1988), 207–27 · R. L. Friedrichs, ‘The two last wills of Ralph, Lord Cromwell’, Nottingham Medieval Studies, 34 (1990), 1–20 · J. L. Kirby, ‘The issues of the Lancastrian exchequer and Lord Cromwell's estimates of 1433’, BIHR, 24 (1951), 121–51 · R. Marks, ‘The glazing of the collegiate church of the Holy Trinity, Tattershall (Lincs.): a study of late fifteenth-century glass-painting workshops’, Archaeologia, 106 (1979), 133–56 · R. Marks, ‘The rebuilding of Lambley church, Nottinghamshire’, Transactions of the Thoroton Society, 87 (1983), 87–9 · E. M. Myatt-Price, ‘Ralph Lord Cromwell, 1394–1456’, Lincolnshire Historian, 11/4 (1957), 4–13 · S. Payling, Political society in Lancastrian England (1991) · [J. Raine], ed., Testamenta Eboracensia, 2, SurtS, 30 (1855), 196–200 · W. D. Simpson, ed., The building accounts of Tattershall Castle, 1434–1472, Lincoln RS, 55 (1960) · M. W. Thompson, ‘The architectural significance of the building works of Ralph, Lord Cromwell, 1394–1456’, Collectanea historica: essays in memory of Stuart Rigold, ed. A. P. Detsicas, Kent Archaeological Society (1981) · M. W. Thompson, ‘The construction of the manor at South Wingfield, Derbyshire’, Problems in economic and social archaeology, ed. G. de G. Sieveking, I. H. Longworth, and K. E. Wilson (1976), 417–37 · M. W. Thompson, Tattershall Castle, Lincolnshire (1974) · R. Virgoe, ‘William Tailboys and Lord Cromwell: crime and politics in Lancastrian England’, Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library, 55 (1972–3), 459–82 · C. Weir, ‘The site of the Cromwells' mediaeval manor house at Lambley, Nottinghamshire’, Transactions of the Thoroton Society, 85 (1981), 75–7 · K. B. McFarlane, The nobility of later medieval England (1973), 49 · K. B. McFarlane, ‘The Wars of the Roses’, England in the fifteenth century: collected essays (1981), 231–61, esp. 240, n.21 · PRO, chancery, early chancery proceedings, CI · PRO, special collections, rentals and surveys, SC 11 · PRO, exchequer, king's remembrancer, accounts various, E 101 Archives Magd. Oxf. · Sheffield Central Library, estate records and records of public service | CKS, De L'Isle and Dudley MSS · Sheff. Arch., Copley deeds Wealth at death over £21,000: McFarlane, England, 240, n.21 © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press A. C. Reeves, ‘Cromwell, Ralph, third Baron Cromwell (1393?-1456)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/6767, accessed 23 Sept 2005] Ralph Cromwell (1393?-1456): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6767 Back to top of biography Site credits | |

| Residence* | Tattershall, Lincolnshire, England8 | |

| Summoned* | 28 December 1375 | England, Parliament8,1 |

| (Witness) Death | circa 1382 | | leaving her cousin, Ralph Cromwell, as her heir, Principal=Thomasine Belers1 |

| Event-Misc* | from 1386 to 1387 | He was a Banneret, retained to serve the King in the event of invasion.1 |

| Event-Misc* | 1394 | They obtained a papal indult to celebrate mass before daybreak, Principal=Maud Bernacke1 |

Family | Maud Bernacke b. bt 1335 - 1338, d. 10 Apr 1419 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 23 Sep 2005 |

Citations

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Marmion 9.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-34.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 138-7.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-34.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-32.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 132-8.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 87.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-35.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-33.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-36.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 132-9.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Fitzwilliam 9.

- [S285] Leo van de Pas, 30 Jun 2004.

Maud Bernacke

F, #1716, b. between 1335 and 1338, d. 10 April 1419

| Father* | Sir John Bernacke b. bt 1305 - 1306, d. 20 Mar 1346; daughter and heir1,2,3,4 | |

| Mother* | Joan Marmion1,2 d. 2 Oct 1361 or 13 Oct 1361 | |

Maud Bernacke|b. bt 1335 - 1338\nd. 10 Apr 1419|p58.htm#i1716|Sir John Bernacke|b. bt 1305 - 1306\nd. 20 Mar 1346|p58.htm#i1717|Joan Marmion|d. 2 Oct 1361 or 13 Oct 1361|p58.htm#i1718|Sir William Bernake|d. Apr 1339|p379.htm#i11356|Alice de Driby||p379.htm#i11355|Sir John Marmion|b. c 1292\nd. 30 Apr 1335|p58.htm#i1722|Maud de Furnival||p58.htm#i1721| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | between 1335 and 1338 | 5 |

| Marriage* | before 20 January 1360/61 | Principal=Sir Ralph Cromwell5 |

| Marriage | before 20 June 1366 | Conflict=Sir Ralph Cromwell1,6,3 |

| Death* | 10 April 1419 | 1,5 |

| Name Variation | Maud de Bernak5 | |

| (Witness) Death | circa 1360 | | leaving his sister Maud as his heir, Principal=William de Bernak5 |

| Married Name | Cromwell | |

| Event-Misc* | 1394 | They obtained a papal indult to celebrate mass before daybreak, Principal=Sir Ralph Cromwell5 |

| Event-Misc* | 1394 | She was co-heiress to her cousin, Mary Percy, wife of John Roos5 |

Family | Sir Ralph Cromwell d. 27 Aug 1398 | |

| Children | ||

| Last Edited | 20 Nov 2004 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-32.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 132-7.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 87.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Fitzwilliam 9.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Marmion 9.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 132-8.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-33.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 210-36.

- [S285] Leo van de Pas, 30 Jun 2004.

Sir John Bernacke

M, #1717, b. between 1305 and 1306, d. 20 March 1346

| Father* | Sir William Bernake1,3,2 d. Apr 1339 | |

| Mother* | Alice de Driby1,2 | |

Sir John Bernacke|b. bt 1305 - 1306\nd. 20 Mar 1346|p58.htm#i1717|Sir William Bernake|d. Apr 1339|p379.htm#i11356|Alice de Driby||p379.htm#i11355|||||||Sir Robert de Driby|d. 1279|p379.htm#i11357|Joan de Tateshal|b. c 1256|p379.htm#i11358| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | between 1305 and 1306 | 2 |

| Birth | 1309 | 4 |

| Marriage* | 1st=Joan Marmion4,5,3,2 | |

| Death* | 20 March 1346 | 2 |

| Death | 1349 | 4 |

| Feudal* | Tattershall, Lincolnshire, and Bokenham2 |

Family | Joan Marmion d. 2 Oct 1361 or 13 Oct 1361 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 20 Nov 2004 |

Citations

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 132-6.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Marmion 8.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 87.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-31.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 132-7.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Marmion 9.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-32.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Fitzwilliam 9.

Joan Marmion

F, #1718, d. 2 October 1361 or 13 October 1361

| Father* | Sir John Marmion b. c 1292, d. 30 Apr 1335; daughter and heir1,2 | |

| Mother* | Maud de Furnival | |

Joan Marmion|d. 2 Oct 1361 or 13 Oct 1361|p58.htm#i1718|Sir John Marmion|b. c 1292\nd. 30 Apr 1335|p58.htm#i1722|Maud de Furnival||p58.htm#i1721|Sir John Marmion|b. c 1255\nd. b 7 May 1322|p58.htm#i1719|Isabel (?)|d. 1314|p58.htm#i1720|Sir Thomas de Furnival|b. c 1270\nd. 3 Feb 1332|p84.htm#i2514|Joan le Despenser|b. c 1259\nd. b 8 Jun 1322|p84.htm#i2515| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | Groom=Sir John Bernacke1,3,2,4 | |

| Marriage* | before 1360 | Principal=Sir John de Folville4 |

| Death* | 2 October 1361 or 13 October 1361 | 4 |

| Death | 1362 | 1 |

| Married Name | Bernacke5 | |

| Event-Misc* | before 1360 | Joan Marmion was heir to her brother, Robert Marmion, by which she inherited a 1/2 share in the manors of Lutton, Northamptonshire, and Wath, Hunmanby, and Langton-on-Swale, Yorkshire, Witness=Robert Marmion4 |

Family | Sir John Bernacke b. bt 1305 - 1306, d. 20 Mar 1346 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 13 Oct 2004 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-31.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 87.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 132-7.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Marmion 8.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-32.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Marmion 9.

Sir John Marmion1

M, #1719, b. circa 1255, d. before 7 May 1322

| Father* | Sir William Marmion2 b. a 1223, d. b 1276 | |

| Mother* | Lorette of Dover2 | |

Sir John Marmion|b. c 1255\nd. b 7 May 1322|p58.htm#i1719|Sir William Marmion|b. a 1223\nd. b 1276|p58.htm#i1723|Lorette of Dover||p58.htm#i1724|Robert Marmion The Younger||p58.htm#i1725|Avice D. Tanfield||p58.htm#i1726|Richard FitzRoy|d. b 24 Jun 1246|p58.htm#i1727|Rohese of Dover|d. 1265|p58.htm#i1728| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | circa 1255 | 3 |

| Marriage* | 2nd=Isabel (?)2,3 | |

| Death* | before 7 May 1322 | 2,1,3 |

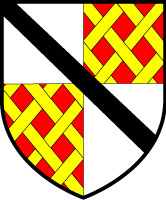

| Arms* | De veer a une fesse de goules (Parl.) Vair a fesse gu. (1 Nob). Vair nebuly a fess gu. (Guillim).1 | |

| Name Variation | Marmyon1 | |

| Feudal* | 1278 | one Kt. Fee in Suss., he is distrained for Kthood.4 |

| Event-Misc* | 2 November 1281 | Son of Wm. Marmyon, he has quittance of £7 19s. that his father took from the Sheriff of Yorks. in the disturbances t. Hen III (C. R.)4 |

| Feudal | 4 December 1282 | Messingham Manor, Lincolnshire4 |

| Feudal | 20 May 1290 | Hewyk, Yorkshire4 |

| Feudal | 5 December 1291 | Berewyke Manor, Suss., as 1 1/2 Kt. Fee, with 4 Fees at Wintringham and Wolingham, 1 Fee at Kyseby (Kexby), and 1/4 Fee at Trickingham and Stowe, Lincs., late of Philip Marmyon4 |

| Event-Misc | 14 June 1294 | Excepted from service in Gascony1 |

| Summoned* | 1297 | Salisbury, Parliament1 |

| Summoned | 7 July 1297 | serve overseas, having £20 lands in Suss. and Surr.1 |

| Summoned | 8 September 1297 | Rochester, Council1 |

| Event-Misc | 1298 | Knight of the Shire for Lincolnshire1 |

| Event-Misc | 24 June 1300 | serve against the Scots, having £40 lands in Glou. and Lincs. and Yorks.1 |

| Event-Misc | 1303 | serve under John de Segrave, Witness=Sir John de Segrave1 |

| Event-Misc | 23 September 1304 | The Sheriff of Lincs. is to perambulate the bounds of his lands and Wintringham and those of Alice de Lacy at Halton on Trent.1 |

| Event-Misc* | 23 July 1310 | Lic. for John Marmyon to alienate mess., lands, and rents at Wyntringham and Belesby, Lincs., for a chaplain to celebrate daily in St. Nicholas Chapel, Wintringham, for souls of himself and w. Isabella, Alex. Peck, and their ancestors and successors, Principal=Isabel (?)1 |

| Protection* | 3 May 1313 | overseas with the King1 |

| Summoned | from 23 September 1313 to 2 May 1322 | Parliament3 |

| Event-Misc | 8 February 1314 | Jn. Marmyon, sen. and jun., and others accused by Abbot of Fountains of felling his trees at Aldeburgh, Yorks., taking 200 sheep at Melmorby, 10 oxen from his ploughs at Wathe, 4 iron-bound wains laden with hay, and 40 oxen yoked thereto, a horse laden with plough-irons going to be mended, impounding some of them, assaulting his men, plucking out their beards and cutting them with knives., Principal=Sir John Marmion1 |

| Feudal | 24 September 1314 | Lic. to crenellate his dwelling place called Lermitage in his wood of Tanfeld, Yorks.1 |

| Summoned | 6 January 1315 | defend counties N. of Trent against the Scots1 |

| Feudal | 5 March 1316 | Quinton, Glou., Lutton, Warmyngton, and Lullington, Northants., Petcham, Hailsham, and Berwick, Suss., Stanwick, Lit. Langton, Burgh, Manfield, E. and W. Tanfield, Winton, Nosterfeld, Sinderby, Exilby, Newton, Leming, and Carthorp, Yorks.1 |

| Event-Misc | 14 April 1317 | Lic to alienate to the parson of Scryvelby, Lincs., a plot of land for enlargement of the rectory house1 |

| Event-Misc | 14 November 1321 | Jn. M., sen., and others accused of trespass against the Abbot of Rewley at Nettlebed, Oxon., and taking his trees1 |

Family | Isabel (?) d. 1314 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 31 Dec 2004 |

Isabel (?)

F, #1720, d. 1314

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | Groom=Ralph de Plaiz1 | |

| Marriage* | Groom=Sir John Marmion2,1 | |

| Death* | 1314 | 1 |

| Event-Misc* | 23 July 1310 | Lic. for John Marmyon to alienate mess., lands, and rents at Wyntringham and Belesby, Lincs., for a chaplain to celebrate daily in St. Nicholas Chapel, Wintringham, for souls of himself and w. Isabella, Alex. Peck, and their ancestors and successors, Principal=Sir John Marmion3 |

| Married Name | Marmion |

Family | Sir John Marmion b. c 1255, d. b 7 May 1322 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 13 Oct 2004 |

Maud de Furnival

F, #1721

| Father* | Sir Thomas de Furnival1 b. c 1270, d. 3 Feb 1332 | |

| Mother* | Joan le Despenser2,3 b. c 1259, d. b 8 Jun 1322 | |

Maud de Furnival||p58.htm#i1721|Sir Thomas de Furnival|b. c 1270\nd. 3 Feb 1332|p84.htm#i2514|Joan le Despenser|b. c 1259\nd. b 8 Jun 1322|p84.htm#i2515|Thomas de Furnival|b. 1229\nd. 12 May 1291|p84.htm#i2520||||Sir Hugh le Despenser|b. 1223\nd. 4 Aug 1265|p84.htm#i2516|Aline Basset|b. 1245\nd. b 11 Apr 1281|p84.htm#i2517| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | Principal=Sir John Marmion4 | |

| Married Name | Marmion4 | |

| Living* | 1348 | 5 |

| Event-Misc* | 1362 | John of Gaunt granted license in mortmain for the grant of land in the Manors of West Tanfield and Carthrope to certain chaplains to celebrate in the church of West Tanfield for the good of his soul and the souls of John Marmion and Maud, his wife., Principal=Sir John Marmion, Witness=John of Gaunt (?)2 |

Family | Sir John Marmion b. c 1292, d. 30 Apr 1335 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 3 Apr 2005 |

Citations

Sir John Marmion

M, #1722, b. circa 1292, d. 30 April 1335

| Father* | Sir John Marmion b. c 1255, d. b 7 May 1322; son and heir1,2 | |

| Mother* | Isabel (?)3,2 d. 1314 | |

Sir John Marmion|b. c 1292\nd. 30 Apr 1335|p58.htm#i1722|Sir John Marmion|b. c 1255\nd. b 7 May 1322|p58.htm#i1719|Isabel (?)|d. 1314|p58.htm#i1720|Sir William Marmion|b. a 1223\nd. b 1276|p58.htm#i1723|Lorette of Dover||p58.htm#i1724||||||| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | circa 1292 | 1,4 |

| Marriage* | Principal=Maud de Furnival1 | |

| Death* | 30 April 1335 | 1,4 |

| Event-Misc* | 16 October 1313 | pardoned re Gaveston, Witness=Piers de Gaveston5 |

| Event-Misc | 8 February 1314 | Jn. Marmyon, sen. and jun., and others accused by Abbot of Fountains of felling his trees at Aldeburgh, Yorks., taking 200 sheep at Melmorby, 10 oxen from his ploughs at Wathe, 4 iron-bound wains laden with hay, and 40 oxen yoked thereto, a horse laden with plough-irons going to be mended, impounding some of them, assaulting his men, plucking out their beards and cutting them with knives., Principal=Sir John Marmion5 |

| Summoned* | 30 June 1314 | serve against the Scots5 |

| Event-Misc | 2 June 1322 | Accused with others of entering Manors of John de Haudlo in Bucks. and taking cattle.5 |

| Protection* | 5 August 1322 | to Scotland for the King with John, Earl of Richmond.5 |

| Event-Misc | 31 October 1322 | Commissioner of Array for Yorkshire, to arm men between 16 and 60 of N. Riding, muster them at York, and provide them if necessary with pack saddles5 |

| Summoned | 9 May 1324 | the Great Council at Westminster as a Knight of Glou., Lincs., and Yorks.5 |

| Summoned | 20 February 1325 | serve in Guienne5 |

| Event-Misc* | 30 May 1326 | Anthony de Lucy owes John Marmyon 400 m. in Cumb., Westmd., and Northumb., Principal=Anthony de Lucy5 |

| Occupation* | 2 October 1326 | Yorkshire, a justice5 |

| Summoned | 3 December 1326 | Parliament5,4 |

| Protection | May 1329 | to the Holy Land4 |

| Event-Misc | 1362 | John of Gaunt granted license in mortmain for the grant of land in the Manors of West Tanfield and Carthrope to certain chaplains to celebrate in the church of West Tanfield for the good of his soul and the souls of John Marmion and Maud, his wife., Principal=Maud de Furnival, Witness=John of Gaunt (?)4 |

Family | Maud de Furnival | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 20 Jan 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-30.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Marmion 6.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-29.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Marmion 7.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 3, p. 120.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-31.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, p. 87.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Oddingseles 7.

- [S338] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 8th ed., 219-31.

Sir William Marmion

M, #1723, b. after 1223, d. before 1276

| Father* | Robert Marmion The Younger; son and heir1,2 | |

| Mother* | Avice De Tanfield3,2 | |

Sir William Marmion|b. a 1223\nd. b 1276|p58.htm#i1723|Robert Marmion The Younger||p58.htm#i1725|Avice De Tanfield||p58.htm#i1726|||||||Gernegan Fitzhugh of Tanfield||p473.htm#i14164|||| | ||

| Birth* | after 1223 | (he was still a minor in 1243)2 |

| Marriage* | before 7 June 1248 | Principal=Lorette of Dover3,4 |

| Death* | before 1276 | 3 |

| Feudal | Tanfield, Yorkshire, Butterwick and Messingham, Lincolnshire, and Winton and Berwick, Sussex, and in right of his wife, Lutton, Northamptonshire.2 | |

| Battle-Lewes* | 5 | |

| Arms* | De verree ung fesse de goulez5 | |

| Protection* | 28 October 1259 | to France with the King for Wm. fil. Wm. Marmiun and Wm. fil. Rob. M.5 |

| Event-Misc | 10 January 1266 | Safe conduct coming to the King's court, provided he stand his trial5 |

| Event-Misc | 1 July 1267 | Admitted to the Kings peace5 |

| Event-Misc | 10 October 1267 | His lands were given to Rob. Aguillon, but may be ransomed. His chief lord, Philip Marmyon, makes himself principal debtor for the money.5 |

| Feudal* | 10 August 1268 | 1/4 Kt. Fee at Upton, Glou., late of Richard, E. of Gloucester.5 |

| Event-Misc* | 20 February 1275 | From the Close Roll: Sir Wm. de Say seized his Manor of Berewik, Suss. The Earl of Gloucester's men came and hold it still. Wm. M. was a rebel. His lands at Wintringham, Lincs., are worth £9 15s. 8d., at Botrewik £1 16s., at Messingtham £9 2s. Wm. M. was with Sir Simon de Montfort at Evesham. He Married the wid. of Sir Rob. de Mars, who held custody of Esseby Manor, Northants., val £12. Gilb. de Clare seized it. He and others hindered the Sheriff of Yorks. from his office from Mich. 48 Hen III till battle of Lewes.5 |

Family | Lorette of Dover | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 31 Dec 2004 |

Lorette of Dover

F, #1724

| Father* | Richard FitzRoy d. b 24 Jun 1246 | |

| Mother* | Rohese of Dover1,2 d. 1265 | |

Lorette of Dover||p58.htm#i1724|Richard FitzRoy|d. b 24 Jun 1246|p58.htm#i1727|Rohese of Dover|d. 1265|p58.htm#i1728|John Lackland|b. 27 Dec 1166\nd. 19 Oct 1216|p54.htm#i1620|Anonyma de Warenne||p58.htm#i1730|Fulbert of Dover||p58.htm#i1729|Isabel de Briwere|b. c 1184\nd. b 10 Jun 1233|p138.htm#i4130| | ||

| Marriage* | before 7 June 1248 | Principal=Sir William Marmion1,3 |

| Name Variation | Lora de Chilham4 | |

| Married Name | Marmion |

Family | Sir William Marmion b. a 1223, d. b 1276 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 20 Nov 2004 |

Robert Marmion The Younger

M, #1725

| Marriage* | Principal=Avice De Tanfield1,2 |

Family | Avice De Tanfield | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 13 Oct 2004 |

Avice De Tanfield

F, #1726

| Father* | Gernegan Fitzhugh of Tanfield1 | |

Avice De Tanfield||p58.htm#i1726|Gernegan Fitzhugh of Tanfield||p473.htm#i14164|||||||||||||||| | ||

| Marriage* | Principal=Robert Marmion The Younger2,1 | |

| Married Name | Marmion2 |

Family | Robert Marmion The Younger | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 13 Oct 2004 |

Richard FitzRoy

M, #1727, d. before 24 June 1246

|

| Father* | John Lackland b. 27 Dec 1166, d. 19 Oct 1216; bastard1,2 | |

| Mother* | Anonyma de Warenne1,3 | |

Richard FitzRoy|d. b 24 Jun 1246|p58.htm#i1727|John Lackland|b. 27 Dec 1166\nd. 19 Oct 1216|p54.htm#i1620|Anonyma de Warenne||p58.htm#i1730|Henry I. Curtmantel|b. 5 Mar 1132/33\nd. 6 Jul 1189|p55.htm#i1622|Eleanor of Aquitaine|b. 1123\nd. 31 Mar 1204|p55.htm#i1623|Sir Hamelin Plantagenet|b. c 1130\nd. 7 May 1202|p70.htm#i2077|Isabel de Warene|b. c 1137\nd. 12 Jul 1203|p101.htm#i3002| | ||

| Marriage* | before 11 May 1214 | Principal=Rohese of Dover1,3,4,5 |

| Death* | before 24 June 1246 | 3 |

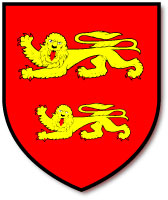

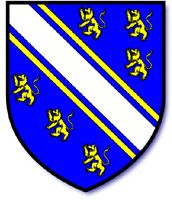

| Arms* | Gu. 2 lions passant gardant or. (Dering).4 | |

| Name Variation | de Warenne5 |

Family | Rohese of Dover d. 1265 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 29 Dec 2004 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-27.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Plantagenet 3.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 107.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Atholl 4.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 26-28.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Atholl 5.

Rohese of Dover

F, #1728, d. 1265

| Father* | Fulbert of Dover1,2,3 | |

| Mother* | Isabel de Briwere2,3 b. c 1184, d. b 10 Jun 1233 | |

Rohese of Dover|d. 1265|p58.htm#i1728|Fulbert of Dover||p58.htm#i1729|Isabel de Briwere|b. c 1184\nd. b 10 Jun 1233|p138.htm#i4130|||||||William de Briwere|b. c 1145\nd. 1226|p139.htm#i4161|Beatrice de Vaux||p139.htm#i4162| | ||

| Birth* | of Chilham, Kent, England2 | |

| Marriage* | before 11 May 1214 | Principal=Richard FitzRoy1,2,4,3 |

| Death | before 11 February 1261 | 2 |

| Death* | 1265 | 1 |

| Name Variation | Rose de Douvres3 |

Family | Richard FitzRoy d. b 24 Jun 1246 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 20 Nov 2004 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-27.

- [S218] Marlyn Lewis, Ancestry of Elizabeth of York.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Atholl 4.

- [S325] Rev. C. Moor, Knights of Edward I, v. 4, p. 107.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 218-28.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 26-28.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Atholl 5.

Fulbert of Dover

M, #1729

| Marriage* | 1st=Isabel de Briwere1,2 |

Family | Isabel de Briwere b. c 1184, d. b 10 Jun 1233 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 20 Nov 2004 |

Anonyma de Warenne1

F, #1730

| Father* | Sir Hamelin Plantagenet2,3 b. c 1130, d. 7 May 1202 | |

| Mother* | Isabel de Warene2 b. c 1137, d. 12 Jul 1203 | |

Anonyma de Warenne||p58.htm#i1730|Sir Hamelin Plantagenet|b. c 1130\nd. 7 May 1202|p70.htm#i2077|Isabel de Warene|b. c 1137\nd. 12 Jul 1203|p101.htm#i3002|Geoffrey V. "the Fair" Plantagenet|b. 24 Nov 1113\nd. 7 Sep 1151|p55.htm#i1624|Anonyma (?)||p457.htm#i13698|Sir William de Warenne|b. 1118\nd. 31 Mar 1148|p101.htm#i3004|Ela Talvas|b. c 1120\nd. 4 Oct 1174|p101.htm#i3005| | ||

| Mistress* | Principal=John Lackland3,2,4 | |

| Name Variation | (?) de Warenne4 |

Family | John Lackland b. 27 Dec 1166, d. 19 Oct 1216 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 5 Sep 2005 |

Margaret le Despencer

F, #1731, d. 3 November 1415

|

| Father* | Sir Edward le Despenser K.G., M.P.1,2,3,4 b. 24 Mar 1335/36, d. 11 Nov 1375 | |

| Mother* | Elizabeth de Burghersh1,4 b. 1342, d. c 26 Jul 1409 | |

Margaret le Despencer|d. 3 Nov 1415|p58.htm#i1731|Sir Edward le Despenser K.G., M.P.|b. 24 Mar 1335/36\nd. 11 Nov 1375|p89.htm#i2646|Elizabeth de Burghersh|b. 1342\nd. c 26 Jul 1409|p89.htm#i2647|Sir Edward le Despenser|d. 30 Sep 1342|p90.htm#i2673|Anne de Ferrers|d. 8 Aug 1367|p90.htm#i2674|Sir Bartholomew de Burghersh K.G.|b. s 1323\nd. 5 Apr 1369|p89.htm#i2648|Cicely de Weyland|b. c Apr 1319|p89.htm#i2649| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Marriage* | after 1379 | 2nd=Sir Robert de Ferrers5,6,2,7,4 |

| Death* | 3 November 1415 | 8,6,7,4 |

| Burial* | Merevale Abbey, England5,7,4 | |

| (Witness) Will | 1409 | bequeathing two chargers and twelve dishes of silver to daughter Margaret, Principal=Elizabeth de Burghersh9 |

Family | Sir Robert de Ferrers b. 31 Oct 1357 or 31 Oct 1359, d. 12 Mar 1413 or 13 Mar 1413 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 9 Oct 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 70-35.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 13-9.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Clare 9.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Ferrers 11.

- [S183] Jr. Meredith B. Colket, Marbury Ancestry, p. 40.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 115-8.

- [S234] David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry, Ferrers 10.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 61-34.

- [S374] Douglas Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry, Ferrers 8.

Margaret de Audley

F, #1732, b. before 1325, d. 7 September 1349

| Father* | Sir Hugh de Audley b. c 1289, d. 10 Nov 1347; daughter and heir1,2,3,4 | |

| Mother* | Margaret de Clare1 b. c 1292, d. 9 Apr 1342 | |

Margaret de Audley|b. b 1325\nd. 7 Sep 1349|p58.htm#i1732|Sir Hugh de Audley|b. c 1289\nd. 10 Nov 1347|p92.htm#i2731|Margaret de Clare|b. c 1292\nd. 9 Apr 1342|p91.htm#i2729|Sir Hugh de Audley|b. c 1267\nd. bt Nov 1325 - Mar 1326|p92.htm#i2732|Isolde de Mortimer|b. bt 1255 - 1260\nd. b 4 Aug 1338|p92.htm#i2733|Sir Gilbert de Clare "the Red"|b. 2 Sep 1243\nd. 7 Dec 1295|p69.htm#i2059|Joan of Acre|b. Spring 1272\nd. 23 Apr 1307|p70.htm#i2074| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth | between 1322 and 1324 | 4 |

| Birth* | before 1325 | 5 |

| Marriage* | before 6 July 1336 | Sir Ralph abducted Margaret and they were married against her father's will., 2nd=Sir Ralph de Stafford K.G.6,5,7,2,3,4,8 |

| Death* | 7 September 1349 | 5,4 |

| Burial* | Tonbridge, Kent, England4,8 |

Family | Sir Ralph de Stafford K.G. b. 24 Sep 1301, d. 31 Aug 1372 | |

| Children |

| |

| Last Edited | 26 Jan 2005 |

Citations

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 9-30.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Talbot 10.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Ferrers 10.

- [S284] Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, Stafford 9.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 9-31.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 61-33.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 115-7.

- [S301] Carl Boyer 3rd, Medieval English Ancestors of Robert Abell, p. 9.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 30-7.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 9-32.

- [S168] Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, 10-32.

- [S233] Frederick Lewis Weis, Magna Charta Sureties, 136-7.

Joan de la Mote1

F, #1733, d. 29 June 1375

| Marriage* | before 1350 | 2nd=Sir Robert de Ferrers1,2 |

| Death* | 29 June 1375 | London, Middlesex, England1,2 |

| Event-Misc* | 1352 | She received a papal indult for plenary remission2 |

Family | Sir Robert de Ferrers b. 25 Mar 1309, d. 28 Aug 1350 | |

| Child |

| |

| Last Edited | 15 Oct 2004 |

Sir Robert de Ferrers

M, #1734, b. 1239, d. 27 April 1279

|

| Father* | Sir William de Ferrers b. c 1193, d. 24 Mar 1254 or 28 Mar 1254; son and heir1,2 | |

| Mother* | Margaret de Quincy1,3 b. b 1223, d. b 12 Mar 1280/81 | |

Sir Robert de Ferrers|b. 1239\nd. 27 Apr 1279|p58.htm#i1734|Sir William de Ferrers|b. c 1193\nd. 24 Mar 1254 or 28 Mar 1254|p58.htm#i1736|Margaret de Quincy|b. b 1223\nd. b 12 Mar 1280/81|p58.htm#i1737|Sir William de Ferrers Earl of Derby|b. c 1168\nd. 22 Sep 1247|p90.htm#i2688|Agnes of Chester|b. c 1174\nd. 2 Nov 1247|p90.htm#i2689|Sir Roger de Quincy|b. c 1195\nd. 25 Apr 1264|p64.htm#i1912|Helene of Galloway|b. c 1196\nd. a 21 Nov 1245|p64.htm#i1913| | ||

| Charts | Ann Marbury Pedigree |

| Birth* | 1239 | 1,4,5 |

| Birth | circa 1241 | 2 |

| Marriage Contract* | 26 July 1249 | Westminster, (without issue), Bride=Mary de Lusignan6,3 |

| Marriage* | 26 June 1269 | Bride=Eleanor de Bohun7,4,3 |

| Death* | 27 April 1279 | Windsor Castle, shortly before 27 Apr 1279 | while being held prisoner1,3 |

| Burial* | St. Thomas Priory, Stafford, Staffordshire, England3 | |

| DNB* | Ferrers, Robert de, sixth earl of Derby (c.1239-1279), magnate and rebel, was the eldest son of William de Ferrers, earl of Derby (c.1200–1254), from his second marriage, to Margaret, elder daughter and coheir of Roger de Quincy, earl of Winchester (d. 1264). Childhood and inheritance Ferrers's first appearance as a public figure came in 1249, when he married the seven-year-old Mary, daughter of Hugues (XI) de Lusignan, count of La Marche, the eldest of Henry III's half-brothers, at Westminster—a match that marked Henry's regard for Ferrers's father, who, though prominent at court in the 1230s, was later prevented by incapacitating gout from playing much part in affairs. The death of William de Ferrers in 1254 left his young son already a knight but also a minor. Unable to inherit, he saw the wardship of his estates handed over to Edward, the king's eldest son, and then sold on to the queen and Peter of Savoy for 6000 marks in 1257. Only in 1260 did he do homage and take possession of his lands. His preceding wardship was merely one, and perhaps the least important, of the factors that weakened Ferrers's standing at his accession to the earldom. In the two decades preceding his father's death territorial acquisitions and efficient management had combined to enhance the family fortunes. The ancestral holdings of the Ferrers formed a compact block in north Staffordshire, south Derbyshire, and western Nottinghamshire, centred on the castle and borough of Tutbury. But the marriage of Robert's grandfather, William, to Agnes, sister and coheir of Ranulf (III), earl of Chester, had brought in extensive new lands after Ranulf's death in 1232. Chief among them were the castle and manor of Chartley, Staffordshire, all Lancashire between Ribble and Mersey, and other manors in Northamptonshire and Lincolnshire. By additionally developing boroughs and markets, exploiting the forests of Needwood and Duffield, keeping a tight hold on grants, and taking advantage of the rising prices and land values, which benefited all great landowners at this time, Ferrers's grandfather and father had been able to build up an estate worth some £1500 p.a. in the 1250s—an income that placed the earls of Derby among the half-dozen wealthiest of Henry III's nobles. Ferrers could not maintain this position. His resources were depleted, most damagingly by the dower of his mother, Margaret, who survived until 1281 and was in possession of the widow's traditional third, amounting to land worth some £500 and including, at least for a time, the major asset of Chartley. But the estate also had to provide for Ferrers's younger brother William, for his wife Mary, who held two manors in her own right under the terms of their marriage agreement, and to a lesser extent for Edward, who retained some family land beyond Earl Robert's coming of age. Add to these burdens the debts of nearly £800 which Ferrers took over from his father and for which the exchequer was pursuing him in 1262—obligations that probably explain his borrowing from the Jews—and it becomes clear that the new earl, if not poor, was certainly hard-pressed. During the period of his wardship his only income appears to have been the £100 p.a. that Henry had settled on him and his wife by way of a maritagium. Aggression, aggrandizement and imprisonment, 1260–1265 Ferrers's financial difficulties, together with a violent waywardness of character that was to mark his whole career, may help to account for his first actions as earl. According to the Burton annals, no sooner had he received his lands in 1260 than he ‘destroyed’ the priory of Tutbury, of which he was patron. A series of subsequent and sizeable grants to the priory may confirm the story, pointing to a guilty conscience and possible reparations. He made comparably unlawful encroachments on the rights of some leading tenants, while also exploiting more licitly his forests and boroughs, following the lines laid down by his father and grandfather. Derby's involvement with his estates, along with his youth, inexperience, and possibly his disability (he had inherited his family's liability to gout), do much to explain his absence from national politics during these early years. He took no part in the great baronial reforms of royal government in 1258–9, initiated before his majority, and until 1263 he spent much of his time on his lands, especially at Tutbury. Unlike the other earls he witnessed none of Henry III's charters in the early 1260s, though Henry must have reckoned him a royalist, for Derby was among those whom the king summoned in arms to London in October 1261, during his restoration to power. At some point in these early years he also kept company with the leading reformers, two of whom, Richard de Clare, earl of Gloucester, and Simon de Montfort, witnessed an undated charter in favour of his sister. But there is nothing here to indicate any firm commitment to one side or the other. That remained true even after Montfort's return to England in April 1263, as the leader of an armed rising against the king's friends, had made an uncommitted stance more difficult to maintain. Ostensibly Derby moved towards Montfort. He first saw action during the disorders of May and June, when the Dunstable annals record his seizure of ‘three castles’ belonging to Edward: probably the ‘Three Castles’, often so called, of Grosmont, Skenfrith, and Whitecastle, which lay towards the centre of the disturbances in the southern marches of Wales. He was with Montfort in London in December 1263 and took a leading part in the renewed war along the marches, which followed Louis IX's quashing of the provisions of Oxford in January 1264. His chief exploit came at Worcester, where in February he took the town, sacked the Jewish quarter, killed or imprisoned many Jews, and later carried off to Tutbury the bonds recording Jewish loans: retaliation perhaps by an enraged debtor. He then moved down the Severn to Gloucester, where Edward had taken the castle for the king. But a truce made by Henry de Montfort allowed Edward to slip away from Derby's clutches, much to his anger, and to retreat to his father Henry at Oxford, devastating Derby's valuable Berkshire manor of Stanford in the Vale en route. These events clarify Derby's motives during the barons' war: not support for reform, but hatred of Edward. Of no one was Edward more afraid, says Robert of Gloucester, describing their near confrontation at Gloucester. The origins of this explosive feud are unfortunately obscure, but they probably lay in Edward's ancestral claim to the Peverel inheritance in north Derbyshire, including the castle of the Peak, which Derby's grandfather had been made to surrender to the crown in 1222 and which had become part of Edward's apanage in 1254. Edward's wardship of Earl Robert's lands between 1254 and 1257, and his later retention of some holdings, may have compounded these resentments. Whatever its roots, the feud contributed powerfully to the national disorders that marked the spring and summer of 1264. In March Edward's men attacked Derby's lands in Staffordshire, taking Chartley Castle, and after the royalist victory at Northampton in April Edward himself was able to turn against his enemy, destroying Tutbury and extorting money from Derby's tenants. Derby was still regarded as a Montfortian, for Montfort made a long but vain wait for his arrival before setting out from London for the campaign that gave him victory over the king at Lewes in May 1264. But in fact he was solely concerned with his own interests. Edward's capture at Lewes gave those interests free rein for the first time, and Derby was now able to regain and augment all that he had lost. He overran the royal and Edwardian castles of Bolsover, Derbyshire, Horston, Derbyshire, and Tickhill, Yorkshire, joined in Baldwin Wake's attack on the royal castle of Fotheringhay, Northamptonshire, and in late June or early July crowned these successes with the capture of Edward's chief castle of the Peak. In the autumn a westward campaign apparently brought Edward's other great base at Chester into his hands. Having obliterated Edward's power in the north-west midlands, he seemed set to replace it with his own. But Derby's achievement had been possible only because of Edward's captivity and the preoccupation of the country's ruler, Simon de Montfort, with a threatened French invasion of southern England; and in the winter of 1264–5 both these circumstances changed. By November 1264 the danger of invasion had receded, leaving Montfort's supremacy unchallenged, and in the following month plans were devised for Edward's release. They entailed the surrender to Montfort of a large part of Edward's apanage, including Chester and the Peak, in exchange for less valuable lands elsewhere. By this scheme Montfort thus replaced Edward as Derby's chief rival, with a new and personal interest in reversing his recent territorial gains. This was accomplished adeptly and with surprising ease. In December Derby was summoned to the parliament arranged for mid-January 1265, and shortly afterwards called on to surrender the Peak. The summons to a parliament that otherwise comprised only staunch Montfortians was an almost blatant device to remove Derby from the scene of his triumphs and to open his lands, new and old, to a Montfortian takeover. It is a mark of Earl Robert's characteristic lack of political cunning that he fell into the trap, with predictable results. In February, during his parliamentary sojourn in London, he was arrested and sent to the Tower of London. The chronicles give differing reasons for his arrest: it was a gesture to Henry, who would have preferred to see him condemned to death for his spoliations, or a punishment for his breaches of the peace after Lewes, or a result of his collusion with the rebellious marchers. But the variety of explanations only shows how well Montfort had covered his tracks. The truth was that Derby's removal was essential to Montfort's territorial ambitions, and that it could be accomplished without much risk because the earl's violent self-seeking had left him friendless. Rebellion and ruin, 1265–1269 Montfort, however, had neither the time nor the opportunity to enjoy his gains. The new territories had probably been intended as an endowment for his eldest son, Henry, but there was local resistance, both from Derby's men and from Edward's, to their appropriation, and Montfort's death at Evesham in August 1265 cut short any hopes of their absorption into a family principality. After the battle Derby was released, and in December 1265 he came to terms with the king, offering the substantial fine of 1500 marks and a gold cup in return for Henry's pardon, his mediation in the earl's quarrel with Edward, and his guarantee of Derby's being spared disinheritance. Given the harsh treatment of the Montfortians, whose disinheritance had already been decided on, Henry's willingness to do more for Derby may seem surprising; but the activities of the earl's associates in thwarting Montfort's territorial schemes had prepared the way for a reconciliation, and the king needed both his money and his support in the north midlands. It was therefore all the more foolish of Derby to turn his back on what he was fortunate to have obtained. In May 1266 he joined a rebellious gathering of disinherited Montfortians under Baldwin Wake and John Deyville at Chesterfield, where they were surprised and routed by a royalist force. Weakened by gout, Derby was taken prisoner while his blood was being let. His reasons for risking all in this way are entirely unclear. He had lost some land, including Chartley, as a result of his recent escapades, but in no sense had he been disinherited. Yet he had now placed himself so much in the wrong as to be as exposed as he had been in February 1265. This time his isolation was the prelude to his ruin. The process was a gradual one. After his capture Derby was imprisoned at Windsor, where he remained until 1269. In the meantime, by a series of royal orders and grants made between June and August 1266, Henry's second son, Edmund, was given possession of his lands and goods. Although in July Edmund received a formal grant of the Derby lands in fee, the dictum of Kenilworth, proclaimed in October, continued to hold out the possibility of Earl Robert's restoration. He could have his lands back in return for a redemption payment of seven times their annual value: a multiplier so large that it placed the earl in an almost unique category among the disinherited, a category to match what the king regarded as the enormity of his offences. In this sequence of events there was muddle and confusion, and although Edmund had de facto possession of Derby's lands he could not yet reckon that his position was secure. This was not achieved until 1269, by arrangements that combined an extension of the principles of the dictum of Kenilworth with royal connivance at an illicit piece of private enterprise. On 1 May 1269 Earl Robert appeared before king and council at Windsor. There he received back all his lands, acknowledged a debt of £50,000 to Edmund, and conceded that this sum should be raised from his lands if it had not been paid by 9 July. Disinheritance was not mentioned nor ostensibly intended. Later in the same day, however, he was taken to the manor of Cippenham, Buckinghamshire, the property of Richard, earl of Cornwall, and there, under duress (as he later pleaded) and in the presence of John Chishall, the chancellor, he made over all his lands to eleven manucaptors, all notable royalists, as a security for the payment of his £50,000 debt. He was then taken to Richard of Cornwall's castle at Wallingford and released at the end of May. When the deadline of 9 July passed without payment, as had, of course, been intended, the manucaptors transferred the estate to Edmund, and Ferrers was left virtually landless and deprived of his title. Attempts at recovery, and death For the remaining ten years of his life Ferrers's central interest lay in regaining his inheritance. This was a vain hope, largely because it would have meant dispossessing Henry III's second son and Edward I's brother (and finding other lands for him elsewhere), because king and council had tacitly sanctioned what had been done, and because Edward too had been a party to the Cippenham skullduggery: the last act in the long feud with his midland adversary. After Ferrers's release he could bring no immediate action against Edmund because of his supplanter's departure on crusade, and the legal protection that went with it. In 1273, soon after Edmund's return, Ferrers took the law into his own hands by seizing his old castle at Chartley, but he was soon ejected by Edmund's forces. He prepared more effectively for action by seeking help from the powerful Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester. In May 1273 he made a series of agreements with Clare, by which he promised him extensive lands, including the bulk of the Chester inheritance between Ribble and Mersey, in return for Clare's undertaking to maintain his affairs, to grant him 200 librates of land until his restoration, and to try to secure him a reasonable redemption settlement. The legal case to which this scheme was the preliminary began in October 1274, shortly after Edward I's return to England. It turned on Ferrers's plea that he was willing to stand on the terms of the dictum of Kenilworth—seven years' redemption—but that Edmund had refused to countenance this. Edmund responded by producing the Cippenham ‘agreement’ and invoking Ferrers's failure to meet its terms. The counterplea advanced by Ferrers, that the ‘agreement’ was made under duress, while he was in prison, availed nothing, for Edmund was able to retort that the chancellor's presence at the making of the ‘agreement’ gave it the force of record, with full legal validity. Ferrers's case was then dismissed. He found some consolation in 1275, when he brought a successful action for the recovery of his manor of Chartley; though Edmund retained the castle. When he died in 1279 Chartley was all that remained of his inheritance. Foolish though he had been, he had a good case in law, and its failure showed how the interests of the royal family could still take precedence over justice. In his later years Ferrers may have derived more satisfaction from his family life than from his standing as a magnate who had fallen on hard times. His first wife, Mary, died some time between 1266 and 1269, and on 26 June 1269, a month after his release from prison, he married Eleanor, daughter of Humphrey (V) de Bohun (who was killed fighting for Montfort at Evesham), and granddaughter of the earl of Hereford. His earlier marriage had been childless, but with Eleanor he had at least two sons: John de Ferrers, born at Cardiff on 20 June 1271, and Thomas, on whom he settled a small sum between 1274 and 1279. John was to be prominent in the baronial opposition to Edward I in 1297, a stance that must have been linked with his continuing attempts to regain his father's lost inheritance. Between 1269 and 1275 the landless Ferrers spent some time on his mother's dower lands in Northamptonshire, but after 1275 he appears to have resided at Chartley. Towards the end of his life he made a number of grants to the neighbouring Augustinian priory of St Thomas, Stafford, which seems to have replaced Tutbury as the family house. There he was probably buried, as he had certainly intended to be. His widow survived until 1314, engaging in her former husband's great cause by bringing a claim against Edmund for dower in his ancestral lands, but settling eventually for the manor of Godmanchester, Huntingdonshire. In a short lifetime Robert de Ferrers had broken one of the greatest of baronial families by his ill-judged actions and contributed to the rise of another by the conferment of his lands on Edmund, earl of Lancaster. Like his enemies—Edward, the future king, and Simon de Montfort—he was quick to resort to violence, but unlike them he was unable to justify violence by any appeal to principle. Isolated by the pursuit of his own interests, he found himself without a party in a dangerously polarized political world, and, in combination with the ruthlessness of his opponents and his own lack of political intelligence, that was the cause of his downfall. J. R. Maddicott Sources Ann. mon. · The metrical chronicle of Robert of Gloucester, ed. W. A. Wright, 2 vols., Rolls Series, 86 (1887) · R. C. Christie, ed. and trans., Annales Cestrienses, or, Chronicle of the abbey of S. Werburg at Chester, Lancashire and Cheshire RS, 14 (1887) · A. Saltman, ed., Cartulary of Tutbury Priory, HMC, JP 2 (1962) · Chancery records · Paris, Chron. · R. F. Treharne and I. J. Sanders, eds., Documents of the baronial movement of reform and rebellion, 1258–1267 (1973) · P. E. Golob, ‘The Ferrers earls of Derby: a study of the honour of Tutbury, 1066–1279’, PhD diss., U. Cam., 1985 · J. R. Maddicott, Simon de Montfort (1994) · E. F. Jacob, Studies in the period of baronial reform and rebellion, 1258–1267 (1925) Wealth at death £55 p.a.—value of the manor of Chartley © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press J. R. Maddicott, ‘Ferrers, Robert de, sixth earl of Derby (c.1239-1279)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/9366, accessed 24 Sept 2005] Robert de Ferrers (c.1239-1279): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/93668 | |

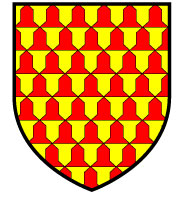

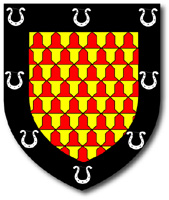

| DNB | Ferrers family (per. c.1240-1445), nobility, were lords of Groby in Leicestershire. The family was descended from Henry de Ferrers who arrived in England from Normandy during the reign of William I, and whose heir, Robert (d. 1139), was created earl of Derby by King Stephen. The Leicestershire branch of the family was established by William [i] Ferrers (c.1240-1287), younger son of William Ferrers, fifth earl of Derby (d. 1254), and Margaret (d. 1281), eldest daughter and coheir of Roger de Quincy, earl of Winchester (d. 1264). In 1251 his father granted William the Essex manors of Fairstead, Stebbing, and Woodham, valued in 1281 at £83 per annum; from his mother he inherited Groby as well as the manor of Newbottle in Northamptonshire and lands in Scotland, while a gift from his elder brother, Robert (d. 1279), of the wapentake of Leyland extended the family's estate into Lancashire. Like Robert, William supported their cousin, Simon de Montfort, during the barons' war but, despite being captured in arms against the king at Northampton in 1264, he received a royal pardon in July 1266. The identity of William's first wife, Anne (d. after February 1272), is uncertain but she may have been a daughter of Sir Hugh Despenser (d. 1265) of Ryhall in Rutland, a fellow partisan of Simon de Montfort. His second wife was Eleanor (d. after May 1326), daughter of Sir Matthew de Lovaine of Little Easton in Essex. After her first husband's death, Eleanor subsequently married Sir William Douglas of Douglas in Scotland (d. 1298/1299) and then Sir William Bagot of Staffordshire (d. 1324). William [i] Ferrers's only known offspring was his son and heir, William [ii] Ferrers, first Lord Ferrers (1272-1325), who was born to Anne on 31 January 1272 at the manor of Yoxall in Staffordshire, where he was also baptized. After his father's death in 1287, William [ii]'s wardship was granted to Nicholas Seagrave the younger for a fine of 100 marks and an annual payment of over £150, an arrangement which ended in March 1293 when William received livery of his lands. By 1295 he had entered royal service as an agent at the court of Duke John (II) of Brabant, but he was drawn more to the military life, serving regularly in the Scottish campaigns of both Edward I and Edward II, and from 1317 as one of the constables of Somerton Castle in Lincolnshire. He was also the first of his family to receive a writ of summons to parliament in 1299 as Lord Ferrers. With his wife, Ellen, possibly a kinswoman of Nicholas Seagrave, William [ii] had a daughter and four sons, including his heir, Henry [i] Ferrers, second Lord Ferrers (c.1303-1343). Henry [i] was arguably the most successful member of his family. Of the six generations of Ferrerses from 1240 to 1445, he alone succeeded to the patrimony as an adult, thereby protecting his inheritance from the hazards of wardship. Furthermore, by February 1331 he had secured in marriage Isabel (1317–1349), posthumous daughter and coheir of Theobald de Verdon, first Lord Verdon (d. 1316), of Alton in Staffordshire [see under Verdon, Theobald de, first Lord Verdon (1248?-1309)], and Elizabeth (d. 1360), sister and coheir of Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester (d. 1314). Despite an earlier division of the Verdon inheritance which had been to Isabel's (and therefore Henry's) disadvantage, by 1335 Henry had possession of his wife's property in Ireland and in seven midland counties stretching between Derbyshire and Gloucestershire. At the same time, he was granted the reversion of his mother-in-law's manors in four midland counties. These manors eventually devolved to Henry's son in 1360. By 1329 Henry had entered the employ of the earl of Lancaster, providing the earl with military assistance at Bedford in January of that year. The following year the earl began paying him an annuity of £100, suggesting that Henry had become a member of the Lancastrian council. Royal service brought additional rewards. Henry first served Edward III, then prince of Wales, in 1325, when he accompanied him to France in the retinue of Henry Beaumont. Thereafter he was summoned to the aborted 1332 expedition to Ireland, participated in the invasion of Scotland later that year, and was appointed keeper of the Channel Islands in 1333. As a member of the council and king's chamberlain, Henry [i] Ferrers became closely involved with the war effort of the late 1330s and early 1340s, negotiating an alliance with the count of Flanders, accompanying the king on his military expeditions, and contracting to raise loans and to act as guarantor for them. For these services he was granted economic privileges including trading concessions in wine (1337), the right to hold weekly markets and annual fairs at Groby, Stebbing, and Woodham (1338), and licences to export wool (1338, 1340). In addition, in 1337 the king granted him a manor in Buckinghamshire and the reversion of two further manors in Derbyshire and Essex to the total value of £160 per annum. These achievements notwithstanding, Henry [i]'s career was brief. In July 1342 he was reported to be ‘sick and weak’, and on 15 September the following year he died at Groby, being buried in the priory at Ulverscroft. He was survived by two sons and two daughters, and by his wife, Isabel, who died on 25 July 1349, probably of plague, aged thirty-two years. Henry [i] Ferrers was succeeded by his ten-year-old son, William [iii] Ferrers, third Lord Ferrers (1333-1371), who was born on 28 February 1333 at Newbold Verdon, and baptized there on the same day in the church of St Mary. In 1345 an income of £50 was set aside for his sustenance, but his lands were temporarily divided between the queen and Prince Edward. The arrival of the black death also had a damaging effect upon the family's economic well-being. By September 1349 on the manor of Hethe in Oxfordshire twenty-one of the twenty-seven villeins had died, leaving their lands untilled, while the hundred of Bradford in Shropshire had more than halved in value by 1351. The need for economic reorganization, therefore, probably lay behind William's exchange with the earl of March of land in Shropshire for land in Buckinghamshire in 1358, and his decision in 1364 to sell most of his Irish estate. No doubt, too, the prospect of economic gain played some part in his decision to serve in France in 1355, at Poitiers in 1356, in the duke of Lancaster's invasion of France in 1359–60, and again in 1369. From his marriage to Margaret (d. before 1368), sister and in her issue coheir of William Ufford, earl of Suffolk (d. 1382), William [iii] had a son and two daughters. His second marriage was to Margaret (d. 1375), daughter of Henry Percy, second Lord Percy (1301-1352), and was childless. In his will dated 1 June 1368, William requested burial in the church at Ulverscroft Priory. He died at Stebbing on 8 January 1371, leaving Henry [ii] Ferrers, fourth Baron Ferrers of Groby (1356-1388), as his heir. Henry had been born in Tilty Abbey in Essex on 6 February 1356. As a minor he fell prey to the fraudulent schemes of his father's feoffees, who attempted to deprive him of manors in Essex and Warwickshire. During the 1380s he regularly served on Leicestershire commissions of the peace, array, and oyer and terminer. He also accompanied Richard II to Scotland in 1385. He died at the age of thirty-two on 3 February 1388, being survived by his wife, Joan Hoo (d. 1394) of Luton Hoo, and his heir, William [iv] Ferrers, fifth Baron Ferrers of Groby (1372-1445), who had been born at Hoo in Bedfordshire on 25 April 1372. Within months of his father's death, William's marriage was sold to Roger Clifford, fifth Baron Clifford (1333-1389), whose daughter, Philippa, became his first wife. Later wives were Margaret Montagu (d. before October 1416), daughter of John Montagu, third earl of Salisbury (c.1350-1400), and Elizabeth (d. before 1445), daughter of Sir Robert Standisshe of Lancashire. Upon reaching his majority in 1394, William [iv] Ferrers accompanied Richard II to Ireland but his political affiliations were flexible; in 1401 he was among the lords who condemned Thomas and John Holland as traitors. Indeed, throughout his life William devoted his energies more to county administration rather than national politics, serving as JP and on an array of commissions in Leicestershire until his death at Woodham Ferrers, Essex, on 18 May 1445. He bequeathed his body for burial in Ulverscroft Priory. William [iv]'s declared income in 1436 was £666, but his younger son, Thomas, accounted for an additional £100. Although Thomas was William's heir male, Groby, along with the lordship of Ferrers, passed to a granddaughter, Elizabeth, daughter and heir of William's elder son, Henry [iii] (d. 1425). Through her marriage in 1426 to Edward Grey (d. 1457), the lordship was ultimately conveyed to the Grey family. The Ferrers family arms were gules, seven mascles voided or. All the Ferrers lords of Groby from William [ii] onwards were regularly summoned to parliament, enabling them to maintain their status as peers. The family's problem was less one of fertility than of mortality. Most of the Ferrers males were short-lived, leading not only to a succession of costly minorities but also to a repeated failure to develop lucrative political careers. Similarly, the early death in 1425 of William [iv] Ferrers's elder son, Henry [iii], before he had produced a male heir, led to the family's eventual undoing. Eric Acheson Sources CIPM, vols. 1–16 · Chancery records · W. Stubbs, ed., Chronicles of the reigns of Edward I and Edward II, 2 vols., Rolls Series, 76 (1882–3) · Report on manuscripts in various collections, 8 vols., HMC, 55 (1901–14), vol. 7 · W. Dugdale, The antiquities of Warwickshire illustrated (1656), vol. 2 · T. D. Hardy, Syllabus, in English, of the documents relating to England and other kingdoms contained in the collection known as ‘Rymer's Foedera’, 3 vols., PRO, 76 (1869–85) · Inquisitions and assessments relating to feudal aids, 6 vols., PRO (1899–1921) · J. Nichols, The history and antiquities of the county of Leicester, 4 vols. (1795–1815) · S. Shaw, The history and antiquities of Staffordshire, 2 vols. (1798–1801) · VCH Rutland · VCH Staffordshire · VCH Leicestershire · Exchequer, King's Remembrancer, subsidy rolls, PRO, E179 · H. L. Gray, ‘Incomes from land in England in 1436’, EngHR, 49 (1934), 607–39 · GEC, Peerage, 5.340–58 Wealth at death income of £666 in 1436; plus income of £100 for son; William [iv] Ferrers: Gray, ‘Incomes’; PRO, E179/192/59 © Oxford University Press 2004–5 All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press Eric Acheson, ‘Ferrers family (per. c.1240-1445)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/54521, accessed 24 Sept 2005] Ferrers family (per. c.1240-1445): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54521 William Ferrers [i] (c.1240-1287): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/65399 William Ferrers [ii] , first Lord Ferrers (1272-1325): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/65400 Henry Ferrers [i] , second Lord Ferrers (c.1303-1343): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/65401 William Ferrers [iii] , third Lord Ferrers (1333-1371): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/65402 Henry Ferrers [ii] , fourth Baron Ferrers of Groby (1356-1388): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/65403 William Ferrers [iv] , fifth Baron Ferrers of Groby (1372-1445): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/654048 | |

| Arms* | 1254 | Sealed: Vairy2 |

| Event-Misc | 15 April 1254 | Wardship of his lands was granted to Prince Edward.9 |

| Note* | 1263 | At the outbreak of the Barons' War, he joined the Barons and seized three of Prince Edward's castles.3 |

| Protection* | 13 February 1263 | overseas2 |

| Event-Misc | 29 February 1263/64 | He captured Worcester and destroyed the town and Jewry3 |

| Event-Misc* | 24 August 1264 | K. has certain arguous business touching him, and commands him to give full credence to Simon, E. of Leicester, bringing messages from K.2 |